Article of the Month -

November 2003

|

The Situation of Geomatics Education in Africa –

An Endangered Profession

Heinz Rüther, South Africa

1) This paper has been

prepared as a keynote paper to the 2nd FIG Regional Conference in Marrakech,

Morocco, December 2-5, 2003. It is also a background paper for the Round

Table on Surveying/GIS Education in Africa which is organised December 2,

2003 in Marrakech.

This article in PDF-format.

This article in PDF-format.

1. INTRODUCTION

The author introduced a paper on trends and needs in survey education

(1997) by stating that “the survey profession world-wide is faced with the

necessity of having to redefine its role in society and technology. It is

threatened with marginalisation, down grading to a service provider and,

potentially, loss of its professional status unless a new professional

profile is developed and supported by education and practitioners alike.”

The profession worldwide, but especially in the developed world has largely

responded well to the challenges of this period of change and paradigm

shifts. New technologies were embraced readily and the area of

geo-information was integrated in the survey discipline. Educational

institution partly lead the way in this process and partly followed

reluctantly, adapted their syllabi the name of some departments were changed

to incorporate Geomatics or Geoinformatics in one way or other. However,

this is not true for large sections of the profession in Africa (throughout,

this paper uses “Africa” to refer to Sub-Saharan Africa excluding countries

of the Sahel and North African region) and especially the educational sector

is under increased danger, and in some countries close to complete collapse.

The paper addresses the situation of surveying/Geomatics in sub-Saharan

Africa from the perspective of a survey educator in Africa. The author

perceives the profession in Africa as being under severe threat as a result

of a number Africa-specific as well as internationally occurring phenomena,

among these are the economic situation in Africa in general and specifically

that of educational institutions, the image of the profession, donor

policies, the development of black-box technology, lack of resources and

political instability.

2. GENERAL OBSERVATIONS ON CONDITIONS FOR EDUCATORES AND PROFESSIONALS

The author is not qualified to make an assessment of the economical and

political situation of the African continent in all its complexity,

uncertainties and contradictions. Numerous papers and reports on these

topics have been produced over the last decades and every possible political

and economical theory and philosophy has been applied in attempts to solve

Africa’s problems. Many of the proposed solutions are unrealistic, while the

valid models often encounter unforeseeable problems beyond the control of

both the African population and the developed countries involved in

development activities.

The paper is based on the author’s experience as external examiners in

six African Universities, visits others as well as to numerous survey

offices in Africa and work with African professionals. On this bases some

general observations are made regarding the situation of educational

institutions and the profession.

For a professional or educator in the developed world, who has never

visited the African continent, it is difficult to envisage the situation

common to many African departments of tertiary education, government survey

offices or survey practices. Some of the many problems complicating the

educator’s and professional’s life in Africa are:

- Academics often do not have a computer on their office desk and have

to book time in computer laboratories with a limited number of low-end

computers

- Offices are often poorly equipped and even telephones are not on

everybody’s desk

- State of the art software is seldom available and digital technology

is not well advanced

- Electricity blackouts are common, even in major cities

- Internet connections are painfully slow and unreliable, giving African

academics and professionals the unjustified reputation of being poor

E-mail correspondents

- Available survey equipment is often outdated and in a poor state of

repair and libraries are typically ill equipped

- Classroom facilities are poor and an overhead projector is often the

most advanced teaching equipment available

- Very few staff members have research experience and PhDs are not

common

- Salaries are generally low and academics have to spend significant

time on external activities to augment salaries.

The picture painted here is bleak and fortunately not reality in all

African Universities and institution, but it is certainly true for many, if

not the majority of educational institutions and government as well as

private survey offices on the continent. There are some exceptions, and some

Universities in Africa, albeit very few, can offer facilities which come

closer to similar institutions in the developed world, but none have the

facilities and resources of these institutions, with the possible exception

of South Africa. As anecdotal evidence one can quote the extreme case of a

regional government survey office, responsible for the land administration

of a large region in East Africa. Not a single computer found in this office

and cadastral records are kept in the form of pencil drawings on a 1:50 000

topo-map.

3. SURVEY/GEOMATICS EDUCATION IN AFRICA

Beyond the issues raised above, many educational institutions suffer as a

result of their typically very small student numbers. Small student numbers

render the departments or units relatively insignificant within their

respective institutions. Thus, educators in the discipline have little

access to the resources required for a modernisation of departments or for

marketing and often cannot respond to the needs as they would wish to.

On the other hand, educators have to deal with pressure from

practitioners who, not infrequently, hold the view that an entirely

needs-driven approach is appropriate in education and that the profession

should guide the educator. The author believes that educators need to be

more proactive than reactive. They must accept the responsibility and be

given the freedom to provide vision and guidance. Their ability to

extrapolate into the future, understand trends and explore new ground beyond

the present boundaries of the profession will provide skills and knowledge

for the future. If educators fail to interpret trends correctly or explore

new avenues, then there is real danger for the survey discipline to become

an insignificant service provider with a low profile. Little development

will take place in the discipline and many of its traditional areas of

expertise may be taken over by others. This potential downgrading of

surveying is an international threat, but especially threatening in the

African context, where the constraints of limited educational budgets often

make it difficult to address questions of education which go beyond mere

survival.

Unfortunately one, not infrequently, encounters the argument, that

cartographic needs in Africa are largely unchanged, that conventional survey

skills are still required and that thus education can follow its

conventional form for some time and that the concerns voiced above are not

yet relevant for Africa.

While this argument may have some merit, it is basically defeatist and

could lead to the demise of the discipline in Africa. First world expertise

and black-box mapping systems are likely to dominate the region and African

surveyors/Geomaticians could be reduced to purely operational functions.

This must be avoided under all circumstances. African institutes of

education must educate internationally acceptable and marketable experts,

world class scientist must come out of the research units of African

Universities, appropriate technologies for Africa must be developed in

Africa and African experts must manage activities with African technicians

responsible for the execution of such activities. All this must be done on

the basis on first world knowledge and in close contact with international

educational institutions, but nevertheless with a high degree of

independence and self-reliance.

4. THE SITUATION OF SURVEY/GEOMATICS DEPARTMENTS AT AFRICAN INSTITUTIONS

OF TERTIARY EDUCATION

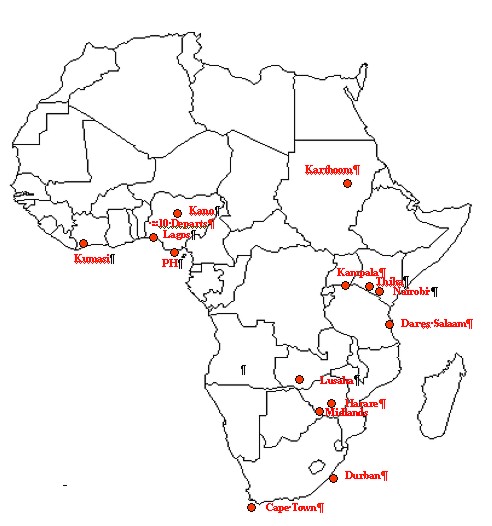

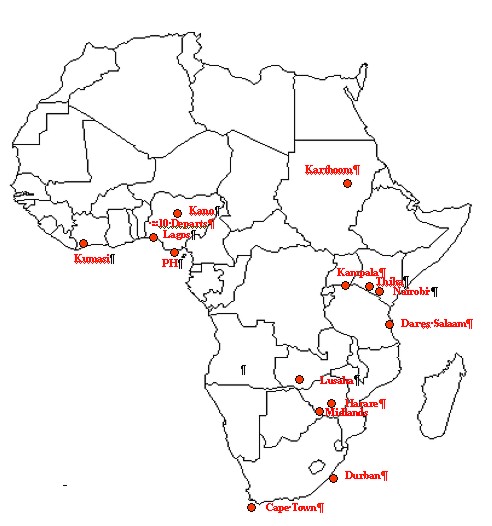

At first sight (Figure below) the distribution of survey departments in

sub Saharan Africa does appear somewhat sparse but by no means desperate.

However, viewed against the lack of current maps, the need for development

and specifically the situation at individual institutions, the picture is

much less encouraging, if not outright dismal.

Universities

Survey/Geomatics Departments in Sub-Saharan Africa

A brief assessment of the situation of survey/Geomatics Departments in

the sub-Saharan region will show the reality of discipline related education

in this region. Beginning with South Africa, in the early 1970s there were

five independent departments, one each at the Universities of Johannesburg,

Pretoria, Durban, Fort Hare and Cape Town, with just under ten Chairs of

Surveying or Photogrammetry. Today, there is not a single independent

Department in South Africa and only one Chair of Geomatics has survived.

Departments in Pretoria, Johannesburg and Fort Hare were closed as a result

of poor student numbers, while the Durban department was amalgamated with

Civil Engineering and is left with three full time staff members. The Cape

Town department has recently been incorporated with the School of

Architecture, Planning and Geomatics withy five remaining staff members at

the University of Cape Town, one of which is the Chair of Geomatics.

Unconfirmed reports from Botswana indicate that a Survey department will

be established at the University of Botswana in Gaberone. This is a

surprising development for a country with some 1.5 million inhabitants, in

view of the closure of departments in neighbouring South African with a

population of more than 40 million. A survey diploma, previously offered by

the Department of Civil Engineering, has been discontinued some years ago.

In Zimbabwe there are two University Departments, one at the University

of Zimbabwe in Harare and one recently established at the State University

of the Midlands. The Harare department has at present one staff member while

the newly establish Midlands department with three full time staff members

seems to be growing in relevance and might well take on the previous role of

the department in Harare as the leading department in Zimbabwe.

The University of Zambia has a survey department, which appears to be

severely under-resourced and little is heard about activities in the

department. Staff members of the Zambia department show no presence at

conferences and symposia in Africa and no research papers have been

published in journals.

One of the more fortunate countries, as far as surveying education is

concerned, is Tanzania, where a Department exists at the University College

for Land and Architectural Studies. The department with close to twenty

staff members and over 100 students has grown out of the former Ardhi

Institute and has made an excellent effort to grow from a Technikon to a

University level. Nevertheless, the department experiences all of the

typical problems of insufficient equipment, few computers, poor Internet

facilities, frequent power cuts and very limited resources; also, there is

no Chair of Surveying at this institution.

Moving further north to Kenya, there are two departments, one in Nairobi

and one recently established at the Jomo Kenyatta University of Technology

in Thika. The department at the University of Nairobi, with 13 staff members

and 150 students, belongs to the small group of survey departments in Africa

with a significant tradition as an institution of higher survey education.

As far as facilities, resources and problem areas are concerned, there is

little difference to other African institutions with the one exception that

there is an established Chair of Surveying. The department at Jomo Kenyatta

is three years old and has an academic staff of four and 75 students in

three years. They are provided with teaching assistance from staff members

from the University of Nairobi and the UN-ECA Regional Centre (RCSSMRS) in

Nairobi.

The department at the Makerere University in Kampala, Uganda with 12

staff members and some 50 students is one of the oldest survey departments

in Africa, but today, suffers from the same difficulties as other African

departments.

Survey departments also exist in Khartoum, Sudan and Kinshasa, Zaire, but

the author was unable to obtain any information on these two institutions.

Judging from the lack of presence at African and international survey

related conferences and in survey publications, one must assume that

activities at these departments are limited and it is unlikely that

resources are sufficient to develop international status.

In West Africa there are two countries with University Survey

Departments, Ghana and Nigeria. In Ghana there is a department at the

University of Kumasi, while Nigeria has a virtual glut of survey

departments. Here a total of nine University departments offer a degree in

Surveying and training in the form of short courses is provided at a

Regional Centre (RECTAS) in Ile Ife. Reports from this country also indicate

a dearth of resources in Geomatics Departments.

It is noteworthy that there are only two remaining University Chairs for

Surveying between Cape Town and Khartoum including the entire African Region

South of the Equator. This is a clear indication of the status and relevance

of survey departments in the eye of University authorities in this area.

The UN-ECA Regional Centres play an important role in training,

consulting and coordinating of survey initiatives in Africa, but they do not

provide education in the traditional sense. They offer short courses and

thus fill an important gap, where Universities lack the human resources.

In view of the above, there can be little doubt that survey education in

Africa and subsequently the profession itself is under severe threat. Too

few and insufficiently prepared graduates enter the profession and, due to

their numerical skills, their ability to think in a structured and logical

fashion and their understanding of spatial problems, the best candidates are

often ‘pirated’ by companies and institutions without activities unrelated

to surveying.

5. RESEARCH AND POST-GRADUATE EDUCATION

Generally, research in an educational institution has three essential

objectives, these are the development of

- the student

- new methods, algorithms, instruments or systems and

- the supervisor’s deeper understanding of the discipline

This threefold relevance of research is often overlooked and research is

evaluated solely on the basis of the second criterion, the tangible research

output. The author is of the opinion that the first objective, the personal

development of the student, is of much higher relevance in post-graduate

research than the research product. One can even go so far to premise that

gaining knowledge in the particular research area, as important as it may

be, is of secondary relevance for the development of the students and that

the ability to abstract from the literature, analyse critically, structure

thoughts in a logical fashion, formulate a readable document and learn self

management should be the principal objectives of post-graduate research.

Post-graduate research is also essential for the supervisor, who is

forced to continually improve own knowledge and critically assess own

understanding of the discipline and the research area. The author firmly

believes that excellence in teaching at university level is primarily based

on the teacher’s research activities. Further, the improvement in

professional maturity observed by the author in post graduate students under

his supervision has convinced him of the invaluable contribution made to the

profession through post graduate programs. Africa is in desperate need of

academics and professionals with research experience and Africa based

post-gradate education is essential. Most unfortunately, at present

survey/Geomatics research and post-graduate education is restricted to very

few departments on the continent. It is therefore most important to

establish post-graduate programmes, both in the form of taught courses and

full research projects, at African Universities.

The present poor research culture at most African Geomatics departments

can be attributed to

- the previously mentioned need for academics to spend a significant

amount of their time on consulting and other activities to ‘make ends

meet’, leaving little or no time for the unlucrative business of research.

- the lack of funds for research

- the lack of research experience

- the lack of a cohesive framework for effective coordination between

institutions and lack of South-South research projects

Africa based research is one of the principal factors with a potential to

improve the situation of Geomatics education in Africa, as it will raise the

status of departments within Universities, increase the relevance of

Geomatics in an national contexts, improve teaching capacity, create a wider

interest for academic staff and thus their commitment to education. The

author considers this area as the one where the most significant impact can

be made with the least expenses.

It must be noted, that Geomatics research projects do exist in Africa,

but that these are generally driven from outside with limited local

participation.

6. THE STUDENT PERSPECTIVE

African students largely depend on government subsidies, donor support or

bank loans, the latter are difficult to secure and more difficult to repay.

Especially students from rural communities suffer in this regard as they

typically come from the poorest economic backgrounds and are often supported

by their family at the expense of their siblings. In return, they are

expected to support large families which have contributed to the students

expenses, once the student has graduated. This obligation to the family is

taken very seriously and can represent a considerable psychological burden

for the student. The inordinate pressure to succeed, resulting from this,

can severely affect the student’s frame of mind and his/her ability to

study. Concerning Gender it must be mentioned, that in many rural areas the

view still prevails that a woman’s role in life is that of a housewife and

that a professional career is utterly inappropriate for a woman.

Student numbers vary widely, with South Africa, once a country with one

of the leading survey education system in Africa, now has the lowest student

numbers on the continent, while east African countries and Nigeria have

programs with of 10 to 50 students in each of the four or five years of

study. The reasons for the low numbers in South Africa are not certain, but

likely to be a result of the poor image of the surveying as a lucrative

profession, lack of awareness of Geomatics, a reluctance to work in a

profession with a field work component and the lack of schools which teach

mathematics and science at a sufficiently high level. The relatively large

students numbers in other African countries, on the other hand, are a

positive development, but must be seen against the situation of a profession

under severe threat and the potential lack of employment opportunities.

Initiatives are there fore required to improve both, the situation of the

profession and education on the continent.

On the optimistic side, one can report that the change from surveying to

Geomatics has had some positive effect on the demographics of the student

population. Fieldwork in Africa is not without hazards and the thought of

having to spend weeks in the field as a female has previously made the

survey profession unpopular with female school-leavers. Geomatics has a

different image and is not perceived as being associated with extensive

periods of fieldwork; as a result, larger numbers of female students are now

registered.

7. INTERNATIONAL SUPPORT AND DONORS

There can be no question regarding the necessity for international

support for Africa. However, one can question the form this support takes.

With respect to surveying there are two aspects which are relevant, these

are graduate and postgraduate student support and project funding.

It has been a tradition for donors to provide bursaries for African

students for studies in universities of the developed world and specifically

the donor country. As valuable as such support is, it also has its severe

disadvantages. Having experienced the quality of life in a developed country

with all its material and academic resources, many of the best students

choose to remain and enter academia or industry in a country outside Africa.

Those who return, on the other hand, face working environments where they

have no access to any of the equipment or software they have been exposed to

during their studies. In fact, they might be quite incapable of coping with

these limitations and frustration can set in. A further, and possibly more

destructive effect of the transfer of students to the developed world, is a

reduction in student numbers at African Universities, aggravated by the fact

that the best students are selected for overseas studies. This serves to

further aggravate the problems of university departments.

A change in donor policy in this respect would appear essential, and the

most acceptable solution would be a compromise in the form of

sandwich-course. Students would then have the opportunity to benefit from

state-of-the-art technology and expertise in the developed world without

loosing contact with conditions at home entirely.

Donors should also consider providing more direct support to African

University departments through equipment donations and assistance with

South-South networking of institutions, academics and students.

Donor activities have an even greater negative impact on the profession

through the conditions often associated with the provision of funds for

mapping and survey projects. Typically, experts from the donor country are

employed and data processing is done in the donor country. Capacity building

components are routinely included into donor-funded projects and

sustainability is a key issue. In reality however, the human capacity

generated during the project is often not utilised once the work has been

completed, equipment is unused and gathers dust and the newly trained staff

moves elsewhere. It is difficult to identify reasons for this common

phenomenon. It would seem that incentives to carry on with project disappear

together with international consultants and projects often die a quiet

death.

Globalisation has not bypassed the survey profession in Africa and

numerous firms from the developed world carry out major mapping and survey

projects in Africa. With their high-end technologies, stream lined

production processes, state-of-the-art hard and software and experienced

staff, they represent a fierce and practically unbeatable competition for

the African professional surveyor, who can at best hope to obtain a

sub-contract in one of the internationally financed projects.

8. NETWORKING

African countries can be grouped in a variety of configurations according

to geography, language, history and colonial past, religion, political

leaning and other criteria. One of these historical groupings separates

Francophone, Anglophone and Portuguese speaking countries,

The divisions are not merely nominal and have inhibited the flow of

information and movement of individuals between regions, a phenomenon also

reflected in survey/Geomantics activities. Language is the principal medium

of education and the language division plays a more significant role in this

area than in most other spheres of professional activities. There is little

mutual knowledge of educational institutions in Africa, standards differ,

staff exchange is very limited and students seldom transfer between

institution within Africa and typically prefer to advance their studies

elsewhere. There still appears to be a perception that quality in education

can best be provided outside Africa. Although it must be accepted that -

largely for historical and financial reasons- Geomatics educational

standards outside Africa are on average higher than in Africa. However, it

is equally true that centres of Geomatics excellence do exist in Africa and

that there are no reasons why other African institutions could not reach

international standards.

Recent developments and the activities of international and regional

organisation have reduced the level of separation substantially and

co-operation is growing. However, educational and professional links of

individuals, organisations and countries with the ‘first world’ still appear

to be stronger than those within Africa. It is important to change this

trend and increase inter-African co-operation at educational and

professional levels.

9. A BRIEF NOTE ON THE PROFESSION AND THE IMPACT OF INTEGRATED AND

‘BLACK-BOX’ SYSTEMS

The complexity of Geoinformation problems has lead to the need for

integrated systems. With the integration of the areas of data acquisition,

management, analysis and presentation as experienced in Geomatics and other

Geoinformation professions, there arises the need to integrate the tools

associated with these areas. It is no longer feasible to use a single

software package or a single technology to respond to the challenges of

Geoinformation issues and integration has become the key to efficiency and

quality (e.g. GPS/ GIS systems for rapid field-to-map solutions). The

advantages of such systems are obvious, but they come at a price, both with

respect to finance and capacity. A ‘blackbox’ approach is often adopted and

the user no longer sees how results are obtained, which tends to lead to

uncritical acceptance of outputs. Notwithstanding this, integrated systems

will be necessary and replace stand-alone units in numerous Geoinformation

applications. This development results in a dual threat for the profession

in Africa:

- the high cost of the systems make them unaffordable for the majority

of practitioners in Africa, thus given developed world professionals an

edge in tendering for projects.

- the ease of use of black-box technology has lead to the emergence of

numerous companies with unqualified staff producing apparently high

quality results, which often do not stand up to close scrutiny

While this is a universal phenomenon, it has a greater relevance in

Africa than in the developed world. This is due to the shortage of expertise

and the associated lack of quality awareness, where so-called experts are

allowed to employ black-box technology to produce low quality products. This

can bring the profession into disrepute. More importantly though, it results

in the trivialisation of the skills required for spatial data acquisition

and these skills are seen as a service providing rather than as a core

expertise.

10. POSSIBLE INITIATIVES AND SELF-HELP IN AFRICAN GEOMATICS EDUCATION

PROFESSION AND THE IMPACT ON INTEGRATED AND ‘BLACK-BOX’ SYSTEMS

Solutions to the multifaceted difficulties and problems highlighted above

are evasive and require significantly planning, commitment and change of

attitude from both, experts in the developed world and in Africa. Some first

steps towards a possible improvement could be:.

10.1 Educational Data Base

A number of databases of educational institutions in Africa are in

existence, however, these are often incomplete, not current, tend to be

restricted to listing staff members and at best curricula. The establishment

of a more comprehensive, centrally administered and current educational

database for survey/Geomatics would serve to provide for

| potential students |

a choice of institutions available for education |

| graduates |

transfer between institutions, and contacts of

potential supervisors for post graduate research |

| educators and researchers |

exchange of individuals, transfer into postgraduate

programs at other Universities, joined courses, distribution of teaching

over regions and identification of potential positions, a possibility

for joined research projects and communication on research issues |

| employers |

contacts for the recruitment for professional positions

|

10.2 Curriculum Design and Educational Standards

Survey/Geomatics curricula in Africa vary widely and some have remained

unchanged for decades. A modern curriculum content is essential to provide

state-of-the-art expertise and make institutions compatible with the rest of

the world in the eyes of prospective students and the public. Students are

well aware of this need, as recently became obvious when students

demonstrated requesting a modernisation of the Geomatics syllabus at an

African University.

Academic freedom must be guaranteed and each department must have the

freedom to design an individual curriculum. One could, however, consider the

design of an Africa-specific ‘sample’ or ‘best-practices’ curriculum, which

could be made available throughout Africa as a guideline to assist with the

development of new courses as well as with the assessment of existing

programs and – possibly - the provision of minimum standards for Geomatics

education.

10.3 Joint Postgraduate Programs and Short Courses

Other disciplines, such as Architecture and Planning, have introduced

post-graduate courses jointly administered and executed by a group of

Universities. This approach makes use of the specific strengths and

expertise of departments and allows students to experience different African

cultures and environments, while making potentially important contacts for

their career.

Similarly joint short courses could be designed, where instead of the

students, the teaching staff moves between Universities and provides

lectures in specific areas such as digital photogrammetry, GPS or GIS.

Students, staff and professionals alike could attend these courses.

10.4 General Networking between Educational Institutions and Joint

Research Projects

Mutual visits between educational institutions and joined research

projects are commonplace in Europe and other parts of the world, while they

remain the exception in Africa. African educators and experts can more often

be found at international conferences and research- or educational

institutions, than at corresponding events or institutions in other African

countries. Attempts should be made to establish contacts and arrange visits

in preparation of joined projects with the objective to create, within

Africa, the fertile atmosphere of close co-operation and friendly

competition as it exists in other parts of the world.

The objective of a united African Geomatics community should be the

research and development of appropriate technologies for Africa in Africa

and by African technicians, professionals, researchers and academics.

10.5 Formal Study of the African Survey/Geomatics Education Situation

This paper can only touch on the problems of survey/Geomatics education

in Africa and does not claim to have either identified all difficulties nor

does it claim to offer all the answers. A systematic study is required for

this purpose and it is suggested that a task group be formed to carry out

such a study and assessment of the situation and propose solutions and

initiatives.

10.6 Collaboration with other Institutions and Organisations

Geomatics departments at universities seldom work in collaboration with

other institutions. Therefore, efforts to develop collaborative work

involving African educational and development institutions, government

agencies, NGO’s and International agencies should be made.

10.7 Formation of an Association of African Survey Educators

An Association of African Survey Educators was formed in the early

eighties at a meeting in Cape Town arranged to address educational issues in

Africa. The author chaired this Association, which proved a total failure

and a perfect example of ‘how-NOT-to-do-it’. Members of the Association were

undoubtedly committed to the cause, but none of the planned activities could

be implemented nor were there any further meetings, as no funding for such

initiatives could be secured.

The author believes that it would be appropriate and prudent to now

reconsider the formation of an Association, consisting of staff members of a

representative range of educational institutions in Africa as well as a

limited number of educators and experts from the developed world. This

Association could be tasked with exploring the above listed as well as other

Geomatics related initiatives. The experience made previously clearly shows

that such an association can only function if it can be formally linked to

one or more donors and if financial backing can be mobilised.

10.8 Donor Support

Donors should be encouraged to not only support studies in the developed

world but also in Africa, to provide support for sandwich-degrees with study

years in and outside Africa and to financially assist university

departments. Further donors should be encouraged to increase the local

expertise content in development projects.

11. CONCLUSIONS

The paper has highlighted some of the threats to and opportunities of the

Geomatics profession in Africa from the point of view of an educator. It is

based on the assumption that that the profession has a significant function

in the development of sub-Saharan Africa and that survey/Geomatics education

is essential for Africa. It suggests that the profession is only sustainable

at educational institutions, if a broader view of the profession’s

activities is adopted and initiatives are taken to strengthen education in

the region. A need to protect the profession in Africa against isolation and

downgrading to purely operational levels is recognised and suggestions for

self-help development were made. The chance of success for the proposals

made here will, above all, depend on the enthusiasm of those participating

in the suggested initiatives and on the availability of funding. The

ultimate objective of any educational effort in Africa must be donor

supported self-help development towards a largely independent Geomatics

capability in the region.

REFERENCES

The paper is subjective and entirely based on the personal views and

observations of the author, derived form extensive experience in African

Geomatics education and work with survey professionals in Africa. It is not

a scientific study of the very complex situation of Geomatics in Africa and

therefore no references are provided.

CONTACTS

Heinz Rüther

Geomatics Division

School of Architecture, Planning and Geomatics

University of Cape Town

SOUTH AFRICA

Email:

heinz.ruther@eng.uct.ac.za |