Article of the Month - April 2023

|

The Surveyor Pirate of the Caribbean

John BROCK, Australia

|

| John Brock |

This article in .pdf-format

(19 pages)

In this article John Brock takes you to the early days of the

settlements in the USA together with land surveyor and architecht

Barthelemy Lafon. The paper presents an excellent

sample of surveys and edifices attributed to Lafon, along with tales

of some of his raids of piracy. Fascinating... Learn and explore

more about USA at the

FIG Working

Week 2023 in Orlando, Florida

SUMMARY

It appears that in the early days of the settlement of New Orleans,

Louisiana, USA, a career change from the profession of land surveying

and architecture meant venturing into the more lucrative, albeit less

legal, undertaking of a privateer, which is actually a more polite word

for pirate! Land surveyor and architect, Barthelemy Lafon, who had

hailed from France, built up an impressive portfolio of land surveys

combined with an equally extensive corpus of buildings attributed to his

designs. Who knows what influenced this locally reputable pillar of the

community to join with fellow Frenchmen, the notorious brothers Jean and

Pierre Lafitte, the enigmatic pair who had a spurious agreement with the

English and US overlords to sack Spanish vessels (and any others which

ventured into their territorial waters?) and skirted with a death

penalty to loot these hapless captains. It was indeed ironic that this

duo of treacherous characters avoided execution by rendering courageous

support to US General Andrew Jackson in conquering a much larger English

force in the Battle of New Orleans in 1815, virtually being the last

concerted effort by the homeland to suppress the rebellion of their

northern American colonies on US ground. This paper presents an

excellent sample of surveys and edifices attributed to Lafon, along with

tales of some of his raids of piracy.

KEYWORDS: Barthelemy Lafon, New Orleans surveyor,

architect, pirate.

1. INTRODUCTION

Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto discovered the body of the

Mississippi River between 1541-42, but it was not until the Frenchman

Robert Cavalier (Figure 1), Sieur de la Salle, erected a cross in 1682

at its mouth that the territory was formally claimed in the name of the

French Sun King, Louis XIV, for whom Louisiana is named (State of

Louisiana, 2023). In 1718, New Orleans was founded, being named after

Phillipe Duc D’Orleans, younger son of King Louis XIII, with the oldest

cathedral in the US, St. Louis Cathedral, being erected in that same

year. It was destroyed in the 1788 fire to be rebuilt in 1794. Adjacent

to this holy establishment was placed the Cabildo, the Governor’s

residence, in which the later mentioned treaty was signed in 1803. In

1762, the succeeding King Louis XV ceded all of Louisiana west of the

Mississippi to his cousin, Charles III of Spain, with the Treaty of

Paris formally confirming this transfer in 1763 (Chamberlain and Farber,

2014).

In the final years of Spanish administration from the great fire of

1788 to 1803, the enactment of Spanish building codes resulted in the

erection of Spanish colonial style architecture, particularly in the

ironically named French Quarter, such exteriors requiring stucco and

tiled roofs including customary patios and long iron balconies as were

found in the haciendas of southern Spain. Even after the formal

transferral of the Louisiana territories to the US in 1803, the elite

Creole planter-merchant class dominated commerce and the social life of

the burgeoning community for a substantial period from that event

(Chamberlain and Farber, 2014).

Figure 1: French explorer Robert Cavalier who

claimed the Mississippi River in the name of Sun King Louis XIV to later

give the name of Louisiana to the whole territory.

When the 3rd US President, Thomas Jefferson (also District Surveyor

for Albemarle County), signed the Louisiana Purchase Treaty on 30 April

1803, the continental land mass of the United States of America was to

be doubled, adding to its original 13 states all of the recently

acquired French territory west of the Mississippi River (Figure 2). This

amazing real estate transfer cost the US Treasury a mere US$15 million,

which, even in modern terms, was more like a ‘fire sale’ than a market

value transaction. 530 million acres (828,000 square miles) of land was

obtained for 3 cents an acre in what is the largest land acquisition in

US history (State of Louisiana, 2023). The final hand-over of the lands

from Napoleon Bonaparte took place on 20 December later that year.

|

Figure 2: Coloured green is the area of land

purchased by the US government from France by the Louisiana Purchase

Treaty, which was signed on 30 April 1803 for US$15 million – US

President Thomas Jefferson on the left and Napoleon Bonaparte on the

right (Rawat, 2018).

Immediately, at the mouth of the mighty Mississippi River, and to the

east, lay the new area later to be the State of Louisiana. Much of the

occupied land had Spanish tenants, who had inhabited the farms during

the Spanish occupation, which preceded the French ownership by about 40

years. In what could be described as the greatest land gazumping in

world history, France’s fanatical self-proclaimed ‘Emperor’ hoodwinked

the cash-strapped Spanish authorities by calling in a debt owed, so that

he could then swiftly pass on the extensive territories west of the

Mississippi to finance his failing battle against the English in arenas

of conflict on the other side of the planet.

It was a commensurate land swindle and double deal, but the new

states of America were unperturbed as they quickly absorbed the

ownership of these neighbouring lands into their vastly expanded

dominion. Although held under the Spanish flag, New Orleans had a

culture identifying with the many French settlers who had migrated from

their homeland with their descendants emerging as a white Creole

merchant/planter class mainly conversing in a dialect of French origin.

2. LAFON’S EARLY YEARS IN NORTH AMERICA

Born in 1769 (the same year as Napoleon Bonaparte!) in the old town

of Villepinte in the Departement de l’Aude, Province of Languedoc, in

France, along the Canal-de-Midi which connects the Mediterranean to the

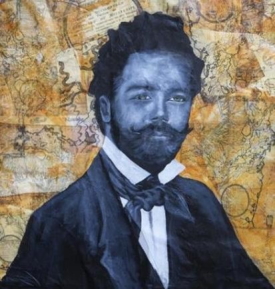

Atlantic (Cultural Landscape Foundation, 2023), Barthelemy Lafon (Figure

3) spent his first 20 years under the Ancien Regime with Bourbon kings

reigning over a nation where the privileged families enjoyed an elite

lifestyle. However, with his coming of age in 1789 came the Storming of

the Bastille on 14 July 1789, which started the French Revolution. This

uprising meant upheaval and often death to the Bourgeoisie, so he fled

the threat of the guillotine never to return to his birthland.

Figure 3: Portrait of Barthelemy Lafon by

Jessica Strahan (2018).

Possibly passing through the spheres of French influence in St.

Domingue or Haiti, he may have travelled through Cuba, but whichever

route he took he made his way to the ‘French’ Louisiana Territory

sometime around 1789-90. The sparsely populated lands are said to have

reminded him of his rustic origins in rural France, and despite Spanish

dominion over the territory since 1763, French was still the prevailing

tongue together with compulsory Catholicism for all residents. Thus, it

must have seemed like divine providence when Napoleon cut the deal to

take the lands from Spain, then just as expediently disposed of all of

the territory to the young US establishment in 1803 (see Figure A1 in

Appendix A).

Shortly after his arrival in his new home, Lafon established an iron

foundry in the lower area of Canal Street and a “brick plantation” in

1801 (see Figure A2 in Appendix A). The need for his architectural

services must have been in strong demand, particularly in the sphere of

public works repair projects. He prepared plans for the restoration of

the city gaol in 1794 due to its damage from the fire of 1788. Four

years later, he was called as an expert to assess the repair works on

the Presbytere and Cabildo, which was the residence of the Governor.

During the period from 1797 to 1799, he brought about improvements to

the covered gutters of the city, while in 1802 he reconstructed the

riverfront levees. For these intervening 13 years, Lafon was in the

right place at the wrong time because a terrible fire had destroyed much

of New Orleans in 1788, which could only be considered a wrong time!

However, for the newly arrived French architect/surveyor it was the

perfect time to join an economy craving new designs for lost residences

or restoration plans for partly damaged structures worth saving. His

expertise in hydraulic engineering was also keenly employed to build and

repair those levees damaged by flooding, which was a constant threat and

still is to this day. He was such a busy man that he engaged another

French-born surveyor, Jean Baptiste Pene, to assist him. He also

employed scribes to prepare many of his survey “warrants”. His survey

duties comprised verifying land grants and land purchases, along with

establishing precise borderlines between extensive rural French long

lots (which meant plantation properties along the Mississippi or the

numerous nearby bayous) or measuring boundary lines of the narrow urban

lots in New Orleans city. Every inch was important with his services

called upon to also evaluate the land for its potential usage (Edwards

and Fandrich, 2018, p.1-2).

His first private commission is probably in 1794 for a dwelling for

Mademoiselle Jeanne Macarty at the intersection of Conti and Decatur

Streets in a typical colonial New Orleans design with a brick ground

level containing stores, then a half-timber colombage second floor with

plastered formal rooms and wood-panelled chimney breasts. Some other

significant townhouses of the late Spanish colonial era accredited to

Lafon by stylistic comparison are such works as the Barthelemy Bosque

House at number 616 Chartres Street (c. 1795), a later 1790s residence

for Vincent Rilleaux at 343 Royal Street along with another 3-storey

premise at number 634 in the same street (Figure 4), and a c. 1795

building called Joseph Reynes House on a corner allotment at Chartres

and Toulouse Streets. In 1797, he was engaged to build a larger similar

home for the merchant Jean Baptiste Riviere at the corner of Bienville

and Decatur Streets, made taller by adding an entresol as well as

including more elegant features like carved mantles, a rose window and

pediment with a sculpture. He is also credited with the 1799 De La Torre

House, standing at 707 Dumaine Street, New Orleans (see Figure 4)

(Masson, 2012).

|

|

Figure 4: (Left) Lafon designed 1795 house at

634 Royal Street, and (right) the 1799 De La Torre House at 707 Dumaine

Street, New Orleans.

3. IN THE NEW ORLEANS SURVEYOR-GENERAL’S DEPARTMENT

As Masson (2012) put it, “Barthelemy Lafon enjoyed a long and diverse

career in Louisiana as an architect, builder, engineer, surveyor,

cartographer, town planner, land speculator, publisher and pirate.” Such

a quotation demonstrates the wide spectrum of activities with which

Lafon was associated, but it is quite an anomalous finale which includes

“and pirate”!

During his formative years in New Orleans, he carried out most

reputable projects in town planning, building and mapping together with

his many exploits in surveying, which create an image of a man fighting

between two worlds of existence. In a Jekyll and Hyde parody, he

performed the professional needs of his community to the fullest, but he

was clearly torn away into a life of swashbuckling adventure in the

dubious underworld of privateering, otherwise recognised as legalised

piracy. As his life story unfolds, this darker side of his character

will arise towards its finale. Nevertheless, his amazing professional

performance belies his disreputable demise.

One of Lafon’s early commissions included an 1803 survey of Galveston

(now Galvez, LA, near Baton Rouge) for the Spanish along with maps and

surveys of New Orleans. Having gained a solid reputation for his private

surveying activities, and despite two bitter disputes relating to two of

his architectural projects which may have sullied his name in this

field, he was seconded to the Surveyor-General of Orleans County between

1804-09, duly appointed by Isaac T. Briggs, Surveyor-General of the

lands South of Tennessee (Edwards and Fandrich, 2018, p.8). During his

service with this department, he still carried on with designing

buildings and creating green subdivisions in some of the new suburbs.

Lafon’s work as a surveyor was said to be “extraordinary”, both

working for private clients and the administration as well as designing

developments adopting the principles of European Garden City designs.

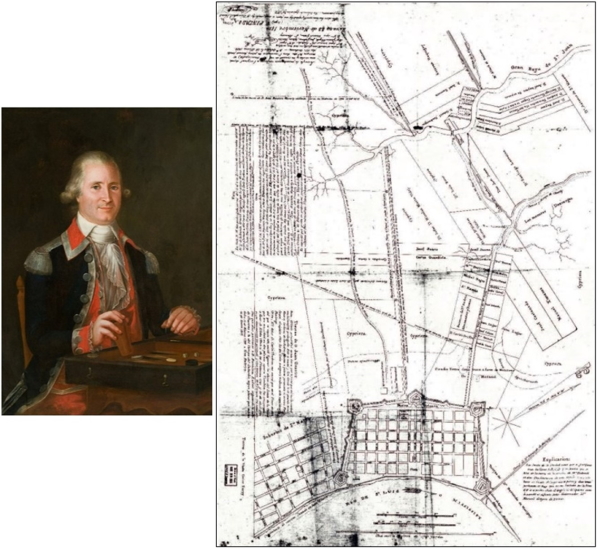

His initially preferred style of map preparation was based on his

Spanish Surveyor-General Carlos Trudeau’s style (Figure 5), but he later

began introducing his own features to the works, such as dual language

plans (Figures 6-9). He completed work on one of the earliest and most

accurate maps of Louisiana in 1805 called “Carte Generale du Territoire

d’Orleans Comorenant Aussi la Floride Occidentale et une Portion du

Territoire du Mississippi” (Figure 8). Some of his other plans include

Mouths of the Mississippi (1810 & 1813 – see Appendix B), English Turn

(1814), the Balise (1814), Port St. Jean (1814) and Fort Bower (undated)

on Mobile Point. Another map of New Orleans in 1816 illustrated the

rural areas with new suburbs created around the nearby plantations (see

Figure B3 in Appendix B).

His elaborate designs were shown on plans for the Lower Garden

District, which crossed five plantations (Soule, La Course,

Annunciation, Nuns and Paris) to include all land up to Felicity Street.

Being a connoisseur of the classics, he gave the streets the names of

the nine muses in Greek mythology: Calliope, Clio, Erato, Thalia,

Melpomene, Terpsichore, Euterpe, Polymnia and Urania. The sophistication

of his plans bore tree-lined canals, fountains, churches, markets, a

grand classical school, and even a coliseum. Most of these decorative

inclusions never materialised, but his grid pattern for the street

layout along with the parks and, of course, the street naming survived.

Figure 5: (Left) New Orleans Spanish

Surveyor-General Carlos Trudeau (aka Charles Laveau), and (right) the

1802 map of New Orleans by Carlos Trudeau.

Figure 6: 1802 Lafon map of Lower Louisiana and

Western Florida.

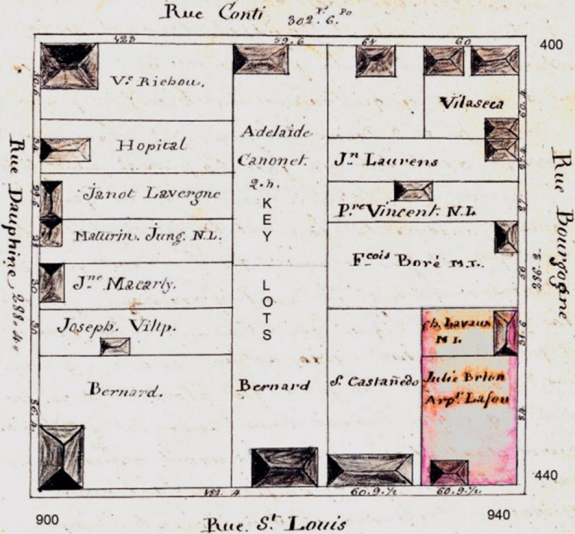

Figure 7: French Quarter Square 91, surveyed in

September 1804 (Lafon Survey Book No. 3, p.46). The allotment shaded

pink is the property acquired by Lafon at the time of this survey, it

being where the house in which he died was located (Edwards and

Fandrich, 2018, p.28).

In 1806 and 1807, he created influential subdivision plans of the

Delord-Sarpy Plantation, enlarging Fauborg St. Mary to resurrect Fauborg

Annunciation further up along the river. In keeping with European style

trends and in departure from the grid street design, he featured

circular designs with radiating streets and diagonal boulevards to

provide vistas together with space for major public buildings. Sections

of the Bywater and Bayou St. John neighbourhoods were designed by Lafon.

Amongst his professional service consultancy were mapmaking, planning

the town of Donaldson in 1806 as well as surveying and advising for

upgrading the fortifications of New Orleans during the War of 1812 and

the Battle of New Orleans in 1815, which saw the end of English

aggression to subvert the young American colonies (Peoplepil, 2023).

Lafon had been recruited as an engineer for the US Army, being a Captain

in the 2nd Regiment of the US Militia of the Territory of Orleans,

preparing many maps for Governor Claiborne during the war.

Lafon was a man of diverse talents. In 1807, he published the first

almanac of New Orleans, “Calendrier de Commerce de la Nouvelle Orleans

Pour l’Annee 1807”, as well as “Annuaire Louisianais Pour l’Annee 1809”

(Edwards and Fandrich, 2018, p.12). Lafon’s contribution to the

redevelopment of New Orleans and the mapping of Louisiana was indeed

“extraordinary”, but his participation in the two wars waged against the

British on his home territory in 1812 and 1815 would seem to have been

overlooked when US President Andrew Jackson evaluated his courageous and

invaluable involvement in defeating a vastly superior (in number, at

least?) British war machine.

Figure 8: One of the earliest and most accurate

maps of Louisiana 1805 by Lafon – Carte Generale du Territoire d’Orleans

Comorenant Aussi la Floride Occidentale et une Portion du Territoire du

Mississippi.

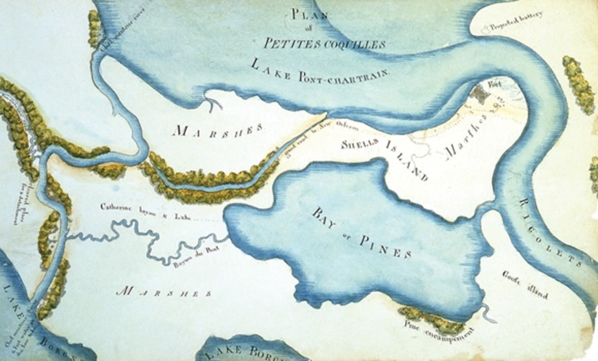

Figure 9: Map of the land around Fort Petites

Coquilles by Lafon, c. 1810 (Masson, 2012).

4. LAFON DURING THE BRITISH WARS AND AS A PIRATE

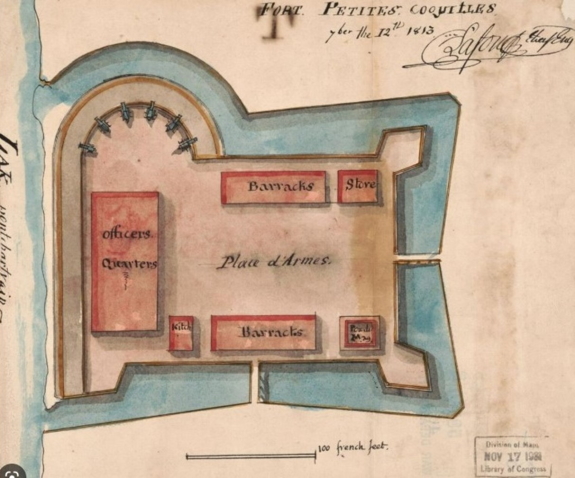

Promoted to Major in the US Militia Engineers, Lafon was able to

improve the defence capabilities at various forts around the territory,

inclusive of Petite Coquilles in 1813 (Figure 10 and Figure B5 in

Appendix B). Officially becoming the State of Louisiana in 1812, the US

became embroiled in the War of 1812 against the militant British Navy

who continually attacked American merchant ships, forcibly pressing

their crews into their own naval service.

Figure 10: Lafon 1813 plan of fortifications at

Petite Coquilles.

For years, Lafon had a close affiliation with the Laffite brothers,

Jean and Pierre Laffite, who called themselves Baratarian privateers,

operating from the island Barataria in the Gulf of Mexico (Figure 11).

It is quite likely that Lafon had early acquaintances with the pirating

brothers, possibly meeting in Bordeaux, France, before migrating across

the Atlantic to America, or even cooperating during the Haitian

rebellion when many French refugees from that country escaped to the

eastern US. Whenever the first contact was made, there is no doubt that

Lafon had been a close ally of the brothers for a number of years during

which time he plied the seas in his own privateering ship La Carmelita

upon which it is known that a number of liaisons between the three men

ensued. In August 1813, Lafon had the use of a vessel named La Misere,

which hijacked a prize called the Cometa. In 1814, Lafon participated in

an operation leading to the capture of two Spanish vessels, which was

followed by Lafon and others facing indictments for piracy (Guerin,

2010).

After the British had rid themselves of conflict against France, then

forcing Napoleon into exile, they deployed their efforts into razing

Washington DC, in August 1814. The principal target was then the capture

of New Orleans to gain control of the Mississippi River waterway. Facing

a British force of around 9,000 troops, US President/General Andrew

Jackson struck a deal with the leaders of the Baratarian pirate brigade

of some 1,200 individuals, to pardon the recently captured Jean and

Pierre Lafitte plus Lafon along with returning their vessels. Jackson’s

total force of some 5,200 men were able to incur substantial damage on

their opponents, with the British losing three Major Generals (including

Packenham) along with 2,033 soldiers, while only suffering less than 20

casualties (Edwards et al., 2019, p.61).

|

|

Figure 11: (Left) New Orleans privateer Jean

Lafitte, and (right) locality map of the pirate island Barataria in the

Gulf of Mexico which was the stronghold of the looting enterprise.

When the smoke cleared from this war-ending decisive rout, the

back-stabbing US President Jackson reneged on his pledge and held onto

the privateer ships and goods that had been confiscated on the earlier

raid on the pirate stronghold of Grand Terre. Although released from

prison, the two brothers and Lafon remained under close suspicion, and,

while still under US assault, they eventually fled New Orleans

completely (Edwards et al., 2019, p.62). The Lafitte brothers

re-established themselves on the island of Galveston in Texas, for good,

with Lafon joining them during their first two years of resettlement.

Before leaving the pirate stronghold in this new locality, Lafon

still acted as a surveyor for the Spanish government, measuring and

drafting the map “Entrada de la Bahia de Galveston”. He also surveyed

other regions in the southwest, at the same time acting as an official

spy for the Spanish. Duplicity seemed to be the norm for these

buccaneers of the high seas, as it is also firmly believed that Lafon

and the Lafitte brothers acted as double agents, supplying espionage

data to the US administration. The Mexican government in control of

Texas at the time reacted very forcibly when the colony of Mexican

patriots resident on the island conspired with the Lafitte brothers and

Lafon to raid some Spanish ships flying the Mexican flag. After Lafon

couriered a shipment of munitions to Galveston, his ship was seized on

the high seas by agents of the Galveston “government” (Edwards et al.,

2019, p.63).

5. BACK TO NEW ORLEANS IN 1818 AND FINAL DAYS

Having endured enough in Galveston, Lafon was back in New Orleans in

1818. His professional name in surveying and architecture had been

irreparably soiled through his association with the notorious pirate

brothers, his own privateering and the indictment for piracy handed down

by the New Orleans District Attorney, John Dick, in February 1815. After

this, he spent a short stint in gaol before he was finally acquitted

(Edwards et al., 2019, p.62).

Lafon’s choice of returning to New Orleans was more closely related

to his desire to be back with his lifelong love, Modeste Foucher, who

was a free woman of colour, and their four children (Edwards and

Fandrich, 2018, p.11). With minimal success in his attempt to reinstate

his professional career, Lafon attempted to sell all his possessions

with an ultimate desire to return to his homeland where his father and

brother still lived. Starved of work and destitute from Government

Internal Revenue Department fines and costs in defence of the lawsuits

demanding him to repay unpaid duties on the booty plundered from vessels

which were the victims of his daring privateering, Lafon found himself

in a whole world of despair. His halcyon days of brilliant chart making,

skilled surveying and stylish architectural design had deserted him. His

glorious dreams of sailing back to France with his coloured partner and

children, so that they could marry and be free of the discrimination

imposed upon them in the class-conscious New Orleans society, could not

be further away from being realised.

Just when it could not go downhill any further, a yellow fever

epidemic claimed him on 29 September 1820 at the modest age of 51 years.

He died in his home at No. 934-36 St. Louis Street in square 91,

originally purchased in 1804 from the estate of the wealthy woman of

colour, Julie “Betsy” Brion (Figure 12, who was the mother of Modeste

with Joseph Foucher) (Edwards and Fandrich, 2018, p.10). Lafon was

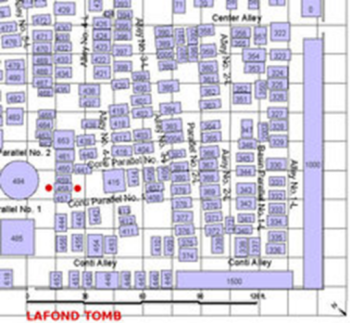

buried in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 (Figure 13 and Appendix C).

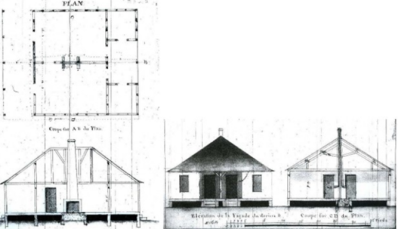

Figure 12: (Left) Lafon architectural plans for

one of his homes at Chef Menteur built in 1806, and (right) 1837

portrait of Julie “Betsy” Brion, from whose estate he bought the land

upon which he erected the house in which he passed away in 1820.

Figure 13: Barthelemy Lafon’s vault in St. Louis

Cemetery No.1 and its locality plan.

6. CONCLUDING REMARKS

The ultimate demise of Barthelemy Lafon from a man of distinction to

a penniless pirate are a sorry tale of riches to rags, finally played

out to the humiliation of his family members, making a fruitless most

lengthy journey from France in pursuit of what was believed to be a vast

estate of land holdings and other investments amounting to an Emperor’s

ransom. His father Pierre Lafon Snr. was in his mid-80s on the long trip

across the Atlantic, but most tragically died not long after his arrival

in 1822, stricken down by the same yellow fever, which had claimed his

son. Next to take the prolonged trip was Lafon’s older brother of 7

years, Pierre Lafon Jnr., accompanied by his 54-year-old wife Jeanne

Victoire. After a mere few days, Jeanne had died of the same deadly

disease, with her husband contracting the fatal fever to pass away in

the following month on 19 October 1822 at the age of 60. The last one

standing from the immediate family was the daughter of Pierre Jnr. and

Jeanne, the spirited Jeanne Philippe Lafon, who was Lafon’s niece. With

the obligatory post-humous inventory of Lafon’s estate the Court of

Probates listing a large portfolio of real estate, over 50 field slaves

and domestic servants, and a library of over 500 books, the extended

journey over the water appeared to offer a mighty inheritance for the

last member to risk death in the epidemic to claim her entitlement!

Pursuing the battle for Lafon’s estate to the Louisiana Supreme Court,

she eventually won, only to hear the court pronounce that the entirety

of Barthelemy Lafon’s estate “was wholly insolvent and unable to pay the

legacies and debts” (Edwards et al., 2019, p.66).

Thus, the fall of Barthelemy Lafon from reputable professional at the

top echelon of the community, to which he made so many invaluable

contributions both physically and financially, can only be the side

effects of his strong allegiance to the notorious plundering Lafitte

brothers, creating a rather unfavourable picture of his activities in

the dubious exploits of privateering, the polite name for condoned

piracy. Whatever image of disrepute may have been associated with Lafon

in his later years, there can be no doubt that his excellence in

surveying, mapping, engineering, architecture and town planning have

survived him, as the brilliance of his European garden design suburbs,

his many stylish and attractive buildings, practical restoration of

roads and flood levees and superb maps of New Orleans and Louisiana

stand in testimony to a complex character of early American history. He

was a hero of the Wars of 1812 and 1815, which saved his territory from

British domination, and his practical solutions with a sharp mind can

only be attributed to his professional training and experience as a land

surveyor.

REFERENCES

- Chamberlain C. and Farber L. (2014) Spanish Colonial Louisiana,

https://64parishes.org/entry/spanish-colonial-louisiana

(accessed Jan 2023).

- Cultural Landscape Foundation (2023) Barthelemy Lafon 1769-1820,

http://www.tclf.org/barthelemy-lafon (accessed Jan 2023).

- Edwards J.D. and Fandrich I. (2018) Surveys in early American

Louisiana: Barthelemy Lafon, Survey Book No. 3, 1804-1806, Report to

the Louisiana Division of Historic Preservation and the Masonic

Grand Lodge, Alexandria, Louisiana,

https://www.crt.state.la.us/Assets/OCD/hp/grants/NPShistoricfunding-2017/FY-2017-2018-Deliverables/Surveys%20in%20Early%20Louisiana%201804-1806%20Barthelemy%20Lafon.pdf

(accessed Jan 2023).

- Edwards J.D., Fandrich I. and Richardson G. (2019) Barthelemy

Lafon in New Orleans 1792-1820, Report to the Louisiana Division of

Historic Preservation,

https://www.crt.state.la.us/Assets/OCD/hp/grants/NPShistoricfunding-2019/Barthelemey%20Lafon%20in%20New%20Orleans_Final.pdf

(accessed Jan 2023).

- Guerin R.B. (2010) Notes on Barthelemy Lafon, Hancock County

Historical Society,

https://www.hancockcountyhistoricalsociety.com/history/notes-on-barthelemy-lafon

(accessed Jan 2023).

- Masson A. (2012) Barthélémy Lafon,

https://64parishes.org/entry/barthlmy-lafon (accessed Jan 2023).

- Peoplepil (2023) Barthelemy Lafon: French architect,

https://www.peoplepill.com/people/barthelemy-lafon (accessed Jan

2023).

- Rawat A. (2018) 10 interesting facts about the Louisiana

purchase of 1803,

https://learnodo-newtonic.com/louisiana-purchase-facts (accessed

Jan 2023).

- Reeves W.D. (2018) Notable New Orleanians: A tricentennial

tribute, Louisiana Historical Society,

https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/read/60393971/notable-new-orleanians-a-tricentennial-tribute

(accessed Jan 2023).

- State of Louisiana (2023) Important dates in history,

https://www.louisiana.gov/about-louisiana/important-dates-in-history

(accessed Jan 2023).

APPENDIX A: PLANS OF NEW ORLEANS

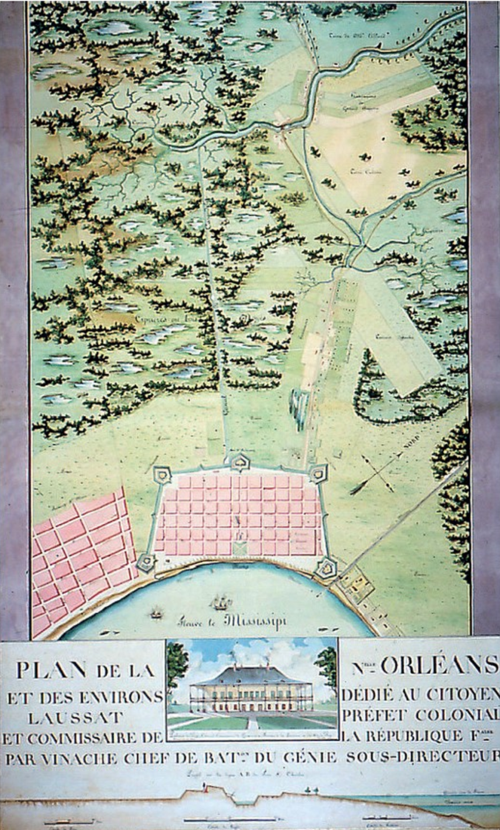

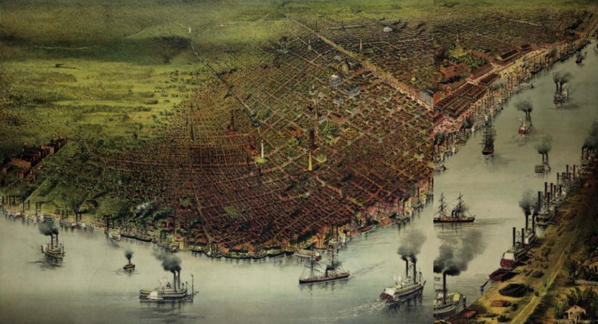

Figure A1: 1803 Vinache Plan De La Nouvelle

Orleans in celebration of France’s short reoccupation of the city before

the Louisiana Purchase Treaty was completed.

Figure A2: Plan of the easternmost section of

New Orleans by George H. Grandjean titled “Michoud Plantation”, being

the property of Alphonse Michoud comprising 36,056 acres. “B. Lafon” can

be seen printed on the left portion of the plan. Barthelemy Lafon had

gained ownership of this tract of land in 1801, which he used for what

was said to be a “brick plantation”. He lost this holding to creditors

in 1812.

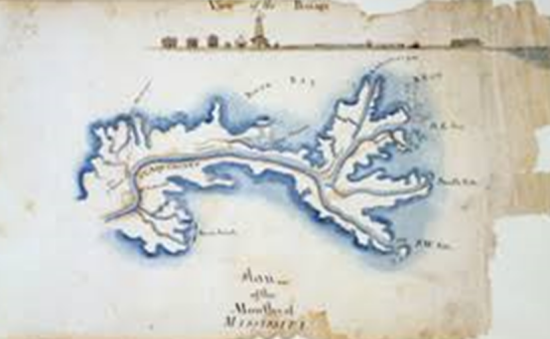

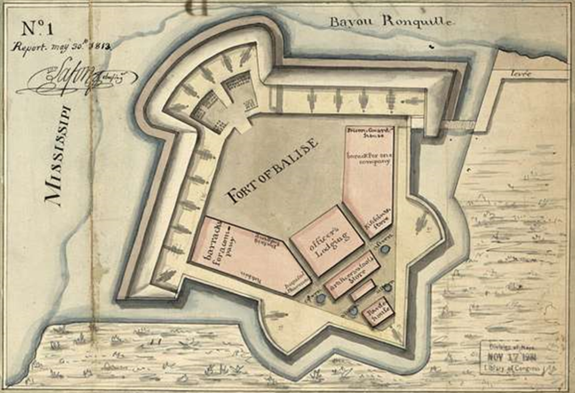

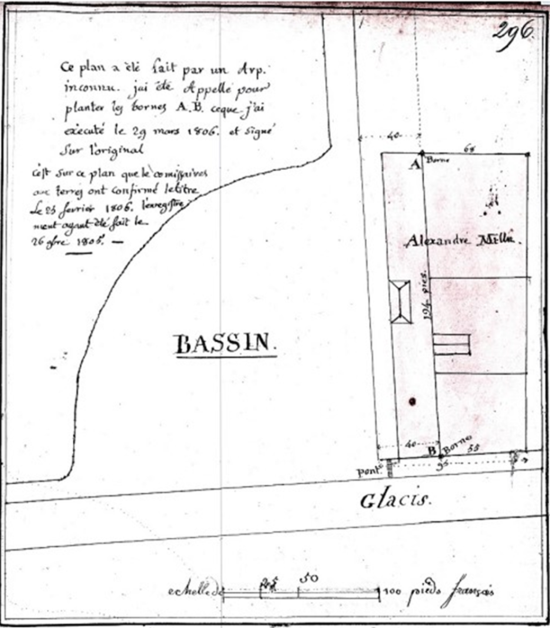

APPENDIX B: PLANS BY BARTHELEMY LAFON & LATER PERSPECTIVE VIEW

Figure B1: 1810 Lafon plan of the mouths of the

Mississippi River

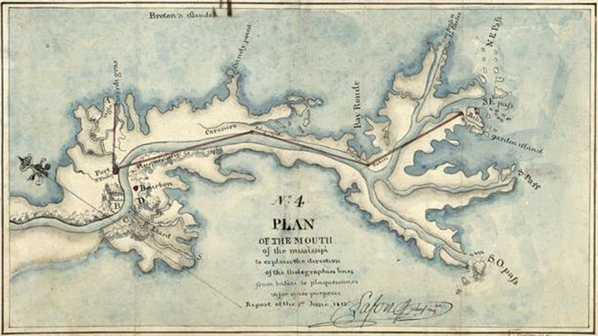

Figure B2: No. 4 plan of the mouth of the

Mississippi, June 1813.

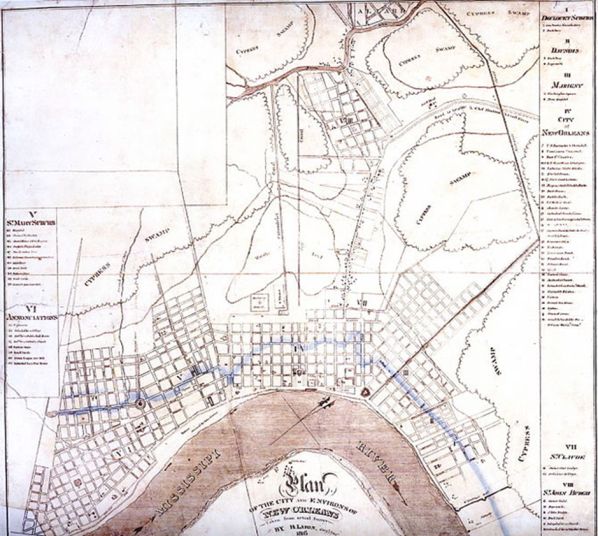

Figure B3: 1816 Lafon plan of the city and

environs of New Orleans.

Figure B4: Perspective view of New Orleans and

the Mississippi River from 1885.

Figure B5: Lafon plan of Fort Balise, 30 May

1813.

Figure B6: Lafon re-survey of the Carondolet

Canal turning basin and land of A. Milne, 29 March 1806

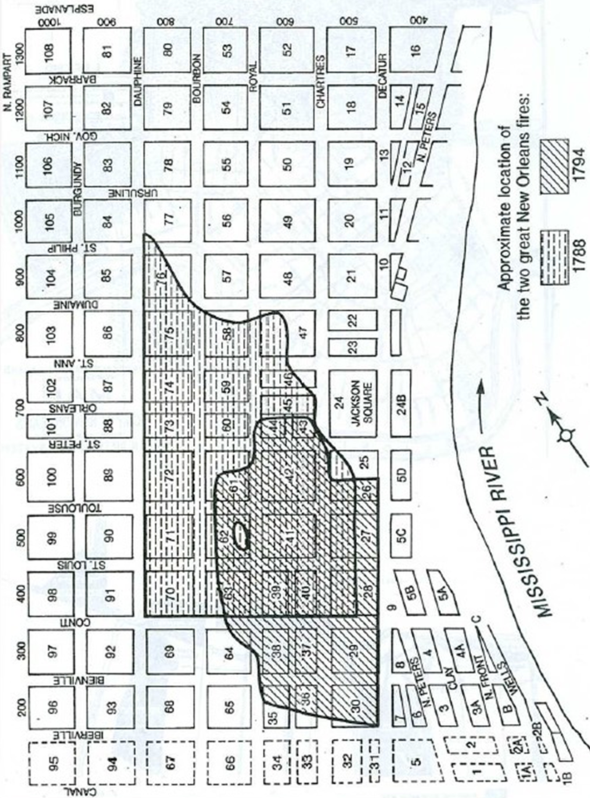

APPENDIX C: NEW ORLEANS MAP WITH STREET NAMES AND SQUARE SECTION

NUMBERS

Figure C1: The street pattern of New Orleans

City, showing street names and section numbers as allocated to the

locality descriptions for identification of property, with square 91

being where the house in which Lafon died in 1820 is situated.

Has the article inspired you to get to know more about USA?? Thejn

join us at the FIG Working Week 2023 which will take place in Orlando,

Florida. Read more at:

www.fig.net/fig2023