Article of the

Month - January 2021

|

A Global Survey of Reference Frame Competency

in terms of Education, Training and Capacity Building (ETCB): Results,

Analysis and Update

Ryan Keenan, Australia, Allison Craddock, United States, Mikael

Lilje, Sweden, Rob Sarib, Australia and Graeme Blick, New Zealand

|

|

|

|

|

| Ryan Keenan |

Allison Craddock |

Mikael Lilje |

Rob Sarib |

Graeme Blick |

This article in .pdf-format (22 pages)

SUMMARY

Geodetic infrastructure such as continually operating reference

stations are a vital component of reference frames around the world. As

such, a strong foundation of Education, Training and Capacity Building

is essential for ensuring geodetic infrastructure can be established,

maintained and operated correctly, also their data and information

outputs can be processed, analysed and interpreted correctly. In early

2018, the UN-GGIM Subcommittee on Geodesy sought to facilitate a

self-assessment of all member nations' sovereign capabilities to manage

and maintain reference frames. The Subcommittee's working group on

Education, Training and Capacity Building developed an online

Questionnaire seeking feedback specific to Reference Frame Competency.

Response to this survey so far, has been provided by ninety-eight

representatives of Member States and observers across the world. This

paper presents the results of this survey, and offers a brief analysis

of the findings, outlines a summary of the issues and identifies a

number of follow-on tasks for the UN-GGIM Subcommittee on Geodesy and

its working groups to consider when defining the scope of the

forthcoming Global Geodetic Centre of Excellence. Furthermore, linkages

to the Subcommittee on Geodesy Infrastructure Survey will be identified

when appropriate.

1. INTRODUCTION

The Need for a Global Geodetic Reference Frame

Geodesy is an important building block for sustainable development,

the administration and management of land as well as water and other

natural resources interests. Looking forward, geodesy also has the

potential to facilitate the critical access and alignment of the future

of smart societies and their digital economies; in short, geodesy is

playing an increasing role in the lives of people around the world, from

finding directions using a smart phone to alleviating poverty and

ensuring fresh water supplies. Because the Earth is in constant

motion, an accurate point of reference is needed in every country for

making measurements in the country. Geodesy provides a very

accurate and stable coordinate reference frame for the whole planet: a

Global Geodetic Reference Frame.

In February 2015, the United Nations (UN) General Assembly adopted

the resolution “A Global Geodetic Reference Frame for Sustainable

Development” – the first resolution recognizing the importance of a

globally-coordinated and supported approach to geodesy, involving all UN

Member States. Accordingly, the UN Global Geospatial Information

Management (GGIM) Subcommittee on Geodesy (SCoG) is working towards

developing an accurate and sustainable Global Geodetic Reference Frame

(GGRF).

The GGRF Roadmap states that the GGRF is “an authoritative,

reliable, highly accurate, and global spatial referencing

infrastructure. The GGRF includes the celestial and terrestrial

reference frame products and Earth Orientation Parameters (EOPs) that

connect them, the infrastructure used to create it, and the data,

analysis, and product generation systems. The GGRF also includes

gravimetric observations, products and height systems which underpin

measurements of elevation.”

The Subcommittee on Geodesy works within the guidance of the GGRF

Roadmap Implementation Plan and the position paper to define the

appropriate governance arrangements for the GGRF. In alignment with the

Roadmap structure, work is organised into five focus groups, with each

assigned one of the key issue categories of the Roadmap: geodetic

infrastructure; data sharing, policy, standards and conventions;

education, training and capacity building; communications and outreach;

and governance.

The Motivation of Reference Frame Competency

In preparation for the GGRF, the UN-GGIM SCoG sought, to facilitate a

self-assessment of all member nations' sovereign capabilities to manage

and maintain reference frames. The Education, Training, and Capacity

Building (ETCB) Working Group is one of five working groups currently

supporting the SCoG by acting on the Global Geodetic Reference Frame

Roadmap Implementation Plan. As a component of the UN GGIM Subcommittee

on Geodesy, the ETCB Working Group seeks to assess the current

availability of education, training, and capacity building resources,

identify gaps in capacity or other areas of need, and propose short- and

long-term solutions to realize the full scientific and social benefit of

the Global Geodetic Reference Frame. Wherever possible, elements of ETCB

work that are in support of the United Nations Sustainable Development

Goals and/or Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction are

identified.

The ETCB has developed a five-year strategy (see Appendix 1) with the

vision:

Member States have the capability to develop and maintain state

Global Geodetic Reference frames

and mission

The UNCCIM Working Group on Geodesy sub-committee on capacity

building will coordinate and facilitate capacity building with a

particular focus on regional needs and Member States with less capacity.

The ETCB is tasked with assisting UN Member States build their

capacity and expertise for the intuitive utilization and sustainable

worldwide development of the GGRF, and consequently this assessment

activity. It was hoped that the responses would provide sufficient

insights to determine and collate:

- Current competencies in Reference Frames (RF),

- Future competencies and special interests that are required, and

- Training needs of Member States.

Through its role to lead the development of the questionnaire, the

ECTB wanted to summarise how the audience perceived the capability of

their national geodetic survey organisation (GSO) or agency in terms of

defining, maintaining and operating their national geodetic reference

frame. Accordingly, the questionnaire was designed to assess

Member State RF competency requirements and educational needs, and

comprised of four Sections:

- Information about the Responder and their affiliation,

- Responder’s assessment of current and future RF competency

requirements of their Member State,

- Member State training needs, and

- Other information.

In considering the questionnaire, the ETCB recognised that UN Member

States would have different competency requirements and that all Member

States did not need to reach the same competency level. For example, a

small island state might be a user of the GGRF and thus need competency

in the use of GNSS and connection to the GGRF. A State providing

geodetic infrastructure to support the development of the GGRF might

need capability inVLBI and SLR etc. This led to the initial development

of a matrix defining four levels of RF competency requirements (ETCB,

2018), of which an updated version can be seen in Table 3. It was also

recognised that Member States would be at different levels in their

current skill rating. Another question posed was to consider if there

would be any regional differences in competency requirements, for

example were the requirements in a region of predominantly small island

nations be different from a continental region of Member States.

Given the global nature of the target audience, it was agreed that an

online questionnaire would be the most effective means of gathering

feedback from a geographically diverse target audience. The

Questionnaire was hosted on Google Sheets UN-GGIM SCoG ETCB

Questionnaire – Reference Frame Competency 2018/19

[1] in February 2018, and at time of writing (October 2019) was

still open for feedback after twenty-two months. For the purposes

of this paper, all those responses recorded at the end of October 2019

were included in this evaluation. Feedback from each section of

the questionnaire has been gathered, analysed and presented in summary

form with noteworthy findings and observations, along with a set of

initial proposals.

It must be mentioned that in August 2019, Member States of the

UN-GGIM commended the SCoG on the revised proposal to establish a global

geodetic centre of excellence (GGCE) under the auspices of the United

Nations to help address the critical gaps within the GGRF. The

objectives of the GGCE are to bring about:

- The development and sustainability of geodetic infrastructure

and analysis in Member States through enhanced global cooperation to

ensure an accurate, sustainable and accessible GGRF to which

regional and national Member State reference frames can be aligned.

- Making geodetic data Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and

Reusable (FAIR) so it can be shared globally and used to improve

decision making.

- Meeting Member State long-term geodesy training and capacity

development needs by assessing requirements and developing a

capacity building program based on UN Development Program (DP)

guidelines.

- Improved communications and outreach to describe why geodesy is

important, in particular to policy makers.

Given this development intention around the GGCE, it was clear that

feedback gathered by the ETCB would be extremely valuable in terms of

reflecting an objective large-scale survey of the current status quo of

RF competencies amongst UN Member States.

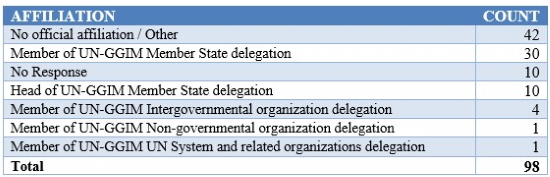

2. RESULTS – THE RESPONDENTS

This section provides information about the Respondents and their

affiliation. It was hoped to receive feedback from each Member

State’s UN-GGIM Head of Delegation, national agency representatives,

decision-makers, and geodetic community leaders in each State.

A total of ninety-eight responses were received from a total of

sixty-five Member States in the twenty-two months since the first

posting of the survey. The following figures show the country

location of each respondent, and the breakdown of the respondents in

terms of their organisation type, affiliation and role.

Figure 1 – Locations of the ninety-eight Respondents from sixty-five

Member States to the ETCB RF Competency Survey 2018/19

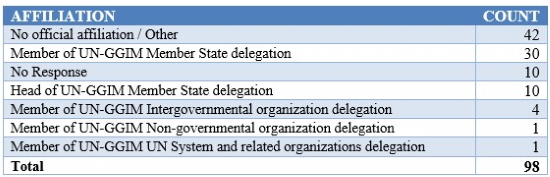

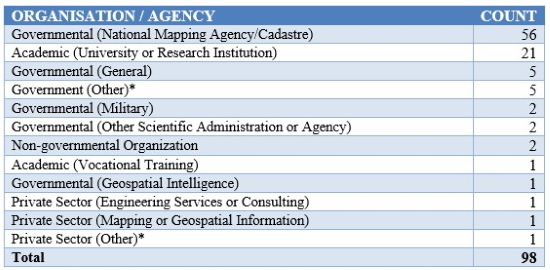

Table 1 – Breakdown of Respondents by

Affiliation

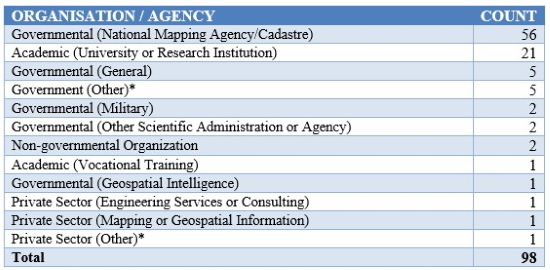

In terms of Affiliation, at least 46% were from UN-GGIM delegations.

Government agencies made up approximately 71% of identified respondents,

with 225 from academic organisations and just 3% from the private

sector.

Table 2 – Breakdown of Respondents by

Organisation / Agency Type

Respondents held a wide range of positions with a total of

seventy-eight different titles being provided, covering a comprehensive

range of experiences and responsibilities within their respective

organisations. Several countries were able to provide additional

feedback from multiple respondents, which helps to give more emphasis

and spread on the relevant competencies. Those countries were:

Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Brazil, Burkina Faso, France, India,

Italy, Mali, Marshall Islands, Philippines, Samoa, Senegal, Uganda and

Uruguay.

3. RESULTS – LEVELS OF REFERENCE FRAME COMPETENCY

This section covers the results for the Responders’ assessment of

current and future RF competency requirements of their Member State.

By assessing these, the ETCB expected to be suitably informed to focus

their efforts on helping build targeted training and developing

competency that will benefit each Member State, as well as filling

critical needs for the GGRF.

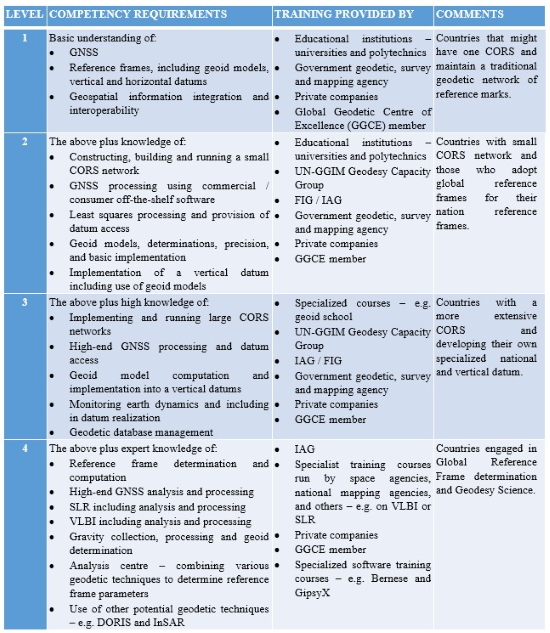

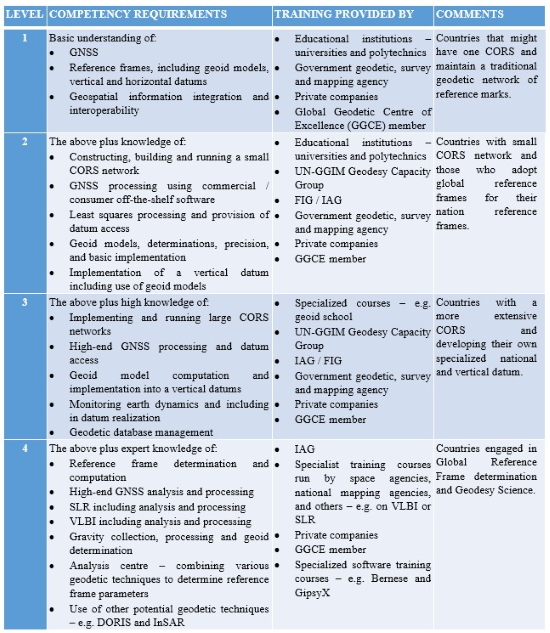

The following table shows the common competency requirements deemed

necessary for Reference Frames, categorised into four levels, with an

increasing level of competence, knowledge and know-how per level.

Note that this is an ‘evolving’ competency matrix based on questionnaire

responses, and national organisation status reports from around the

world.

This matrix provides GSOs with insight to descriptions of the skills,

experience and knowledge required to build and operate modern geospatial

reference systems and infrastructures (GRSI), along with training and

education requirements, and possible sources to provide the relevant

capability (Sarib, 2020).

Table 3 – Matrix of Predefined Levels of Reference Frame Competency

requirements (ETCB (2018))

Respondents were provided with this table for reference and invited

to evaluate the sovereign capabilities of their national GSO in terms of

defining, maintaining and operating their national geodetic reference

frame with respect to these levels. In some cases, the respondents

were self-evaluating, i.e. they were from the national mapping/geodetic

agency.

As mentioned earlier, it is worth stating that respondents have

different perceptions not only of the current RF competency level for

their GSO, but also their target level – both of which are highly

dependent on the size, location, topography and tectonic setting of

their Member State (cf. the geodetic requirements of a landlocked nation

on a stable plate might be quite different from a mountainous nation

spanning two tectonic plates).

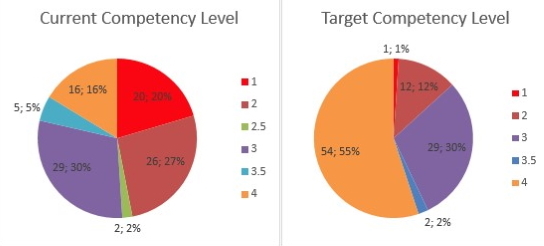

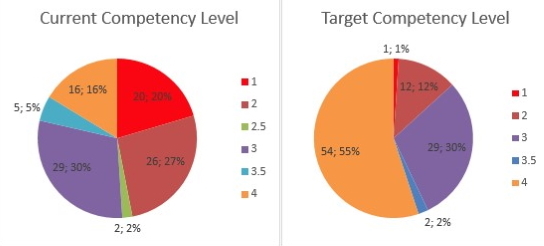

Figure 2 – Pie charts showing the Respondents' feedback on Current

Competency Level (left) and Target Competency Level (right)

Deriving simple statistics on the variances of these parameters, the

mean Current Competency Level is 2.5, and the mean Target Level is 3.4,

clearly suggesting that organisations want to “level up”.

Given the significant number of responses and feedback from developed

and developing nations, there was a considerable spread of ’status quo’

responses. In total, respondents felt that sixteen Member States had

already reached the appropriate level of Reference Frame competency and

required no additional specific training (other than ongoing retraining

and keeping up to date with emerging techniques and technologies). These

countries included: Australia, Argentina, Belgium, Brazil, Chile,

Germany, Finland, France, Hong Kong, Honduras, India, Italy, Japan,

Mali, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Slovenia, Slovakia, Sweden, UK

and USA. It is noted for several of these cumulative national responses,

that there were some variances in assessments of current and future

desired competency. For example, one State provided feedback from three

different respondents – two felt that a Level 4 competency had already

been attained, whereas the third respondent felt that Level 2 was a fair

estimate of both the current and target competency levels for State.

Similar levels of variability were seen across most nations for which

there were multiple respondents. One common takeaway from the majority

of all ninety-eight respondents, was that regardless of whether a higher

level of competency was aspired to or not, they would all have

challenges in maintaining their current and target competencies in all

relevant technologies and techniques as their organisations evolved,

taking into account the typical turnover of staff, budgeting cycles and

in several cases, political priorities. This will be covered more in the

next section.

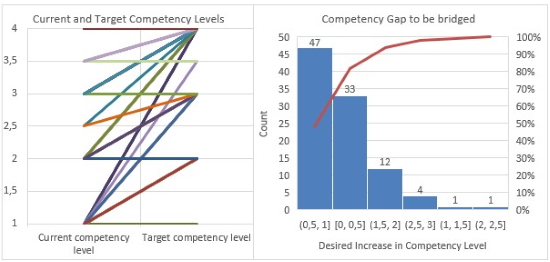

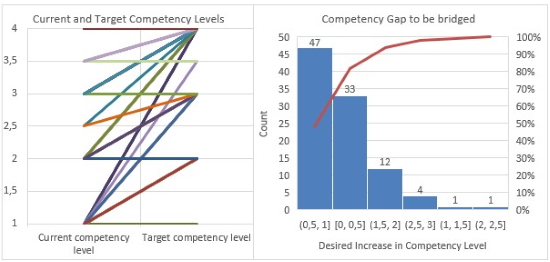

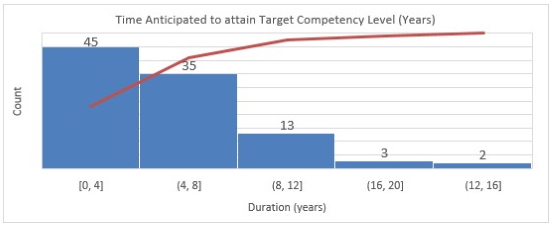

Figur 3 – Breakdown of Current and Future Competency Levels (left)

and Histogram quantifying the Gap in Competency Levels to be bridged

The feedback on Competency level evaluations highlights the

respondents’ subjective needs on how to raise their levels of RF

competency to their target level. An additional request for the

expected duration needed for this improvement was made to bridge the gap

between current and target competency levels, and the results grouped

into bins of four years.

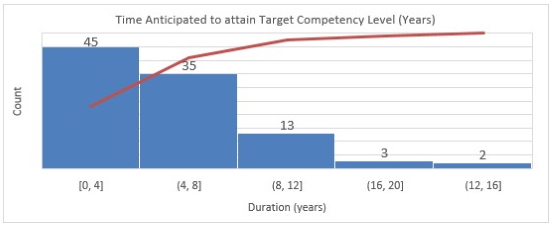

Figure 4 – Time Anticipated to attain Target Competency Level (Years)

One noteworthy observation on the anticipated duration of these

improvements is that the greatest improvement can be achieved within the

timeframe of four years, assuming resources and plans are delivered

successfully and on time. This should be duly noted for future

ETCB activities, by developing short well-defined agendas allowing

organisations to complete them swiftly whilst maintaining progress and

feeling a sense of achievement.

4. RESULTS – TRAINING NEEDS

The next section of the survey went into more detail about what the

respondents felt was required to be able to raise their competencies.

Based on the cumulative experience of the ETCB members who drafted the

survey, a choice of predefined requirements were offered to respondents

in the questions. The following four tables provide summaries of the

questions, their predefined selections and options, along with the

results.

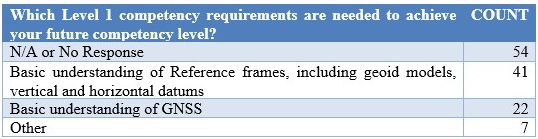

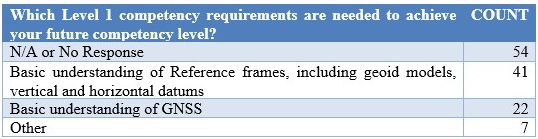

Table 4 – Feedback on Level 1 Competency Requirements

It is noteworthy that while twenty respondents ranked themselves as

being currently at Level 1, there were a larger number of responses for

training on basic understandings of GNSS and Reference Frames. It is

felt that this reflects the ongoing challenges to maintaining core

technical levels in existing and new departments given staff turnover

and personnel resourcing issues.

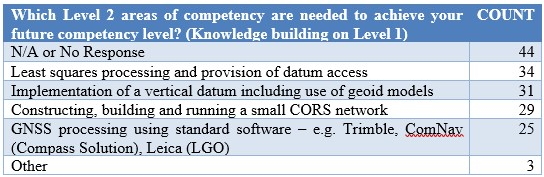

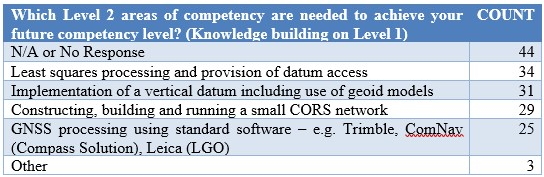

Table 5 – Feedback on Level 2 Competency Requirements

The general trends for required Level 2 competencies:

- A greater number of requests though for training around geoid

models and vertical datums – should be considered in the Proposals

section and by existing regional Capability Development Networks

(CDN) to arrange for additional workshops.

- Training on GNSS CORS networks and associated GNSS processing

software is a constant request.

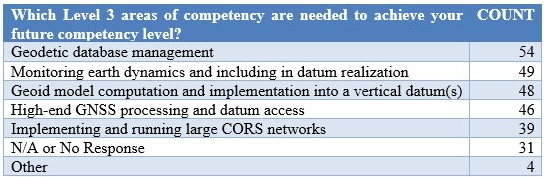

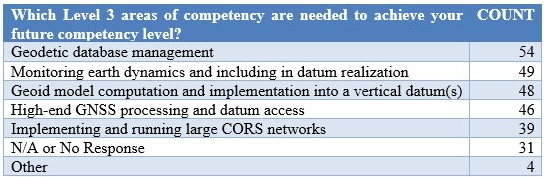

Table 6 – Feedback on Level 3 Competency Requirements

The general trends for required Level 3 competencies:

- More than half of respondents felt that the management of

geodetic databases is a necessary requirement and should be

considered in future workshops. There may be the possibility

to get the private sector involved with this.

- Training on GNSS CORS networks and associated GNSS processing

software is a constant request.A greater number of requests for

training around geoid models and vertical datums – should be

considered in the Proposals section and by existing regional CDNs to

arrange for additional Workshops.

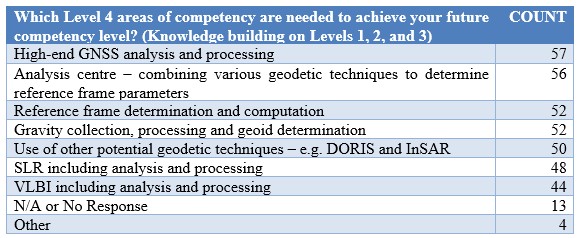

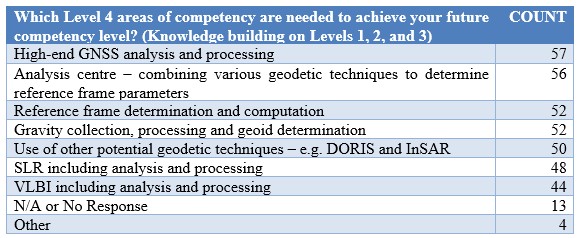

Table 7 – Feedback on Level 4 Competency Requirements

The general trends for required Level 4 competencies:

- Training on advanced GNSS analysis and processing is a constant

request, presumably as GNSS constellations evolve with additional

signals and new receiver technologies.

- Awareness about Analysis centres and their products is of

significant interest.

- A greater number of requests though for training around geoid

models and vertical datums – should be considered in the Proposals

section and by existing regional CDN to arrange for additional

Workshops.

5. FINDINGS.

This section affords a brief analysis of the findings, outlines a

summary of the main issues and identifies a number of follow-on tasks

for the SCoG and its working groups to consider when defining the scope

of the forthcoming GGCE.

Before providing the findings, it is necessary to state some caveats

about the survey results.

- Timing – the window for responding to this

survey was almost two years, so the status quo in some GSOs may have

changed during this time – hopefully for the better.

- Missing Responses – in the situation where

responses were not provided for sections in the questionnaire, the

term ’No Response’ has been included so that a correct statistical

proportion is given in the results.

- Competency Level Grading Subjectivity – these

are self-proclaimed competency evaluations, open to the subjectivity

of each respondent, their overall knowledge, awareness and

experiences, which may not have accurately reflected the true

situation of actual competency levels.

- Agency bias – the type of agency completing the

questionnaire may impact on the answers provided. This was

highlighted by the variation in responses from countries where

multiple responses were received from different agencies.

- Completion – there are a total of one-hundred

and ninety-five Member States, all with the need of GRF, however

this questionnaire was only answered by sixty-five Member States.

Greater participation in this (or a follow-on) survey may occur as

and when the future GGCE is announced.

CHALLENGES

A considerable number of noteworthy observations have been summarised

hereafter which provide a succinct insight of the global challenges

faced by respondents and their respective agencies. Further

details were afforded to the survey, however the essence of the most

common challenges have been distilled in the following sections.

Institutional challenges (typical but no limited to GSOs and

federal organisations)

- Lack of ability (experience / knowledge) and support within the

organisation to justify the establishment and on-going maintenance

of geodetic infrastructure and system.

- No specific and credible mechanisms and frameworks to enable the

sharing of technical knowledge and to support training on the

various aspects of the geodetic data /information cycle

- Lack of categorization of existing technical knowledge and other

resources that may enable intuitive and interoperable use

- The desire to immediately establish a reference frame rather

than learn how to do it; dur to a lack of resources and capability

leading to outsourcing as the preferred option

- Unaware how to and whom to contact in various UN and

international organisations

- Lack of understanding of the strategy, approach, and

requirements to accessing (or even becoming) a regional data

repository or analysis centre

Capacity Building / Training and Education challenges

- The most appropriate person(s) from agency are not always

selected / invited to attend relevant training / workshops etc

- There is often no follow-up or implementation support for those

staff who have attended the appropriate training / capacity

development programs

- There are many “experts or specialists” available to provide

training on core competencies but no system to access or support the

“trainers / educators”

- Many CDN are staffed by international experts volunteering their

assistance beyond their current role, and thus their ongoing

availability is due to the good will of their employer which can be

limited/restricted or unreliable

Barriers to increasing Competencies

- Lack of resources including:

- budget (fiscal and personnel allocation)

- equipment, software, geodetic and supporting infrastructure

(i.e. power, communications)

- socio-political support

- Lack of people with sufficient knowledge, qualifications and

skills, and little consideration of succession planning

- Lack of access to specialists or experts or supervisors in

geodetic surveying

- Lack of training and educational institutes and facilities

- Lack of policies and legislative basis, effecting lack of

support from politicians and decision makers

- Challenges due to multiple open data standards and the

unreliable interoperability of geodetic data globally especially

when GSOs’ core competencies are so different

- Lack of appropriate material to advocate the importance,

achievements and support the justification of modernised GRSI (i.e.

return on investment analysis and statistics, case studies) to suit

the target audience

SOLUTIONS

The following section comprises of direct feedback submitted to the

survey and possible solutions as derived by the authors during analysis.

What training will help the RF competency needs of agencies?

- Improved tertiary education on the fundamentals of surveying

i.e. competencies prior to Level 1

- Increased Level 1 and Level 2 training on geodetic theory and

implementation:

- Determination and computation of Reference Frame parameters;

Height unification and modernisation; Geoid determination;

Network adjustments; Transformation parameters derivation

- Geodetic data management fundamentals and planning

- Clear statement of the requirements to becoming a regional data

repository or analysis centre; and understanding the operations,

services and products

- Establishing, operating and maintaining a GNSS CORS network

- Understanding the techniques / measurements from GNSS, VLBI,

SLR, DORIS, Gravity and InSAR

- Monitoring and measuring the dynamics and deformation of the

earth; dynamic reference frames and datums; implications and

applications; time dependent calculations and models

Resources and Resourcing solutions

- More resourcing, investment, training, scholarships, grants etc.

from internal and external sources – preferably facilitated from a

“centralised” group

- Awareness of funding options and mechanisms – what are they, how

to access, understanding the eligibility criteria and requirements,

and the process to apply

- Succession planning for personnel resources in addition to

regular participation in regional CDN events and workshops

Training and Education solutions

- Increased frequency of regional training to attain a consistent

approach and community spirit

- Consider information exchange seminars on new technologies,

applications and systems that affect GNSS, geodesy and positioning

- Greater recognition and advocacy of geodesy and its benefits to

stakeholders and community

- Courses during the non-academic periods i.e. “summer schools”,

workshops (such as UNOOSA, IAG etc.)

- Make available, easily discoverable, intuitively usable, and

interchangeable training and reference materials, via online

platforms

- Sustainable ways to bridge the knowledge gap and digital divide,

especially in developing countries and/or countries in transitio

- Strategies to encourage more support / effort / assistance from

those geodetic organisations at Level 3 and 4

- Better coordination by the agencies who have possess the

required “levels” and global / regional bodies and global

organisations (i.e. FIG, IAG, UNOOSA et al.)

Sharing and Collaboration solutions

- Share and exchange both resources and data across borders where

possible

- More capacity development to improve sharing of geodetic data –

specifically workshops on the advocating the benefits of sharing,

and development of relevant policy to support implementation

- Develop pathways, structures, frameworks and roadmaps which

facilitates greater collaboration amongst member countries, academic

institutions (including the scientific and research community) and

the commercial sector, to deliver pragmatic and fit-for-purpose

solutions

- Facilitate greater collaboration and engagement, and investigate

alternate sources of resources, in particular the private sector and

independent experts who can assist

Increased Regional Involvements

There are several examples where ongoing regional initiatives have

demonstrated moderate success. One such example is how the FIG

Asia Pacific Capability Development Network (FIG AP CDN) and its

enduring collaboration with the ETCB in Asia and the Pacific region.

Participants from these groups have run and contributed to a significant

number of successful reference frame in practice workshops since 2013,

helping to:

- Provide advice on the importance of strategic and operational

planning to develop geodetic and geospatial communities, in this

instance across Pacific Island Country Territories (PICTs).

- Advocated the role and value of geodetic and geospatial

information to resolving and managing the impacts of climate change

/ sea level rise, and natural disasters such as cyclones,

earthquakes and tsunamis.

A significant /common theme for workshops run by AP CDN is into the

education, planning and maintenance of GNSS CORS infrastructure

capability and geodetic datum modernisation activities.

International Federation of Surveyors (FIG) Commission 5 has a

well-known and industry recognised workshop entitled ‘Reference Frames

in Practice (RFIP)’ that has been run numerous times alongside

conferences, workshops and other geospatial events, not only those

organised by FIG. Further information on the FIG AP CDN and its

involvement can be found at

https://www.fig.net/news/news_2019/11_ap_cdn.asp

One further observation was that most organisations would benefit

from receiving an independent holistic evaluation of their current

competencies with specific objective focus on achieving their target

competencies with respect to their strategic roadmap and vision.

6. SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Based on the collective analysis and weighting of survey responses,

there are four significant points that must be considered to

successfully build capacity for the GGRF:

- There is a very strong interest or need to continue to build

capacity for geodetic reference frame competency, especially in

those developing countries with limited resources.

- There is a very strong argument for continued contribution of

developed countries to support these developing countries at the

global, regional and national level.

- There is an increasing demand for a global facilitator of ETCB

to help collate requests, arrange resources such as trainings,

in-country workshops, technical reviews etc. This entity

should also be responsible for ensuring stronger coordination and

sustainable collaboration between those existing

groups/organisations who currently provide these resources and could

do so in the future.

- Finally, this survey generated considerable objective feedback

and insight for those forming the GGCE, its structural organisation,

its objectives and the obligations that it must assume for it to

truly deliver benefit and sustainable long-term impact.

The overall challenge for geodetic organisations is to ensure that

priority capacity building commences and becomes continuous; to do so,

the following recommendations are given.

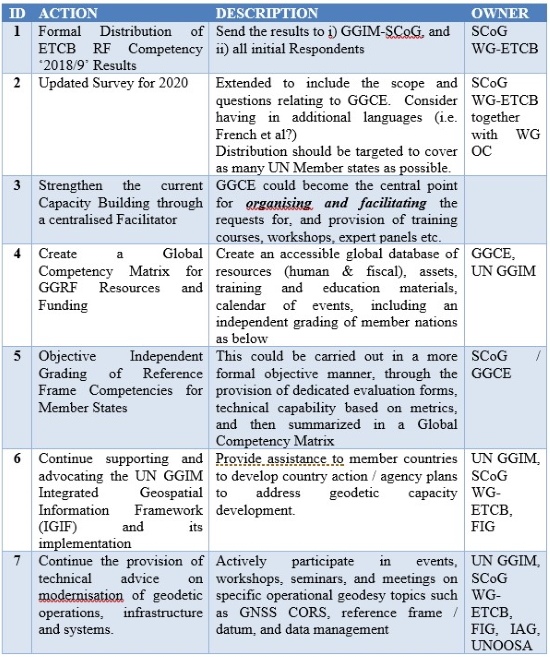

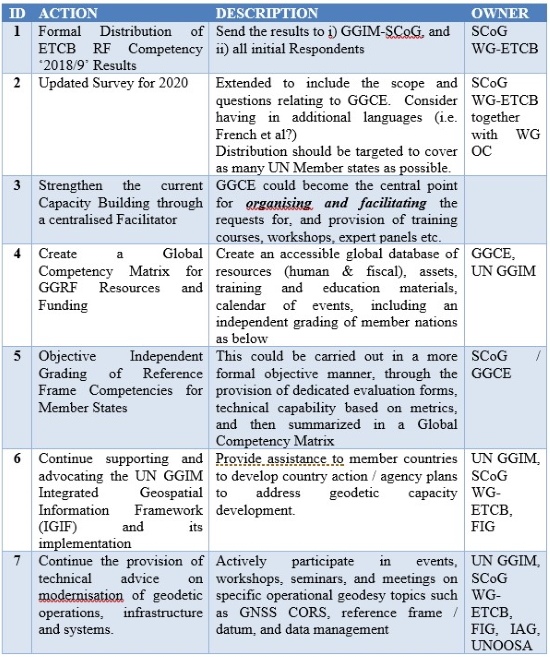

RECOMMENDATIONS

Table 8 – Recommendations for ongoing ETCB activities on raising the

level of Global Reference Frames Competency

The UN-GGIM SCoG, together with the global geodetic community, can

overcome the common challenges and accelerate to higher levels of RF

competency by facilitating the necessary mix of training, exposure,

collaboration and knowledge transfer.

As quoted earlier during one of the objectives for the GGCE - ‘Making

geodetic data Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable (FAIR)

…’; the authors feel that the GGCE should ensure that training and

education be treated in a similar manner with the following objective:

- Making education, training and capacity building Findable,

Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable (FAIR) so it can be shared

globally and used to improve decision making.

Ultimately, the successful establishment of the GGCE as proposed by

the UN-GGIM SCoG would be best positioned to deliver, implement and

facilitate an enhanced, fit-for-purpose and globally sustainable

capacity building initiative for ongoing GGRF education and

training.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the following:

- Those involved with drafting and defining this questionnaire in

early 2018, with notable thanks going to Allison Craddock and Graeme

Blick, for their efforts on driving the initial questionnaire’s

delivery and creating the initial four-level competency matrix

respectively,

- Respondents for their time, constructive feedback and

contribution to the survey, and'

- Groups involved with UN-GGIM SCoG working to realise the vision

of the GGCE.

REFERENCES

ETCB (2018), Reference Frame Competency Survey [online at Google

Documents], Available at:

https://docs.google.com/forms/d/128LHyUCYsXRn9hQSdtGGa54XniAVPRjeRws3e0Dva9o/viewform?ts=5d9e42bf&edit_requested=true

[Accessed 10 Jan 2020].

FIG Asia Pacific Capacity Development Network – Reports &

Presentations [online] Available at:

http://www.fig.net/organisation/networks/capacity_development/asia_pacific/index.asp

[Accessed 10 Jan 2020].

Global Geodetic Reference Frame [online] Available at:

http://www.unggrf.org/ [Accessed 10

Jan 2020].

GGRF Roadmap Annex 1, Glossary of Terms [online], Available at:

http://ggim.un.org/meetings/GGIM-committee/documents/GGIM6/E-C20-2016-4%20Global%20Geodetic%20Reference%20Frame%20Report.pdf

[Accessed 10 Jan 2020].

Sarib, R (2020) “Capacity Development Program for a Modernised

Geodetic Framework”. Proceedings FIG Working Week, Amsterdam, The

Netherlands.

United Nations Global Geospatial Information – Subcommittee on

Geodesy [online] Available at:

http://ggim.un.org/UNGGIM-wg1/

[Accessed 31 Dec 2019]

United Nations Global Geospatial Information – Subcommittee on

Geodesy Newsletter #10 November 2019 ‘Global Geodetic Centre of

Excellence (GGCE) – A new benchmark for global geodesy’ [online],

Available at:

https://www.unggrf.org/UN-GGIM_Newsletter_10-2019.pdf [Accessed 10

Jan 2020]

UN GGIM (2018a), “Integrated Geospatial Information Framework - A

Strategic Guide to Develop and Strengthen National Geospatial

Information Management Part 1: Overarching Strategic Framework”, United

Nations Global Geospatial Information Management.

UN GGIM (2018b), “Integrated Geospatial Information Framework - A

Strategic Guide to Develop and Strengthen National Geospatial

Information Management Part 2: Implementation Guide”, United Nations

Global Geospatial Information Management.

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Dr. Ryan KEENAN, since completing his PhD in GPS,

Geodesy & Navigation (University College London), Ryan has over twenty

years of GNSS positioning industry experience initially with specific

focus on high-precision applications for the survey, geodesy, machine

control, agriculture and mining sectors. More recently, in his

role as Principal Consultant at Positioning Insights, Ryan has been

providing independent advice on location technologies to governments and

numerous SMEs across the Asia Pacific and Oceania regions. Dr.

Keenan is currently co-Chair of FIG Commission 5’s Working Group 4 on

‘GNSS’, a member of the FIG Asia Pacific Capacity Development Network

and member of two UN GGIM Subcommittee on Geodesy Working Groups –

Education, Training and Capacity Building, and Outreach & Communication.

Allison CRADDOCK is a member of the Geodynamics and

Space Geodesy Group in the Tracking Systems and Applications Section at

the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, USA. She is

the director of the International GNSS Service (IGS) Central Bureau,

manager of external relations for the International Association of

Geodesy’s Global Geodetic Observing System and staff member of the NASA

Space Geodesy Program.

Mikael LILJE, Manager of International Department at

Lantmäteriet (the Swedish mapping, cadastral and land registration

authority). Mikael has been working at Lantmäteriet since 1994

mainly at the Geodetic Infrastructure Department where he was the

manager between 2009 and 2019. In his current position he is responsible

for the international services that Lantmäteriet is involved in, mainly

in Africa and Eastern Europe. He is also supporting Lantmäteriet’s

management team with international cooperation on UN, Global, European

and Nordic level. Mikael is currently leading the Working Group on

Education, Training and Capacity Building within the UN GGIM Sub

Committee on Geodesy. Mr. Lilje has been an active member of the

FIG since 1998 and is now FIG vice President.

Rob SARIB, Director Survey / Surveyor-General, in

the Land Information Group of the Northern Territory Government of

Australia’s Department of Infrastructure Planning and Logistics. Rob

Sarib obtained degree in Bachelor Applied Science – Survey and Mapping

from Curtin University of Technology Western Australia in 1989. He also

holds a Graduate Certificate in Public Sector Management received from

the Flinders University of South Australia. Rob was registered to

practice as a Licensed Surveyor in the Northern Territory, Australia in

1991. Since then he has worked as a cadastral and geodetic surveyor, and

a land survey administrator. Mr. Sarib has been an active member of the

FIG since 2002, and is now Chair of the FIG Asia Pacific Capacity

Development Network. He is presently a Board member of Surveying and

Spatial Sciences Institute; the Chair of the Surveyors Board of Northern

Territory; and member of the Inter-governmental Committee on Survey and

Mapping – Australia.

Graeme BLICK obtained his Bachelor of Surveying from

Otago University in 1980. He worked for GNS Science before

spending time at the University NAVSTAR Consortium in Boulder Colorado

utilising GPS to monitor crustal movements on several international

projects. In 1995 he moved to Land Information New Zealand (LINZ),

New Zealand’s National Survey and Mapping agency. He is the Chief

Geodesist and Group Manager of the Positioning and Resilience Group

where he continues to work on and manage the development and

implementation of the geodetic system in New Zealand and develop a new

resilience programme of work for LINZ.

CONTACTS

Dr. Ryan KEENAN

Positioning Insights

Melbourne, Victoria

AUSTRALIA

Tel. +61-476-688-117

Web site:

www.positioninginsights.com.au

Ms. Allison CRADDOCK

NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory

4800 Oak Grove Drive, MS 238-600

Pasadena, CA 91109

USA

Mobile: +1 818 237 0425

Web site: www.jpl.nasa.gov

Mr. Mikael LILJE

LANTMÄTERIET – International Department

801 82 Gävle

SWEDEN

Tel: +46-026-63 37 42 | Mob: +46 70 2089571

Web site:

www.linked.com/company/lantmateriet |

www.facebook.com/lantmateriet

Mr. Rob SARIB

Department of Infrastructure Planning and Logistics

GPO Box 1680

Darwin NT

AUSTRALIA

Tel. +61 8 8995 5360

Web site: https://dipl.nt.gov.au/

Mr. Graeme BLICK

Land Information New Zealand

PO Box 5501

Wellington 6145

NERW ZEALAND

Tel. +64 27 4528769

Web site: https://linz.govt.nz