| |

FIG PUBLICATION NO. 44

Improving Slum Conditions through Innovative

Financing

FIG/UN-HABITAT Seminar

Stockholm, Sweden, 16–17 June 2008

|

© Klas Björkhagen |

© Klas Björkhagen |

Contents

Foreword

List of Acronyms

Seminar Information and Proceedings

Key Web Sites

Acknowledgements

Introduction

About the Seminar Organisers

DAY 1– LAND USE MANAGEMENT AND PROPERTY

RIGHTS

Opening Ceremony

Mr. Svante Astermo, Chair, Local Organising Committee

Professor Stig Enemark, President of FIG

Mr. Andreas Carlgren, Minister for the Environment,

Sweden

Keynote Address

Excerpts from Keynote Address

Mrs. Anna Tibaijuka, Under Secretary General and Executive Director, UN-HABITAT

Sustainable Urban Development and the

Millennium Development Goals

Environment and Climate: The Role and Importance of

Property and Land Administration Institutions in Society

– Mr. Andreas Carlgren, Minister for the Environment, Sweden

Legal Empowerment in a Globalizing World

– Mr. Ashraf Ghani, Institute for State Effectiveness and Chair of the Working

Group on Property Rights of Legal Empowerment

Partnership between FIG and the UN Agencies in Support

of the Millennium Development Goals

– Mr. Stig Enemark, President, FIG

Land Administration and Property Rights – How

to Achieve the Basic and Fundamental Structure?

Land Policies across Geography and Time: An

Overview of Land Policy Issues Based on Lincoln Institute’s Experience in Latin

America

– Lincoln Institute of Land Policy

Analytic Conclusions Regarding Countries in Transition:

Spatial Information Management toward Legalizing Informal Urban Development

– Ms. Chryssy Potsiou, Chair of FIG Commission 3, UN-ECE/Working Party on

Land Administration

Development of Land Administration and Links to the

Financial Markets

– Ms. Dorothy Agote, Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Lands, Kenya

Social and Economic Impacts of Land Titling Programmes in

Urban and Peri-Urban Areas: International Experience and Case Studies of Senegal

and South Africa

– Geoffrey Payne, Geoffrey Payne and Associates, U.K.

Women’s Access to Land and Finance

– Ms. Ayanthi Gurushinge, Country Coordinator, Slum Upgrading Facility, Sri

Lanka

Dialogues: Land Use Management and

Property Rights – Outlining the Roadmap

Group 1 – Southern and Eastern Africa

Group 2 – Asia and the Pacific

Group 3 – West Africa

Group 4 – Central and Eastern Europe

DAY 2 – JUST AND SUSTAINABLE SHELTER FINANCE

SYSTEMS

Land Administration and Finance Systems

Expanding the Outreach of Housing Finance for the

Urban Poor – A Matter of Cooperation Combined with Sufficient and Appropriate

Due Diligence

– Mr. Michael Mutter, Senior Advisor, Slum Upgrading Facility, UN-HABITAT

Channelling the Global Financial Flows for Adequate

and Affordable Housing

– Ms. Renu Karnard, President, International Union for Housing Finance

Land Finance through Land Governance – Expanding the

Discussion of Land Policy during Food Crisis, Climate Change and Rapid

Urbanization

– Mr. Malcolm Childress, Senior Land Administration Specialist, The World Bank

Housing Finance for All – Swedish Engagement in Land

Administration and Housing Finance

– Mr. Dan Ericsson, State Secretary, Ministry of Finance, Sweden

Putting Innovative Systems for Functioning

Finance into Practice

Innovative Structures for Financing Slum Housing

and Infrastructure

– Mr. P. R. Anil Kumar, Head (Microfinance), Emerging Markets, Barclays Bank

PLC

Local Finance Facilities: What They Are, Why They Are

Important, and How They Work

– Ms. Ruth McLeod, Emerging Markets Group Dialogues

Dialogues

Dialogue 1: Land management practices and tools and

links to efficient finance

Dialogue 2: Revisiting planning: Cutting the costs,

involving the rights of the poor and enabling adequate finance

Dialogue 3: Linking the financial sources

Dialogue 4: Expanding the outreach of housing finance

for the urban poor

Special Component on Land and

Gender

Wrap Up and the Way Forward

Orders for printed copies

This publication is a summary report of the seminar “Improving Slum

Conditions through Innovative Financing”, which was jointly organized by

the International Federation of Surveyors, FIG and the United Nations Human

Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT) and took place in Stockholm, Sweden on

16–17 June 2008. This two-day seminar, which was dedicated to adequate and

affordable housing for all, was an integrated part of the FIG Working Week.

The seminar focused on the essential elements of a just and sustainable

provision of adequate shelter, from the twin perspectives of land and finance.

It brought together leading actors from the public, private and non-governmental

sectors working on land and housing finance issues. Within this framework, the

seminar focused on the main issues of access to land, security of tenure and

access to finance. Without security of tenure, the poor are at daily risk of

eviction and, in the longer term, are reluctant to invest in long-term shelter

improvements. Without access to affordable finance, poor people are caught in a

vicious cycle in which affordable housing is inadequate, but adequate housing is

unaffordable.

Surveyors and land professionals play a key role in linking functioning

markets for housing and finance. Therefore FIG is keen to co-operate with

UN-HABITAT in this area as part of the long-term co-operation between the two

organizations. The FIG/UN-HABITAT seminar brought together some of the leading

innovators in the areas of land and finance. The seminar was structured as a

practitioners’ dialogue – communication across professional and institutional

perspectives. A total of eight Dialogues were held. Amongst the core issues

discussed were various forms of individual and collective rights, women’s equal

access to land and finance, spatial planning, security of tenure and innovative

financial instruments. Proceedings of the seminar are available at

www.fig.net/pub/fig2008 and a

dedicated web site for the project at

www.justnsustshelter.org.

This report provides a summary of the presentations that were given to

catalyse the Dialogues, the key issues that emerged in the Dialogues themselves,

and the conclusions reached and directions for the way forward that were put

forth at the seminar’s closing.

The result of the seminar aims to provide a valuable contribution to the IV

World Urban Forum, to be held in Nanjing, China in November 2008. The

publication is a joint effort of FIG and UN-HABITAT and is published in the FIG

Report series.

Stig Enemark

FIG President

|

Anna K. Tibaijuka

Under Secretary General

Executive Director UN-HABITAT |

List of Acronyms

| BRICS |

Brazil, India and China |

| FAO |

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations |

| FIG |

International Federation of Surveyors |

| GLTN |

Global Land Tool Network |

| LFSUS |

Lanka Financial Services for Underserved Settlements |

| MDGs |

Millennium Development Goals |

| MFI |

Microfinance institution |

| NGO |

Non-governmental organization |

| SPARC |

Society for the Promotion of Area Resource Centres |

| STDM |

Social Tenure Domain Model |

| SUF |

Slum Upgrading Facility (within UN-HABITAT) |

| UN-HABITAT |

United Nations Human Settlements Programme |

Seminar Information and Proceedings

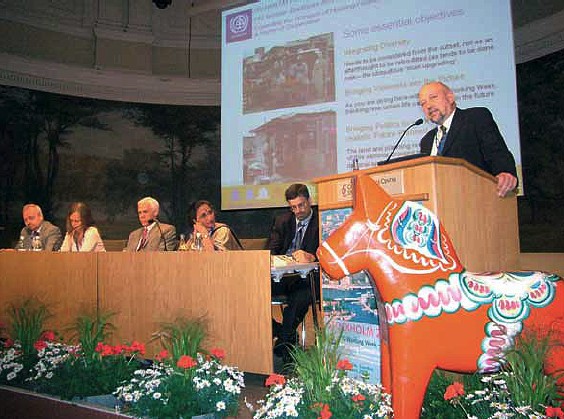

Mr. Michael Mutter, UN-HABITAT making his keynote presentation at the second

plenary session of the FIG/UN-HABITAT seminar. © FIG

The seminar “Improving Slum Conditions through Innovative Financing”

was organised jointly by FIG and UN-HABITAT. It was made possible by the

generous support from Swedish authorities: Lantmäteriet (the National Mapping,

Cadastre and Land Registration Authority of Sweden), the Swedish Government (the

Ministry of the Environment and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs), Swedesurvey

and Statens Bostadskreditnämnd BKN (National Housing Credit Guarantee Board).

We would like to express our thanks to all speakers and participants who

attended the dialogues and contributed to this report. Our special thanks go to

Ms. Ann Jennervik, who was in charge of organising the seminar together

with Mr. Bengt Kjellson and Mr. Lars Magnusson. We also thank Mr.

Brett Shapiro who has been the editor of this report together with Mr.

Szilard Fricska from UN-HABITAT and Professor Stig Enemark from FIG.

As an integrated part of the International Federation of Surveyor’s (FIG)

Working Week, a two-day seminar was dedicated to adequate and affordable

housing for all. The seminar, “Improving Slum Conditions through

Innovative Financing” was jointly organized by FIG and UN-HABITAT and

took place in Stockholm, Sweden on 16–17 June 2008.

The meeting brought together leading actors from the public, private and

non-governmental sectors working on land and housing finance issues. The seminar

focused on the essential elements of a just and sustainable provision of

adequate shelter, from the twin perspectives of land and finance. The role of

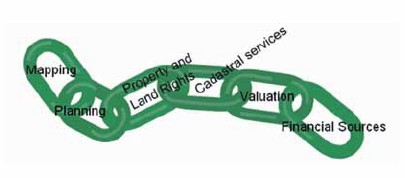

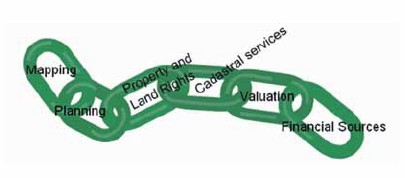

land and finance provision can be conceptualized as the challenge of linking the

various components of “the Land Administration Chain”: mapping; planning;

property and land rights; cadastral services; valuation; financial services (see

figure below).

Linking the Land Administration Chain.

Within this framework, the seminar focused on the main issues of access to land,

security of tenure and access to finance. Without security of tenure, the poor

are at daily risk of eviction and, in the longer term, are reluctant to invest

in long-term shelter improvements. Without access to affordable finance, poor

people are caught in a vicious cycle in which affordable housing is inadequate,

but adequate housing is unaffordable.

The theoretical solution to this dilemma is a well-functioning land and housing

market; however, experts around the world recognize that these same markets are

often dysfunctional, and arguably represent the most consistent bottleneck

undermining long-term city development. Market access is built on transparency,

low transaction costs and good access to reliable property information as well

as property financing. Facilitating efficient land markets and effective

land-use management is therefore critical to sustainable urbanization.

Surveyors play a key role in linking functioning markets for housing and

finance. Support to this aim is being provided, but despite 30 years of efforts,

political commitments and reiterated priority to the issue, little has been

achieved. Building up the key institutions that can manage the public systems

providing key public goods is at best a slow process. The vested interests of a

wide variety of stakeholders conspire to maintain the status quo.

There are signs of progress, however, and the FIG/UN-HABITAT seminar brought

together some of the leading innovators in the areas of land and finance. The

seminar was structured as a practitioners’ dialogue – communication across

professional and institutional perspectives. A total of eight Dialogues were

held. Each set of Dialogues was prepared through sharing inputs at the

interactive website

www.justnsustshelter.org and through the introductory presentations at the

Plenary and Presentation sessions. Amongst the core issues discussed were

various forms of individual and collective rights, women’s equal access to land

and finance, spatial planning, security of tenure and innovative financial

instruments.

The seminar aims to provide a valuable contribution to the next World Urban

Forum, to be held in Nanjing, China in November 2008.

This report provides a summary of the presentations that were given to catalyze

the Dialogues, the key issues that emerged in the Dialogues themselves, and the

conclusions reached and directions for the way forward that were put forth at

the seminar’s closing.

About the Seminar Organisers

International Federation of Surveyors (FIG)

The International Federation of Surveyors, FIG, is an international,

non-government organisation (NGO) whose purpose is to support international

collaboration for the progress of surveying in all fields and applications. FIG

aims to mobilize the next generation of land professionals to continue to

develop innovative solutions to address global inequality in access to land and

security of tenure. FIG’s annual “Working Week” took place in Stockholm, Sweden

and was the biggest Working Week ever held, with 950 participants from 90

nations attending the event and exhibition. In addition to the plenary sessions,

there were over 70 technical sessions, with almost 350 presentations and

technical tours. A strong attraction was the two-day joint FIG/UN-HABITAT

seminar on “Improving Slum Conditions through Innovative Financing,” which was

an integral part of the entire Working Week. FIG is strongly committed to the

Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and to supporting the work of the Global

Land Tool Network (GLTN), whose aim is to contribute to poverty alleviation and

the MDGs through land reform, improved land management and security of tenure.

United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT)

UN-HABITAT is the United Nations agency for human settlements. It is mandated by

the UN General Assembly to promote socially and environmentally sustainable

towns and cities with the goal of providing adequate shelter for all. Within

this mandate, the Slum Upgrading Facility (SUF) provides global assistance for

the design and implementation of locally produced ‘bankable housing projects’ so

that groups of low income residents and their local authorities can attract

domestic commercial finance as a significant part of the funding of their

sustainable neighbourhood slum upgrading and low-income housing projects on a

community-led repayment scheme basis. With respect to land issues, UN-HABITAT

also hosts the Secretariat for the GLTN. GLTN partners have identified 18 key

land tools to deal with poverty and land issues at the country level across all

regions. One of GLTN’s work areas is the nexus between intermediate forms of

tenure and access to housing finance for the poor.

Day 1 – Land Use Management and Property

Rights

The theme during the first day was Land Use Management and Property

Rights. Land Administration is a term used to describe all the processes

connected to a functioning property system. This includes land management,

planning and monitoring land use, the creation and keeping of cadastre, the

establishment, recording and protection of different kinds of property rights

and the securing of mortgage rights in order to make capital available to

property owners or leaseholders. Land administration systems look different in

different countries and regions and are evolving in different ways. This is due

to the political circumstances, cultural and legal traditions and economic

conditions that exist in each particular setting.

The Opening Ceremony featured the symbolic tying of a ribbon, representing

the continuity between the current and future generation of land professionals.

Speakers at the opening ceremony included the following:

Mr. Svante Astermo, Chair, Local Organising

Committee

Mr. Astermo welcomed all of the participants, mentioning that the 950

participants from 90 countries represented an all-time high for the FIG Working

Week. He was particularly pleased to see the presence of so many students, given

that they are the key to “integrating generations” – creating the bridge between

countries, cultures and ages.

Mr. Enemark reiterated FIG’s support of the concept of integrating

generations, acknowledging the many students and young surveyors present who

represent the future. He also mentioned a full-page article that appeared in one

of the major Swedish daily newspapers in which surveyors were called upon to

address the problems of the slums, and stated that FIG is becoming a major

partner in achieving sustainable development. At the same time, there is a need

to better understand the very key role that the profession plays in sustainable

development at the national and local levels. The work of surveyors forms a kind

of backbone to society and is a key component to the achievement of the MDGs.

The global development agenda is about eradication of poverty in all its forms.

Property is not only an economic asset, he stressed, but secure property rights

also provide a sense of identity and belonging that goes far beyond economics,

and underpins democracy and human freedom. Land surveys have a key role to play

in developing pro-poor systems. Professor Enemark then introduced the concept of

land governance, which is the governmental side of managing physical space for

power, wealth and human well-being. The key challenges of the new millennium are

related to climate change, urban growth, environmental degradation, natural

disasters and food shortages. All of these challenges relate to the governance

and management of land. Thus, land governance and management are going to be

important subjects for surveyors, issues which will require new models to

predict and address changes, and land administration systems that can manage the

core functions of land value, land use and land development.

Mr. Andreas Carlgren, Minister for the

Environment, Sweden

Mr. Carlgren emphasized that land professionals “have such an important key

role to play, to combat environmental threats, to combat poverty and slums and

to support the development of this globe and its cities.” He then tied two

ribbons together as a symbol of integrating generations.

Kibera, Nairobi. © Stig Enemark

Excerpts from Keynote Address

– Mrs. Anna Tibaijuka, Under Secretary General and Executive Director,

UN-HABITAT

|

© FIG |

“FIG and UN-HABITAT have a shared history that goes back over two

decades. I am pleased to see that this meeting is taking place when the

Swedish Association of Chartered Surveyors is celebrating its 100th

anniversary. I am also pleased to be in Stockholm because UN-HABITAT has

a history here dating back to 1972 when the concept of sustainable

development was born… The theme of the seminar, Integrating

Generations, highlights the need to attract new generation of young

surveyors and new capacities to address to new priorities… |

I would like to present two critical issues that we see shaping the

global debate on development. They are sustainable urbanization and climate

change, and they are interlinked. I would also like to reflect on the role

that surveyors and land specialists can play…

We are becoming more urban, and this will not change. People move because

they expect to have a better life. It is the expectation that pushes them,

and the prospect keeps them there. The challenge is to guide the

urbanization process. Ninety-five percent is taking place in cities least

equipped to deal with it, in African and in Asia. We are witnessing

urbanization of poverty. Today there are an estimated 1 billion slum

dwellers, and this could double by 2030. A report published by UN-HABITAT in

2006–2007 confirms that slum dwellers are more likely to have less education

and fewer employment opportunities, and suffer malnutrition more than any

other segment of the population. Living in cities does not translate into a

better life. How is the international community responding? UN-HABITAT

conducted an exercise in 2005 to determine the resources required. Our

estimate showed that US$ 300 billion would be required over a 15-year period

if we wanted to put the slum challenge behind us. While these exercises are

nothing new, the uniqueness of this exercise was in its recognition that the

urban poor, when properly enabled and empowered, are able to mobilize 85

percent of the resources required…

…We know that an aid-based approach is not enough. We need to think outside

the box, we need to think in terms of changing the rules of the game that

prevent the majority of the urban population in developing countries from

growing out of poverty. …Let me outline some of the challenges of slum dwellers

from the land perspective. Only 20 percent of land parcels in the world are

registered, while most poor people live under customary or informal tenure

systems. Only 2 percent of land is registered in women’s name, and women are

frequently at risk of losing their land rights upon the death of their spouses.

Land titling rarely meets the needs of thepoor due to the costs of adjudication,

high technical standards, expensive registration and transfer fees, and literacy

requirements. Planning and zoning standards are similarly inappropriate and

unaffordable. In short, the very legal system that should protect and empower

the poor more often fails them. This is one of the most important findings of

the Commission for the Legal Empowerment of the Poor and I would encourage you

all to read the Commission’s report [see

http://www.undp.org/legalempowerment/]…

As in the world of land, slum dwellers are often systematically excluded from

the so-called ‘formal’ system of housing finance, in particular, mortgage

finance…

Banks are constrained by the very systems of credit risk analysis they use:

financial, legal and technical. Their financial analysis is biased towards

people with bank accounts, formal sector jobs and a proven credit history. In

their legal analysis, financial institutions look for legally recognized

evidence of ownership and the possibility of repossessing the asset through the

courts in case of default. And, from their technical analysis, they will look

for proof of a building permit and conformance to zoning regulations. From all

three risk analysis perspectives, the poor fail the test of the formal credit

markets…

Micro-finance institutions do better for the poor. They will provide small

loans. They will not demand land as collateral. However, the loans they give are

not housing loans. They are housing loans disguised as consumption or as

business loans. This may be a stop-gap measure, but it struggles to meet the

full demand for housing loans…

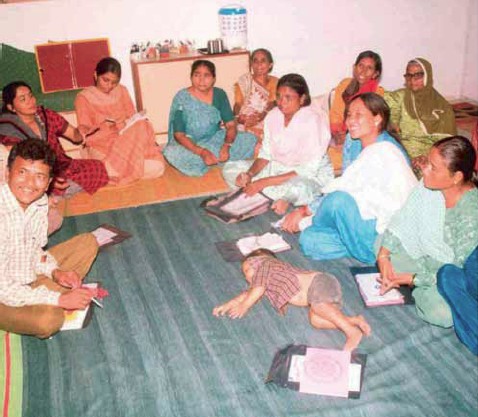

There are signs of hope in the area of housing finance. In particular, group

savings and cooperatives represent promising solutions. Savings schemes are

established amongst groups of slums dwellers – mainly by women – who wish to

improve their living conditions through a specific project. They establish

themselves as a legal entity, which enables them to consider taking a loan. The

size of the loan will be determined by their ability to repay. This becomes the

basis for designing a bankable project. Financial institutions become interested

because the loan size is large and the transaction costs are low. From this

model, and others that are out there, it is clear that the poor can provide

their own housing solutions…

But housing finance is only one piece in a much larger challenge of

sustainable urbanization. Reforms are required on a number of fronts, including:

land market regulation, shifting to more strategic urban planning, adopting

pro-poor building regulations, improving land-based tax collection to create

municipal revenue, making budgeting more participatory and accountable, and

creating the foundations for sustainable investments in infrastructure and

service delivery…

What is the role of surveyors and land professionals in the creation of a

sustainable urbanization paradigm? I would like to highlight six critical areas:

- Better information for better decision making and planning

- Disaster risk reduction tools

- New land administration tools appropriate for developing countries

- Strengthened capacity in land valuation and land value capture

- A new generation of surveying and volunteerism, to strengthen the

capacity of

land professionals in the South

- Good land governance; that is, the process of managing competing

interests in

land in a way that promotes sustainable urbanization.

In this regard, I would like to highlight the important role being played by

the GLTN, and its partners in promoting innovative solutions to realize secure

land rights for all. FIG and UN-HABITAT have worked closely together under the

GLTN umbrella to make this seminar a reality…

I hope this meeting will help set a new agenda for sustainable development

and climate change.

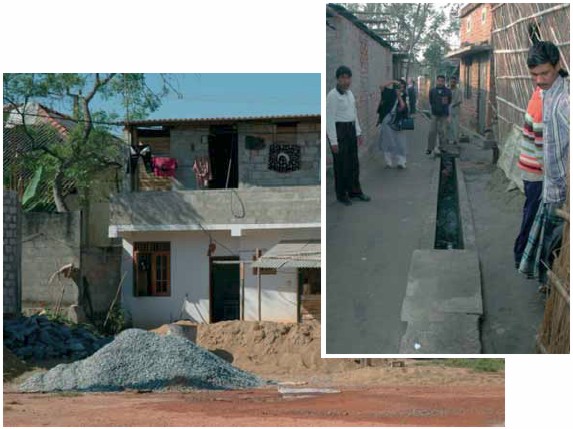

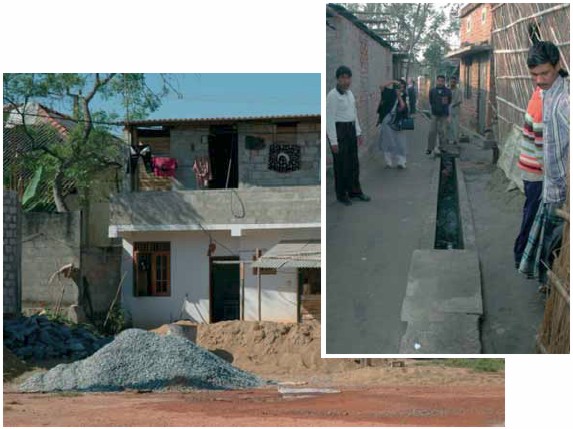

Colombo, Sri Lanka. © Ayanthi Gurushinge

Sustainable Urban Development and

the Millennium Development Goals

Environment and Climate: The Role and Importance

of Property and Land Administration Institutions in Society

– Mr. Andreas Carlgren, Minister for the Environment, Sweden

|

© FIG |

Mr. Carlgren stated that one half of the earth’s systems are in the

process of being destroyed and that there are serious risks and

consequences for combating poverty and access to clean water, the

effects of which can be seen in droughts, floods and outbreaks of

environmentally related diseases. He recounted a meeting of

environmental ministers from 30 countries from around the world that

took place in the north of Sweden. The participants were standing close

to the largest river in the north of Sweden and were drinking from its

water and talking about the destruction of rain forests in Brazil and

the risk of flooding of hundreds of islands. As they stood there, they

experienced the connections and the distances shrinking. The

participants felt that the world is closely connected, both in terms of

threats and hopes. |

Mr. Carlgren urged everyone to commit themselves to combat climate change and

to strive towards a global agreement next year in Copenhagen in 2009, the year

in which Sweden will hold the presidency of the European Union. He affirmed that

Sweden is prepared to reach a global agreement and knows that the world will

undergo an enormous shift towards sustainable development – simply because it

must.

Mr. Carlgren then spoke about the scale of urbanization taking place in

developing countries, with 18 million people moving from the country to cities

each year in China alone. Each day the global urban population grows by 180,000.

A major part of all construction will take place in the large developing

countries. How these cities are built will have an enormous impact on the

environment and quality of life, but also on the long-term possibilities for

tacking climate change. Eighty percent of greenhouse gas emissions originate

from urban areas. But it is possible to change urban development and have

flourishing economies at the same time. If planned and managed correctly, cities

hold possible solutions for many of these problems. For example through

infrastructure, energy and transport solutions, sustainable urban development

cannot only boost the economy and quality of life, but also be part of a global

zero-carbon-producing planet.

Mr. Carlgren described how in Sweden 40 percent of energy supplied is from

renewable sources, and will increase to almost 50 percent soon. Sweden has also

reduced its carbon emissions in absolute terms by 9 percent since 1990, and

without creating problems for the economy. In fact, the economy has increase by

44 percent. Therefore, emissions and economic growth can be delinked. He

mentioned different measures and technologies that have been important,

including economic instruments such as carbon tax, district heating and cooling

systems, and expansion of wind power.

He emphasized that this conference is extremely important in order to

exchange experiences and new solutions. The availability and dissemination of

knowledge and information are vital for combating climate change and adapting

society. Satellite imagery data bases and other reliable cartographical data are

essential, as well as action programmes to analyse the risks of natural

disasters. Guaranteed rights of ownership are also essential for sustainable

development.

Legal Empowerment in a Globalizing World

– Mr. Ashraf Ghani, Institute for State Effectiveness and Chair of the

Working Group on Property Rights of Legal Empowerment

|

© FIG |

Mr. Ghani began by stating that one third of the world’s poor – one

billion people – live without any legal protection of their assets, and

that poverty is a result of the failure of public policies and markets.

In fact, in many countries the laws, institutions and policies are a

barrier to prosperity. He highlighted the recently launched report of

the Commission for the Legal Empowerment of the Poor, “Making the Law

Work for Everyone.” Legal empowerment, he stated, is the process through

which the poor become protected and are enabled to use the law to

advance their rights and interests. He then described the Commission’s

four-pillar approach to empowering the poor: access to justice and the

rule of law; property rights; labour rights; and business rights. The

four key building blocks are interdependent, and when one or more of

them is missing, dysfunctionality results. He then highlighted four

types of dysfunctionalities: misalignment of social practices and legal

provision; misuse of rules governing property; lack of access to

information and justice; and misuse of eminent domain. |

To arrive at solutions, he emphasized that it was not enough to rely on

aid-based approaches.Rather, it is critical to look at globalization and

inclusion. Globalization is of human making but not of human design. Most of the

world feels dislocated by the process of globalization. There are five

challenges for harnessing globalization:

- Build functioning state and markets in the 40–60 states that are the

weak links of the international system.

- Tailor strategies and partnerships to the BRICS (countries like Brazil,

India and China) and other emerging countries.

- Bring corporations into a global development compact.

- Rethink relations between regional and international security as well as

political organizations.

- Invest in national, regional and international leadership and

management.

Governance needs to re-framed, he stated, as network governance. The task is

to bring states, markets, corporations, civil society and international

organizations together. In the next 25 years, US$ 42–44 trillion will be

invested in global infrastructure. These investments make global economic

integration possible, but could also have severe negative consequences. Getting

the design right is critical. Creating liveable cities is critical for the

agenda of inclusive globalization. But creativity and imagination need

collaboration among many actors. Information, knowledge and wisdom need to be

brought together in harmony.

Mr. Ghani concluded by quoting a Native American saying: “We do not

inherit the earth from our ancestors, we borrow it from our children.”

Hyderabad, India. © Stig Enemark

Partnership between FIG and the UN Agencies in

Support of the Millennium Development Goals

– Mr. Stig Enemark, President, FIG

|

© FIG |

Mr. Enemark spoke first about the land management paradigm, which

includes all activities associated with the management of land and

natural resources that are required to fulfil political objectives and

achieve sustainable development. These include the land policy

framework, land administration functions, land information

infrastructures and the country context, all of which feed into the land

administration system and its impact on sustainable development. Land

administration systems are the basis for conceptualizing rights,

responsibilities and restrictions – the “three Rs” – related to

property. |

A good property system is one in which people can participate in the land

market, make transactions and have access to registration. The infrastructure

supporting transactions must be simple, quick, affordable and free of

corruption. Moreover, the system must provide safety for housing and business,

as well as for capital formation. Land governance and management is a core area

for surveyors and will require:

- High level geodesy models to predict change

- Modern surveying and mapping tools

- Spatial data infrastructures to support decision making on the

environment

- Secure tenure systems

- Sustainable systems for land valuation, land use management and land

development

- Systems for transparency and good governance.

Mr. Enemark went on to speak about partnership, which is the eighth MDG and

can serve as the link that drives development. He emphasized FIG’s close

collaboration with UN-HABITAT, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the

United Nations (FAO), GTLN and the World Bank.

He concluded his presentation by emphasizing the role of FIG in terms of

professional, institutional and global development.

Land Administration and Property Rights –

How to Achieve the Basic and Fundamental Structure?

The afternoon started with introductory presentations on land administration

and property rights all over the world. The presentations covered lessons

learned from various regions: Latin America, European countries in transition to

an open and common market, and Sub-Saharan Africa. Special emphasis was put on

the importance of women’s equal access to land and finance.

Bukit Duri, Jakarta, Indonesia. © Suzi Mutter

Land Policies across Geography and Time: An

Overview of Land Policy Issues Based on Lincoln Institute’s Experience in Latin

America

– Lincoln Institute of Land Policy

The presentation was given by Ann Jennervik, Senior Expert Sustainable

Development, ee&sd, and was based on the first chapter of the Lincoln Institute

book entitled Urban Perspectives, an overview of critical land policy issues

based on the Institute’s experiences in Latin America. Ms. Jennervik summarized

five major points that came out of the study:

- Constraints on policy implementation. Most countries in Latin

America share poor performance when it comes to recovery of publicly

generated land value increments, the delivery of urban infrastructure and

services, the provision of housing alternatives for the urban poor, and

appropriate land taxation. In addition, there is a strong legacy of powerful

landowning interests that influence land policies to their own benefit.

- Unavailable or untapped resources. Urban land is still viewed as

an asset rather than as a taxable base to generate needed resources for the

broader community. Management of existing resources is often characterized

by a lack of operational capacity or unscrupulous behavior on the part of

authorities. Despite the aim to mobilize publicly created land value

increments, the overall balance still leans toward compensation given to

private landowners.

- Lack of information or capacity to use it. Often information

exists, but not the capacity to find, organize and interpret it. Moreover,

public officials are often unable or unwilling to assimilate and translate

information into operational results.

- Lack of dialogue between urban planners and public finance officials.

Planners tend to be concerned with the quality of the constructed

environment, while fiscal officials are seeking to maximize public revenues.

This is reflected in planners often overlooking how projects should be

financed and how urban forms affect the tax base, or the impacts of tax

collection practices on land uses.

- Discontinuity in programme implementation. Even the most popular

or successful programmes can be disrupted, derailed and ultimately

terminated by political and administrative discontinuities. Expectations

about the permanence of the rules of the game is a major component affecting

how the private sector acts.

Ms. Jennervik concluded by emphasizing the clear evidence that sharing

experiences and lessons learned advances progress. This information should be

used to qualify a broader range of stakeholders capable of not only implementing

better land policies, but also demanding policy responses from public agencies.

Land policy should transcend party politics and promote political plurality and

diversity.

Analytic Conclusions Regarding Countries in

Transition: Spatial Information Management toward Legalizing Informal Urban

Development

– Ms. Chryssy Potsiou, Chair of FIG Commission 3, UN-ECE/Working Party on

Land Administration

Ms. Potsiou opened her presentation by stating that rapid population

increases often lead to unplanned or informal development. Fifty percent of the

world’s population lives in the cities, and one out of three city residents

lives in inadequate housing. The world’s slum population is expected to reach

1.4 billion by 2020. It is a human right that people are free to choose where

they live. However, it is a matter of good governance to achieve sustainable

urban growth.

She went on to describe land policy and the four major land administration

functions – land tenure, land value, land use and land development –

highlighting the lack of an integrated approach. In many countries there is a

tendency to separate land tenure rights from land use rights. In addition,

planning and land use control are not linked with land values and the operation

of the land market. This may be compounded by poor management procedures that

fail to deliver required services. Informal, unplanned, illegal, unauthorized or

random urban development is a major issue in many countries. There is no clear

common definition of what constitutes an informal settlement. The most important

factors for characterizing an area as such are land tenure, quality and size of

construction, access to services and land-use zoning. She gave examples of

informal settlements from Serbia, Montenegro, Albania, Georgia, Greece, Italy,

Croatia, Turkey, etc. and listed many reasons for their establishment,

including: historic, political, social and economic conditions leading to

urbanization; population fluxes as a result of armed conflicts and natural

disasters; lack of spatial information and planning; unrealistic zoning

regulations; marginalization, poverty and lack of financing mechanisms for

affordable housing; inconsistent and complex legislation; excessive bureaucracy

regarding land development and building permits; and local estate taxes. She

concluded her presentation by describing four conditions to reduce the

phenomenon:

- Registration of property rights of both formal and informal construction

is important for proper decision making.

- Land-use planning is the task of government at appropriate levels.

Citizen participation should be part of the planning process.

- Coordination among land-related agencies should be strengthened, and the

private sector should play a role.

- Municipalities should be independent from government in terms of

funding. Real property taxes should be collected and reinvested locally,

while citizens should recognize their responsibility to contribute to the

cost of land improvement and the provision of services.

Informal settlements in Tirana, Albania. © Doris Aldoni

Development of Land Administration and Links to

the Financial Markets

– Ms. Dorothy Agote, Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Lands, Kenya

Ms. Agote began by recalling the thousands of Kenyans who were displaced by

recent post-election violence. She stated that the main cause of their

displacement, and of the violence, was land. This emphasizes the importance of

governance issues with respect to land. In Kenya, the development agenda has

always avoided a serious engagement with land issues. Slums are a major social

and economic concern in Kenya, and a major limiting factor in development. The

majority of people in slums are unable to meet their basic requirements. And 60

percent of them are absolutely poor. The influx of youth has compounded the slum

situation. Urban areas are experiencing increased demand for decent housing. A

Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper was prepared that included slum upgrading

programmes. Beneficiaries should be involved in the design and implementation of

such programmes, as they can provide data and detailed insights into their

problems.

Slum dwellers live outside the rule of law and basic legal protection, and

the government is now seeking to promote tenure security issues through a number

of initiatives, including the land policy formulation process, the adoption of

eviction guidelines, land control boards, and land dispute tribunals – all

geared to helping slum dwellers have a basic level of legal protection.

Ms. Agote went on to speak about land administration and links to financial

markets, and how in Kenya the lack of security of tenure weakens the link. This

is a major challenge and impacts on other ways of using land as collateral. The

design of land administration is crucial. Too often a centralized land

administration system is complex, thus compounding the problem of access to

financial markets. And Kenya is a clear example of that problem: systems are old

and do not respond to current needs. The Kenya draft land policy recognizes

this, and the principles for guidelines have been recommended in the draft

policy. In addition, there is a need for gender equality, a lack of which often

blocks women’s access to financial markets. Women are not considered fit to

inherit and hold property. One key is the formulation of the national land

policy, ensuring that it is harmonized, has simple and cost-effective land laws,

and takes into consideration customary and common resource land.

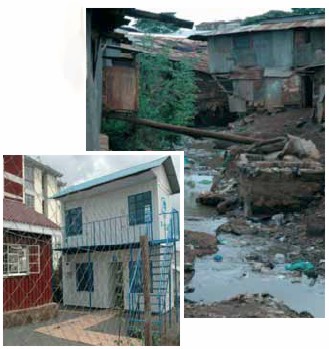

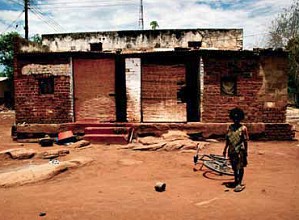

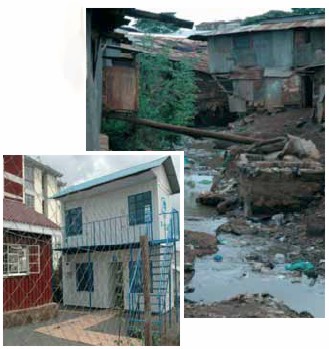

Conditions in Kibera, Nairobi – home to 800,000 slum dwellers, 40% of the

population and the workforce that keeps the city economy going and competitive –

has almost no sanitation, hence an environment of flying toilets, blocked

gulleys and broken culverts – appalling conditions. © Michael Mutter

Social and Economic Impacts of Land Titling Programmes

in Urban and Peri-Urban Areas: International Experience and Case Studies of

Senegal and South Africa

– Geoffrey Payne, Geoffrey Payne and Associates, U.K.

Mr. Payne described a research project that was undertaken in 2006 and 2007

to understand the impacts of land titling programmes in Senegal and South

Africa. A major research issue was whether titling stimulates investment in

housing and property development. One important finding from the study is that

the perception of security is often more important than the titles themselves,

and the promise of titles is more important than their actual delivery. In

addition, titling is not the only means of encouraging investment in housing and

land. Other factors include finances, the location of the settlements, the

provision of services and other upgrading measures, and the regulatory

framework.

In many cases, titling has not increased revenues and in some cases it has

reduced them. In addition, charges are based on land prices and are restricted

by the ability to pay, or can result in forced distress sales. The charges set

according to affordability levels may cost more to collect than is justified.

They may also discourage households from completing the tenure formalization

process. In this regard, action needs to be taken to facilitate transparent land

and housing markets that enjoy social legitimacy.

Mr. Payne offered a number of general conclusions:

- Titling programmes undertaken primarily for economic reasons (e.g. to

secure investment) have failed to realize social objectives (securing land

rights of the the poor).

- Titling programmes undertaken for primarily social reasons also appear

to be of limited value, sometimes contributing to gentrification in urban

areas.

- Programmes undertaken on a small scale contribute to land market

distortion. On the other hand, programmes undertaken on a large scale may

over-burden land administration agencies.

- Top-down, or outside-in, programmes do not work.

- Social legitimacy is vital, as is building on what works in an

incremental way.

Mr. Payne concluded by describing a number of policy implications: assess the

number and quality of land records required and the capacity of the

administrative system; introduce/expand innovative finance mechanisms to provide

credit to the poor; review/relax the regulatory framework for managing urban

land and housing markets; introduce/expand multi-stakeholder partnerships;

encourage a range of tenure options so all groups have a choice; and avoid

“quick fixes”.

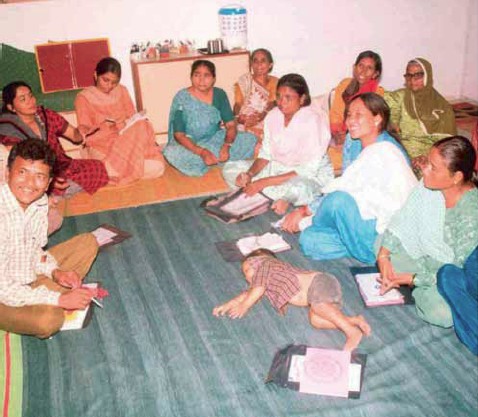

Women’s Savings Group exchange meeting – East Africa meets West

and South Africa. © Michael Mutter

Women’s Access to Land and Finance

– Ms. Ayanthi Gurushinge, Country Coordinator, Slum Upgrading Facility, Sri

Lanka

Ms. Gurushinge began by explaining that women’s land rights are extremely

important, since women’s secure access to land can lead to improved family

welfare and women’s empowerment. There are four main barriers to women’s rights

to land and finance: cultural or legal impediments to acquiring land through

markets, inheritance or transfer; barriers created by intra-household customs

and practices related to marriage; discriminatory policies at the central or

local government level; and poorly drafted laws and regulations governing land

and property rights. She described the three types of land laws in Sri Lanka and

the fact that the laws are not applied consistently or coherently. In Sri Lanka,

the “head of household” concept is more of an administrative term than a legal

one, and the household head is presumed to be the male. This had a major impact

on women during the tsunami: in many cases, even if women had owned property

before the tsunami, all houses were given to the “head of household,” which

excluded them.

Ms. Gurushinge described the Lanka Financial Services for Underserved

Settlements (LFSUS), a not-for profit company that mobilizes resources for

country-wide slum upgrading activities through public-private partnership,

promotes the viability of lending to low-income groups, and provides guarantees

to banks to encourage lending for settlement upgrading. The LFSUS has been

established with the support of SUF, which seeks to develop bankable projects

that promote affordable housing for low-income households, the upgrading of

slums, and the provision of urban infrastructures in cities of the developing

world. She highlighted that housing finance needs to be community-based and

simple (minimal paper work, minimal collateral requirements, flexibility in

repayment, incremental housing financing, etc.). She then presented a list of

strategies to develop women’s access to finance:

- Create housing finance systems that are demand-driven.

- Do not restrict finance mechanisms to housing alone.

- Consider using subsidies as tools to facilitate access to finance.

- Include community savings as part of housing finance.

- Maintain flexibility in loan size and purpose.

- Involve people in every stage of planning a housing finance strategy.

- Minimize rules and procedures and maximize flexibility.

- Explore innovative, community-based ways to provide loan security.

In Sri Lanka, the “head of the household” concept is more an administrative term

than a legal term and is commonly understood to be the man. © Ayanthi Gurushinge

Dialogues: Land Use Management and

Property Rights – Outlining the Roadmap

Four parallel regional “Dialogues to outline the Roadmap to Functioning

Land Use Management for All” were held, focusing on an exchange of

experiences from different parts of the world. The objective was to address

issues specific to each region, as well as commonalities, success stories and

failures, in order to gain a better understanding of how land administration

systems can be improved and property rights established. Key issues suggested

for the dialogue were: factors influencing informal settlements; diversity of

patterns of informal settlement development; and diverse policy solutions,

including a gender perspective. The key to improved housing conditions is open

and transparent markets, but equally important are the steps laid out to create

these markets. In short: how systems can be made inclusive for all.

The following sections provide a summary of the main discussions points of

each regional dialogue, as well as the key issues that emerged.

Group 1 – Southern and Eastern Africa

Participants in this dialogue were from Botswana, Canada, Ethiopia, Kenya,

the Netherlands, Nigeria, Norway, Rwanda, South Africa, the United Kingdom and

Zambia. They drew from their own experiences of implementing upgrading

programmes in the region to discuss what they perceived as the main issues that

arise when trying to apply conventional approaches to slum upgrading. A number

of unintended consequences and reservations were described in the areas of slum

upgrading, granting title to property and implementing micro-finance projects.

Based on their experiences and knowledge of their own contexts, the dialogue

participants expressed concerns that upgrading, titling and availability of

finance would:

- appear to legitimize land invasions or illegal occupation;

- prompt residents to sell their property (or houses provided through a

project) and move to other slums;

- benefit men more than women, owing to the way tenure and ownership were

structured, as well as the way participation in such projects took place;

- leave the underlying causes of poverty unchanged, especially if

individual property rights were granted without support for accessing or

creating employment;

- benefit individuals at the cost of the collective or the community;

- create new landlord/tenant structures, by allocating property to an

individual on plots originally occupied by more than one family;

- benefit existing landlords and displace tenants, since improved service

quality could prompt the owner to raise rents;

- generally disrupt complex and sensitive social networks that exist in

informal land arrangements but which are often destroyed through formalized

processes;

- lead to unaffordable rates and other high costs associated with

ownership;

- be less efficient for governments than simply building rental housing

managed by municipalities, compared to housing which is individually owned;

- in the case of micro-finance for housing, be used for consumption

spending rather than for home improvement; and

- lead to people becoming more indebted through loans and then forcing

them to sell their property at below-market value.

Given these concerns, it was recommended overall that slum upgrading and the

granting of title should not be conducted in isolation from other broader

processes of development, and particular attention should be paid to conditions

of macro-economic growth and participatory democracy. More specifically:

- Urban infrastructure investment which drives slum upgrading needs to be

undertaken within a policy framework of sustainable urbanization and a

broader city strategy.

- Upgrading of informal settlements should not be undertaken on a

settlement-by-settlement basis, but within a broader area-based framework.

- Surveying and registration need to be linked to broader settlement

development and upgrading processes.

- After understanding the macro and local contexts, the granting of title

must be designed to benefit people equitably, especially considering the

needs of the most vulnerable, and share rights between women and men, young

and old, landlords and tenants, and one generation and the next.

- Ownership should be one option, and rental and other tenure arrangements

such as group rights should be made available as viable alternatives to

allow people to make rational trade-offs depending on their situation.

- Titling should be coupled with education around the accompanying

limitations and obligations.

- The objective of surveying and titling (or the establishment of other

forms of tenure) should be to create predictability and to build trust

between people (e.g. between neighbours, between residents and local

authorities, between residents and politicians).

- Creating trust between property owners (or people with other types of

secure tenure) and lending institutions may be a much later development when

property becomes collateral for loan finance, but it is not a sound initial

motivation for establishing individual title.

- Property rights should be enforceable if they are to be meaningful. High

incidences of dispossession of land would indicate that the prevailing

system of property rights is inappropriate.

A number of conclusions for the way forward were put forth in the dialogue:

- Work towards pro-active land use management and planning.

- Build upwards to achieve the density required for the number of people

that need to be accommodated in the limited space available.

- Explore new methodologies for access to finance.

- Work towards decentralizing land registration processes and establishing

local commissions to regulate the process with transparency.

- Consider upgrading informal settlements within a broader planned urban

renewal context.

- Link slum upgrading with rural land use improvement for better incomes.

- Devise simpler titling systems for housing.

- Promote a shift towards a group/cooperative approach to housing

development.

- Capture experiences and disseminate knowledge directly to communities.

Old Fadama, Accra, Ghana. © Suzi Mutter

Group 2 – Asia and the Pacific

The Asia dialogue included participants with experience from Cambodia, China,

India, Indonesia, Sri Lanka and the Pacific Islands. There was an initial brief

discussion regarding the advantages and disadvantages of land titling, recalling

the recent debate initiated by Hernando De Soto’s book, “The Mystery of

Capital”.

A discussion followed on the legal and institutional pre-requisites for

effective land use management and on whether governments are willing to make a

shift from ‘donorship’ to ‘ownership’. The participant from Cambodia proposed a

number of pre-requisites, including:

- capacity, which is the most important factor, and the need for a new

generation of staff;

- appropriate institutional arrangements (in the case of Cambodia, a

council was set up for developing the land policy, and 17 ministries are

members, reflecting the fact that land is a cross-cutting issue);

- openness to the private sector;

- viewing land reform from a financial perspective, including land

valuation;

- realistic targets for titling;

- dispute resolution mechanisms that are pro-poor, straightforward and not

costly.

The participant from Cambodia also mentioned that with the quality of titles

produced in the country, the security of transactions is very high, and banks

will provide up to 50 percent of the value of the land as a loan. At the same

time, one of the impacts of land titling is that land value increases were

significantly higher and the poor were selling it at a much lower price, with

the result that the rich were capturing the majority of the land value increase

due to titling.

Discussions also revolved around titling vis-à-vis customary and legal

frameworks, with some proposing that the former be assimilated into the latter,

and others proposing that titling begin from customary law and build from there.

The question also arose as to how to make certificates more valid, since in many

areas they are not accepted by banks as collateral, thus preventing poor people

from having access to financial services. It was felt that it is critical to

demonstrate that the poor have the ability to repay and to save, in order for

banks to have a better understanding of their capacity. The need was also

expressed to have systems that can marry access to finance to ever-improving

certificates. How can certificates be made stronger?

The group discussed the need to have incremental approaches to land and

finance access in order to minimize market distortions and put less strain on

the administrative system. In this regard, as a group, people are better

positioned to withstand livelihood shocks and access credit, and certificates

gain in value as individuals create a positive credit history over time.

Building trust was considered paramount. As people achieve a certain level of

income, they gain more confidence in the formal system, and informal systems are

gradually pared down.

The complexities in the Pacific region were also discussed, in particular the

situation of people who are not landless but are not in high-land-value areas.

They move to urban areas, cannot get land and end up in informal settlements. In

China, on the other hand, many people give up their land rights and gain rights

to an apartment, not to a land parcel. One particular problem in China is access

to credit. The financial system is not fully developed, and the government and

banks are trying to learn from other countries in order to perfect legislation

and the mortgage system, with a view to avoiding consequences similar to the

sub-prime experience in the United States.

The role of private financing was also discussed, especially since land is

becoming increasingly scarce. There is a need to reserve a certain percentage of

privately developed land for low-income people; people who had been moved out

should have first rights of access, and private developers need to provide

infrastructure such as schools and clinics.

A number of overall conclusions were put forth during the dialogue:

- Developments are best served by an incremental approach, with collective

loans carefully administered at first, and then moving to individual loans

over time.

- Massive land titling doesn’t work; certificates work better, evolving to

more mature property rights over time.

- People prioritize legal certainty of land rights for the following

reasons: (i) security of tenure/ reduced risk of eviction; (ii) the ability

to pass on their asset to their children; and (iii) ability to access

credit. People need to be able to access credit without having to risk their

land asset.

- Small loans need to be able to evolve into larger loans and then into

some form of mortgage. Communities can increase their power through savings

schemes or by using traditional institutions.

How to assist local community savings groups such as Riverside slums in

Jakarta, Indonesia where residents want to organize their own plan for

upgrading, seeking private sector capital for their new apartments constructed

to be above the flood danger level. © Michael Mutter

A number of issues emerged from this Dialogue session, which included several

participants each from Ghana and Nigeria, as well as others familiar with the

West African context.

Some of the key issues discussed were as follows:

- Collaborative approach. Are institutions of surveyors working in

isolation, or are they bringing anyone else (e.g. service providers) on

board? A collaborative approach is essential.

- Capacity building. There was a strong call for more capacity

building, recognizing the shortage of schools to train in developing

countries, and the need for capacity before talking about any large-scale

titling.

- Diversity of contexts. Nigeria, with 60 states and 25 tribes,

offered an example of the diversity that exists within a country and the

importance of not generalizing solutions. The reasons for slum formation and

development differ, and careful research is required to understand different

contexts. Examples illustrated that slums and informality may exist for

reasons other than – or in addition to – poverty. For example, lack of

transportation can lead wealthier groups to choose to build informally close

to work, even if they own land in rural areas.

- Advantages and disadvantages of titling. Intense debate took

place on the possible advantages of a land title, triggered by Geoffrey

Payne’s presentation. Some thought that land titling must be conducive to

accessing finance, even though it is clear that a poor person in possession

of a land title will not automatically gain access to credit. Communities

need to save and have some form of land relationship that helps them develop

incrementally in an affordable way. Examples from Ghana and Nigeria included

the use of para-legal titles that the financial company would accept to

secure the loan. It was also suggested that one of the negative outcomes of

titling is that it creates a “black and white” scenario – going directly

from informal to titling can obscure the full picture. Assessments and

gender analysis are needed at the outset to ensure that vulnerable areas and

groups are not excluded.

- Taxation. Taxation of property has the benefit of making money

available to improve the environment for the general public. Some kind of

register is needed in order to establish a taxation system, but this does

not need to be land titling. At the same time, in many developing countries

taxation is on the poor, and the wealthiest property owners are not taxed –

this is clearly linked with corruption and weak land governance.

It was agreed that land titling should not be an aim in itself. If there is

no rule of law to support the rights attached to these titles, they are

virtually useless. Good land governance is therefore critical.

It was also emphasized that slum upgrading requires a holistic approach;

facilities and services such as sewage, water and security should not be

addressed individually. In addition, contemporary forms of collective tenure

need to be explored, and more research is needed to build knowledge on its

evolution and impacts.

The dialogue concluded with a focus on the role of local government. How can

FIG work more closely with local governments, including associations of local

government? If local governments do not have the capacity to work with slums,

ultimately nothing will happen. FIG also needs to work more with planners. In

all cases, solutions need to be found locally, and local governments need to

have the will and capacity, and access to information.

Slum Upgrading Facility in Ghana. © Michael Mutter

Group 4 – Central and Eastern Europe

The Central and Eastern Europe dialogue included participants from Croatia,

Germany, Greece, Iraq, Israel, Norway, Russia, Turkey, the Ukraine, the United

Kingdom and the United States.

More than 50 million people in at least 15 European countries are affected by

poor land administration and cadastre systems, with a lack of clarity and

transparency in land tenure and property rights. Lack of clear planning regimes

or a lack of enforcement of existing plans leads to massive illegal construction

in urban areas. The dialogue focused on a number of factors influencing informal

settlements.

A wealth of country experiences and examples were given. In Serbia, one

million illegal buildings have been constructed over the last 20 years, and the

issue is how to bring them into the formal system and register them without

accompanying high fees. In Russia, the speed of building construction is very

high, with adverse environmental consequences since planning regulations are not

designed for dense urban construction. In addition, in suburban cities there is

illegal construction on agricultural land. A participant from Iraq noted that

the country is still suffering from poor land management and unclear property

rights. Updating of cadastral maps is extremely slow, and the information is

outdated, with British maps from 1920 being used.

The issue of enforcement of regulations was intensely debated, with some

participants insisting that the destruction of illegal structures is the best

solution; others felt that such a measure was far too severe. Corruption was

widely acknowledged as a major impediment to enforcement and a factor that was

exacerbated by land management procedures that were not transparent.

The following key issues emerged during the dialogue:

- Informal construction has two principal and different motivations:

construction by poor people for basic shelter; and construction for

upgrading private real estate and for profit, usually in areas where real

estate values are high.

- The term legalization may not be the best term when applied to

addressing informal settlements. Decentralized or environmental upgrading

may be more appropriate to use when talking about acknowledging, in some

way, the existence of “informal” construction or settlements.

- Legalization is not a panacea. It needs to be to be complemented with

environmental improvements and upgrading of settlements, all of which is

time-consuming and costly.

- Land use and planning systems must be developed at the municipal/ local

level, with the participation of individuals and communities. In addition,

taxation is an indispensable tool that should be used to collect revenue to

be reinvested locally so that people see the immediate and local benefit.

Consideration should be given to needs of the taxpayers and not simply to

those of the legal owners.

- Public land administration needs to be equipped with modern tools such

as spatial data infrastructures, cadastre and e-governance in order to be

able to quickly and effectively address emerging demands arising from

urbanization. Moreover, it needs to be simplified to prevent undue delays

that would in itself promote illegal construction. People are willing to

respect laws if they are efficient and respond to their priorities.

- Post-conflict areas require particular attention, as land tenure

security in these areas is particularly threatened, and often in the absence

of public records or responsibility.

- Documentation and recording of property should include legal as well as

illegal dimensions.

- Land use changes may not comply with safety regulations, and attention

needs to be paid to these changes.

- Stable land policies will encourage investment in the maintenance and

upgrading of newly privatized land or property in countries in transition.

- Demolition of buildings is never a popular intervention. Only buildings

which are clear environmental hazards should be demolished.

- Corruption can be minimized through developing policy and regulations

that are clear, unambiguous and transparent.

- Land administration systems need to consider preventive remedies. In

addition over-regulation can be a barrier to affordable housing.

Across Albania, ALUZNI is in the process of legalizing 681 informal zones,

(23,000 ha). ALUIZNI has recorded some 350,000 requests for legalization, out of

which some 80,000 are multi-dwellings apartments and shops. © Doris Aldoni

Day 2 – Just and Sustainable Shelter

Finance Systems

Day 2 began with plenary presentations that outlined how financial

services are expanding to reach the urban poor. Four parallel “Dialogues

addressing various links of the land administration chain” were held, again

focusing on an exchange of experience, but this time from different professional

perspectives. The objective was to enable a cross-cutting development of the

links between individual links in the chain. Participants chose between four

sessions: Practices and Tools; Reinventing Planning; Linking Financial Sources;

and Access to Finance. A wealth of real-world experience was shared from around

30 countries.

This section summarizes the key points made in the Plenary speeches and in

the Dialogues.

Land Administration and Finance Systems

Expanding the Outreach of Housing Finance for the

Urban Poor – A Matter of Cooperation Combined with Sufficient and Appropriate

Due Diligence

– Mr. Michael Mutter, Senior Advisor, Slum Upgrading Facility, UN-HABITAT

|

© FIG |

Mr. Mutter opened his presentation with the question: “Why should we

be discussing finance for the urban poor in 2008 when the rest of the

world is suffering a major credit crunch resulting from massive

miss-selling of loans to the poor in North America?” The most

asked-for element in upgrading demanded by slum dwellers is access to

formal credit for loans for them to construct their own houses. As

things stand, poor people cannot afford credit since for them it is

exorbitant. This is because existing housing finance systems are not

geared to their needs. As a result, they fall prey to exploitation by

loan sharks at the informal end of the market, and to the high interest

rates of the formal market, both of which are linked to the perceived

high degree of risk for the lender. |

Mr. Mutter elaborated on the ‘slums investment deficit’ – the

contrast between what poor people can do and put up with in an environment where

they are not formally accommodated or sometimes even acknowledged, even though

they provide the city with its base resources, namely, the labour and

entrepreneurial skills that support the city economy. Currently, the ‘slums

investment deficit’ is lop-sided. The slum dwellers are the investors in the

urban economy and the ‘authorities’ do not keep up with them. The slum dwellers

have incredible resources, and the slums have tremendous unrealized

value. To be productive they need investment. He then provided some examples of

community-led housing finance schemes in Namibia, Pakistan, the Philippines,

South Africa and Thailand.

Mr. Mutter emphasized the growing understanding that the key to

up-scaling the provision of water, sanitation, housing and neighbourhood

development in developing countries is more successful and sustainable where

innovative financing mechanisms are used that involve commercial project loans

coupled with direct repayment elements by the householders themselves on a group

basis. He described the three basics for slum upgrading and prevention which are

core to investment decision-making:

-

Land availability and land security – meaning that once

occupied, the occupants will not be forcibly evicted. In this respect the

FIG’s role in working towards formal recognition of land security in

multiple forms specifically designed around the capabilities of the urban

poor can be seen as part of the due diligence required for finance.

-

Responsibility of municipalities to ensure basic affordable

services – road access, drainage, sanitation and water supplies, etc. – this

may require credit facilities against the revenue generation of the entire

city asset base. Water and sanitation can be seen as an entry-point for

municipal action in slums. Understanding costs is crucial, especially

keeping the cost of construction in check. For example, the cost of a bag of

cement rises daily. But do we need to use so much cement? There are other

construction methods and this information needs to be brought to the local

level.

-

Access to formal and affordable lines of credit specifically

for the slum dwellers’ own projects – such access is dependent upon the land

and services issues being agreed with local authorities as a basis for

community groups approaching the commercial banks for their involvement.

Savings schemes and cooperative structures help banks understand the

containment of risk to which they will be exposed.

SUF has found that such processes can be best achieved through

the establishment of local finance facilities that can offer credit enhancements

or guarantees to act as a stimulus for the application of loan products from

local financial institutions – the commercial banks. In this case the community

savings can be increased by acting as a local guarantee arrangement for

household groups or cooperatives to take loans on a collective basis. These

Local Finance Facilities provide the technical assistance that can package the

slum dwellers’ own upgrading multiple projects with the business plans for the

repayment mechanisms and other finance agreements that can be understood clearly

by the slum dwellers (the ‘clients’) and by the credit committees of the

commercial banks. In addition, credit enhancements can be offered by the Local

Finance Facilities to provide the necessary comfort for the commercial banks to

close the deals with the slum dwellers. This process is called ‘Finance Plus’,

in which the multi-stakeholder board is a problem-solving group able to help the

slum dwellers’ projects gain competitive formal credit through their detailed

‘due diligence’ of the projects.

Mr. Mutter concluded by explaining the difference in approach –

housing upgrading schemes are based on the plans of community groups (as opposed

to individuals accessing bank loans), which creates greater ‘due diligence’ of

the process leading towards the formal credit facilities. This is where a sound

methodology leading towards a Project Business Plan process comes in – and

results in a clearer picture of sustainable financing. This is working in

practice, and is the model needs to be developed and expanded.

|

© Michael Mutter |

Kenyan example Point of contact for the community is essential

as part of a new approach to city planning, able to deal with the

problems associated with degraded residential occupancy at the urban

margin, then able to deal with:

- Project Financial Packaging through development of a Special

Purpose Vehicle (SPV) Development Company or Housing Association,

engaging with domestic capital markets and commercial retail

lenders.

This has attracted Rockefeller Foundations for funding. |

|

This women’s savings group is linked with the Women’s savings Bank

Federation and slum Dwellers International. they thus have a track

record of full and timely repayments, well able to attract commercial

bank loans for development. © Michael Mutter |

Sri Lanka example Financial packaging for three large-scale

slum upgrading initiatives with the Colombo and Moratuwa City Councils,