Article of the Month -

November 2006

|

World Bank Support for Land Administration and Management: Responding to the

Challenges of the Millennium Development Goals

Mr. Keith Clifford BELL, World Bank

This article in .pdf-format.

This article in .pdf-format.

1) This paper is written and presented at the XXIII FIG Congress in

Munich, Germany, 8-13 October 2006.

Keywords: good governance, land administration, land management,

land policy, land reform, Millennium Development Goals, tenure security,

World Bank.

SUMMARY

Land and property are generally the major assets in any economy. In most

countries, land may account for between half to three-quarters of national

wealth. Land is a fundamental factor for agricultural production and is thus

directly linked to food security. Security of land tenure is an important

foundation for economic development, social and environmental management,

and also for supporting reconstruction following a disaster or conflict.

There are many complexities, dimensions and themes associated with land

administration and management. Securing land rights is particularly relevant

to vulnerable groups such as the poor, women, orphans, displaced persons and

ethnic minority groups. Fees and taxes on land are often a significant

source of government revenue, particularly at the local level. In most

societies, there are many competing demands on land including development,

agriculture, pasture, forestry, industry, infrastructure, urbanization,

biodiversity, customary rights, ecological and environmental protection.

Many countries have great difficulty in balancing the needs of these

competing demands. Land continues to be a cause of social, ethnic, cultural

and religious conflict. For many centuries, many wars and revolutions have

been fought over rights to land. Throughout history, virtually all

civilizations have devoted considerable efforts to defining rights to land

and in establishing institutions to administer these rights, i.e. land

administration systems.

Reform of land administration in any country is a long-term prospect

requiring decades of sustained commitment. It is a major investment of

capital and human resources and requires strong and consistent leadership in

order to achieve effective, sustainable outcomes. The World Bank, with the

support of development partners and civil society organizations, are

continuing to support land projects throughout the world. These projects

have had varying emphases on social equity and economic development. In

post-conflict countries, tenure security and access to land are major

factors in providing long-term stability.

This paper outlines the World Bank’s support for land reform programs to

meet the challenges of the Millennium Development Goals (MDG), and presents

the reconstruction of land and property rights in Aceh, Indonesia, as a

special case study.

1. INTRODUCTION

Reform of land administration in any country is a long-term prospect

requiring decades of sustained commitment. It is a major investment of

capital and human resources and requires strong, consistent, transparent and

accountable leadership, in order to achieve effective, sustainable outcomes.

The World Bank, with the support of development partners and civil society

organizations, are continuing to support, land projects throughout the

world. These projects have varying degrees of emphasis on social equity and

economic development. In post-conflict countries, tenure security and access

to land are major factors in providing long-term stability.

2. THE IMPORTANCE OF LAND

Land and property are generally the major assets in any economy. In most

countries, land accounts for between half to three-quarters of national

wealth. Land is a fundamental factor for agriculture production and is thus

directly linked to food security. Over the past two decades, much has been

written about land being one of the main sources of collateral, used to

obtain credit from established financial institutions such as banks, as well

as from informal providers of credit.

Former United States President, Mr. Bill Clinton, who now serves as the

United Nations (UN) Special Envoy for Tsunami Recovery, following his first

visit to Aceh, on May 23, 2005, advised:

I can think of nothing that will generate more income over the long

run for average families in this region than actually having title to the

land they own. Then, they will be able to borrow money and build a much

more diversified, much more modern economy.

On July 14, 2005, Mr. Clinton presented his first report on Aceh to the

UN Economic and Social Council, (ECOSOC) in New York City, and advised:

Those of you familiar with the work of Mr. (Hernando) de Soto around

the world and similar projects know that the world’s poor people have

roughly 5 trillion dollars in assets that are totally unusable for

economic growth because they don’t have title to them so they can’t get

credit using what they own as collateral. This is going to be done through

the World Bank grant in Aceh. It is very forward thinking on both the part

of the World Bank and Indonesia but I hope that the other countries

affected will do that and in its pursuit of the Millennium Development

Goals, I hope that you, Mr. President and ECOSOC, can have an influence in

urging this sort of project to be done in other countries outside the

tsunami affected areas.

Security of tenure is an important foundation for social and economic

development. Fees and taxes on land are often a significant source of

government revenue, particularly at the local level. Securing land rights is

particularly relevant to vulnerable groups such as the poor, women and

indigenous groups. In most societies, there are many competing demands on

land including development, agriculture, pasture, forestry, industry,

infrastructure, urbanization, biodiversity, customary rights, ecological and

environmental protection. Many countries have great difficulty in balancing

the needs of these competing demands. Land has been a cause of social,

ethnic, cultural and religious conflict and many wars and revolutions have

been fought over rights to land. Throughout history, virtually all

civilizations have devoted considerable efforts to defining rights to land

and in establishing institutions to administer these rights – land

administration systems.

3. THE MILLENNIUM DEVELOPMENT GOALS

The Millennium Development Goals (MDG) commit the international community

to an expanded vision for development, one that vigorously promotes human

development as the key to sustaining social and economic progress in all

countries, and recognizes the importance of creating a global partnership

for development. The goals have been commonly accepted as a framework for

measuring development progress. The MDG constructively challenges the entire

global community. On the one hand, the MDG challenge poor countries to

demonstrate good governance and commitment to poverty reduction. On the

other hand the MDG also challenge the more wealthy countries to maintain

their commitment to support economic and social development (World Bank

2002).

Many of the targets of the MDGs were first set out by international

conferences and summits held during the 1990s. They were later compiled and

became known as the International Development Goals. In September 2000 the

member states of the United Nations unanimously adopted the Millennium

Declaration (UN, 2000). Following consultations among international

agencies, including the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF),

the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and the

specialized agencies of the United Nations, the General Assembly recognized

the MDG as part of the roadmap for implementing the Millennium Declaration.

The eight MDG are:

- Goal 1: Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger

- Goal 2. Achieve universal primary education

- Goal 3 Promote gender equality and empower women

- Goal 4 Reduce child mortality

- Goal 5 Improve maternal health

- Goal 6 Combat HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases

- Goal 7 Ensure environmental sustainability

- Goal 8 Develop a global partnership for development

To monitor progress with implementation of eight MDG are 18 output

targets and 48 key performance indicators. World Bank support for land

reform projects is directly aligned to the MDGs, and especially with MDGs 1,

7 and 8. Indicator 32, which is used to monitor MDG 7 (Ensure environmental

sustainability), specifically refers to tenure security. Perhaps MDG 3

(Promote gender equality and empower women) could be enhanced if there was

an inclusion of an indicator to monitor women’s property rights. Issues such

as poverty reduction, tenure security, pro-poor land management, good

governance, environmental sustainability, gender equality, the rights of

vulnerable groups in society, exploitation of information communication

technology (ICT) are all key issues for land administration and management

programs.

There is no doubt that professional land surveyors and other land-related

professionals can contribute to the MDG. Many such professionals provide

technical support to the World Bank and its development partners. Therefore,

it is very timely that the International Federation of Surveyors (FIG) is

proposing to establish a special task force that will bring together

expertise to analyze, explain, and present a FIG response to the MDG

(Enemark, 2006). It is understood that the proposed task force would

endeavor to cooperate with UN agencies, and the World Bank, to develop the

FIG strategy, and to advise the FIG Council on necessary actions. Perhaps

consideration could also be given to a review of FIG’s most pre-eminent

publication “Cadastre 2014” (1998), which pre-dates the MDG.

4. OVERVIEW OF WORLD BANK SUPPORT TO LAND SECTOR

The World Bank has been directly engaged in supporting the land sector

for more than thirty years. This work can be broadly divided into key areas:

(i) support for policy development, (ii) analytical and advisory (AAA)

research; (iii) investment lending to support development and reconstruction

(or lending). Land issues are deeply rooted in countries’ histories and are

often sensitive politically, implying that attempts to address them need to

be solidly grounded in empirical research, often building on carefully

evaluated pilots. The Bank’s strong analytical capacity and intellectual

leadership have allowed operations to draw on cutting edge research to show

the importance of land issues for overall economic development and to help

countries formulate and build consensus around national strategies to deal

with land in a prioritized and well-sequenced manner. In many cases, e.g.

China, Mexico, Ethiopia, India, South Africa, and Brazil, demand for the

Bank’s analytical work is equal or greater than that for Bank lending for

land projects. Strong links to academic and civil society institutions in

client countries and with development partners, continue to allow the Bank

to translate analytical inputs into effective solutions to support

development and reconstruction.

On the lending side, generally, Bank-funded land projects seek to

alleviate poverty and enhance economic growth by improving the security of

land tenure and efficiency of land markets through the development of an

efficient system of land titling and administration that is based on clear

and consistent policies and laws, gender-responsive and supported by an

appropriate institutional structure. Lending projects typically involve: (i)

legal, regulatory and policy reform; (ii) institutional reform; (iii)

systematic land registration (first time titling); (iv) support for

on-demand titling and development of subsequent land transactions; (v) land

valuation; (vi) improved service delivery for land agencies; and (vii)

capacity building for government, private sector and academe (Bell, 2005).

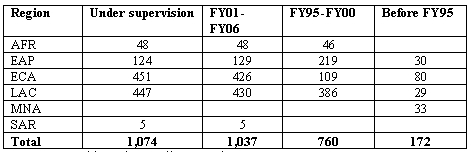

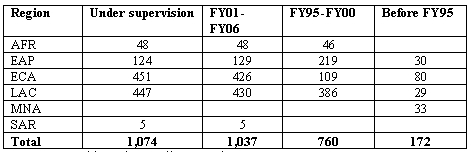

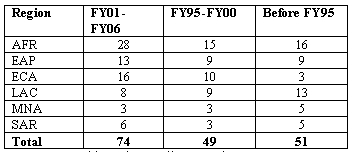

Table 1 displays total World Bank lending for land administration by

fiscal year (FY) and region. It highlights a significant, though regionally

highly uneven, increase in total lending with the total amount of lending

under supervision currently standing at $1.1 billion. Total commitments in

FY01-06 were above $1 billion, compared to $760 million in FY95-00, and only

$172 million before FY95. However, the regional distribution is not uniform,

with two regions, Europe and Central Asia Region (ECA) and Latin America and

Caribbean Region (LAC), making up almost 90% of the size of the portfolio,

followed by East Asia and Pacific Region (EAP), and virtually no lending in

Africa (AFR), South Asia Region (SAR), and Middle East North Africa Region

(MNA). One of the key reasons for such a vast difference is that the

background work needed to underpin land administration projects in the MNA

has really only just started. Given the importance of land policy for a wide

range of situations, plus the Bank’s shift from project- towards

policy-based lending, it is not surprising to find an increasing number of

projects with land policy or administration components.

Table 1: Lending for dedicated land administration

projects (US Million.)

Source: World Bank, Lending Database, 2006

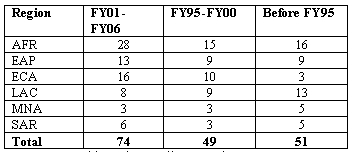

Table 2 illustrates that the number of these interventions amounted to 74

in FY01-06.

Table 2: Number of projects with land

administration component/s

Source: World Bank, Lending Database, 2006

Given the complexity and long-term nature of land-related institutions,

work on land would not be possible without having strong partnerships with a

wide range of development partners, civil society organizations and academic

institutions (Deininger, 2006). The Bank actively contributes to recent

initiatives such as the High Level Commission for Legal Empowerment of the

Poor, the Global Land Tools Network and is in regular contact with the

private sector through institutions such as the International Federation of

Surveyors (FIG) and with non-government organizations such through the

International Land Coalition. The Bank maintains close relationships with

United Nations organizations working in the land sector including Habitat,

the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) and United Nations Development

Program (UNDP).

5. LAND POLICY REFORM

Land policy is directly related to the broader concepts of land tenure

and property rights. Land, is perhaps, the “ultimate” resource. It is both a

physical commodity as well as an abstract concept related to the rights to

own or to use it. Land tenure may be seen as an institutional structure that

determines how individuals and groups secure access to the productive

capabilities of the land or other uses over the land. Land management is the

process through which land resources are utilized, while land administration

is more concerned with regulation which addresses issues related to land

information and how they can be utilized for effective and efficient land

management. These institutional structures are comprised of a mixture of

political, economic, legal, and social factors and relationships, each of

which has an impact on land rights and use (Marquardt, 2003).

Land policy reform serves a number of purposes, which may include: (i)

enhancement of security of tenure and providing the basis for determining

mechanisms for the distribution of land rights among citizens; (ii)

promotion of social stability by providing a clear statement of government

goals and objectives toward land; (iii) basis for economic development

because decision making is based on expectations and predictability; (iv)

ensuring sustainable land use and sound land management; and (v) guidance

for the development of legislation, regulations, and institutions to

implement the policy and monitor its impacts

Land policy to support land reform, is a complex, and long-term issue.

There is no absolute template for land policy and every country has its own

unique social, economic, political, environmental, historical, ethnic,

cultural, religious context and idiosyncrasies. What works in one country

may not be suitable and transportable to another country. In post-conflict

countries, tenure security and access to land are major factors in providing

long-term stability. All donors need to be cognizant of local conditions and

issues and work constructively and flexibly.

Deininger (2006) advises that the first and thus far only policy document

on land produced by the World Bank and formally approved by the Bank’s Board

is the 1975 “Land Reform Policy Paper” which by now is quite outdated in

many respects. To respond to demands for guidance by policy-makers and

staff, the Bank produced in 2003 a Policy Research Report (PRR) on ‘Land

Policies for Growth and Poverty Reduction’. This document was prepared in

close collaboration with the Bank’s regional departments and development

partners, and drew on a large body of research. Although the PRR is not a

formal Bank policy document, it has in practice assumed its place and become

a reference document for staff in the Bank and partner institutions. It is

based on four principles, namely: (i) the role of the state in establishing

secure property rights; (ii) the importance of well-functioning land markets

to provide land access; (iii) the social and economic costs of highly

unequal land distribution; (iv) the rationale for focusing regulation on

clear externalities and for having efficient government institutions dealing

with land. The PRR land policy principles are described below:

(i). Security of Property Rights: Land rights are social

conventions that regulate the distribution of the benefits that accrue from

specific uses of a certain piece of land. A number of arguments support

public provision of such rights. First, the high fixed cost of the

institutional infrastructure needed to establish and permanently maintain

land rights favors public provision, or at least regulation. Second, the

benefits of being able to exchange land rights will be realized only in

cases where such rights are standardized, regulated and can be easily and

independently verified. Finally, without central provision, households and

entrepreneurs will be forced to spend resources to defend their claims to

property, for example through guards, fences, etc. which is not only

socially wasteful but also disproportionately disadvantages the poor, who

will be the least able to afford such expenditures (Deininger, 2005).

Security of property rights and the ability to draw on local or national

authorities to ensure these rights, are key to increasing investment

incentives and productivity of land use. A wide range of options to increase

tenure security, from full formal title to legally backed mechanisms at the

community level, can result in higher levels of tenure security and studies

have shown large differences of land values for plots with more secure

tenure. Measures to improve tenure security can also improve the welfare of

the poor. However, in many cases, the land owners will need to pay

comparatively large amounts of “informal” payments to government officials

in order to secure their rights.

Security of tenure is critical in limiting land disputes, and promoting

social stability. Once land rights are obtained, how are those rights

protected? What assurance does the individual have that his/her rights to

land will be protected? Rights over land and property also carry an

obligation to respect the rights of others. Thus, there are social sanctions

over land rights as there are legal sanctions to protect land rights. Where

informal structures no longer function, formal, legal and administrative

structures need to be created to provide this assurance or security of

tenure. Of particular importance are the rights of vulnerable groups in

society such as women and orphans, as is highlighted in the Bank’s support

for property rights in Aceh following the tsunami. Aceh is also important as

it has only since late 2005, achieved peace, after some 30 years of

conflict.

Even though most countries mandate equality of men and women before the

law in principle, the procedures used by land administration institutions

often discriminate against women, explicitly or implicitly. To overcome

this, a pro-active stance in favor of awarding land rights to women by

governments, together with rigorous evaluation of innovative approaches

aiming to accomplish greater gender equality in control of conjugal land on

the ground may be warranted.

(ii). Well-functioning Land Markets: Improving tenure security

will provide direct benefits only to those who have access to land. Making

land rights transferable will not only further increase investment

incentives but also allow the landless to access land through markets.

Furthermore, transferability that is combined with formal title allows using

land as collateral for credit if credit markets are sufficiently developed.

Transferability is particularly important in dynamic environments to bring

about changes in land use and allow households to shift from agriculture to

non-agricultural occupations. Studies show that land rental improves

efficiency and equity in many settings. Land sales markets are often

“thinner” but in many circumstances can enable the poor to gain access to

land.

(iii). Equitable land distribution: Extreme inequality in the land

ownership distribution often goes hand in hand with under-utilization of

vast tracts of productive land and deep-rooted rural poverty. It is in the

state’s interest as well as the private individual’s interest to optimize

the productive use of the land. These uses include agriculture and pastures

as well as the provision of space for housing and commercial and industrial

enterprises. Government policy will help to determine how these production

and investment decisions are made by the state and by private individuals.

For a variety of reasons, markets alone are often unable to bring about the

changes required to attain an optimum structure of production. In this case,

ways to increase access to land by the poor have the potential of increasing

productivity. Also, as land is often intertwined with social exclusion and

acts as a social safety net, increased access to land can also promote

equality of opportunity. However, a large number of failed attempts at land

reform show that doing so effectively is not easy. Different instruments

that can range from land taxation, expropriation with compensation, to

activation of rental markets, may be appropriate. Cost and potential

benefits of such policies need to be carefully compared to that of other

alternatives that may not involve land.

How is access to land allocated among individuals and groups? Are there

mechanisms to ensure equal access or equal opportunities to access? The

former approach would be a more socialistic approach of guaranteeing access

to some land for everyone, but at the possible expense of economies of

scale. Over time, such a guarantee could lead to smaller and smaller parcels

of land as population grows and new people demand access to land. The latter

approach could be seen as a more capitalistic approach that would ensure

access to land for those who have the resources to use the land, but could

be at the expense of those with fewer or no resources. Over time, this could

lead to sizable landless populations that would be problematic if no

alternative forms of employment existed.

(iv). Regulation of Land: Although regulations are warranted where

there are clear externalities, failure to base zoning and regulation

concerning land use on assessment of the capacity needed to implement them,

the cost of doing so, and the way costs and benefits are distributed, has

often given rise to over-regulation which could subsequently degenerate into

a source of rent-seeking. Non-transparent, corrupt, or simply inefficient

land administration undermines the operation of the regulatory system and

public confidence.

Regulation is necessary to support environmental sustainability (Bell

2005). While the land resource of a country is finite and cannot be

expanded, the resource base can be improved upon and it can be degraded. It

is in the country’s interest to have its land resources used in a

sustainable manner to ensure that the land will remain productive into

future generations. Re-forestation and soil conservation programs have long

histories in most countries. However, there has been a great deal of recent

effort in the analysis of environmental impacts on land use practices.

Regulation is also necessary to protect the intrinsic historic and

cultural values of land (Bell 2005). A society’s identity is very much tied

to its history and the land it has settled and defended over time. Most

countries are comprised of ethnically and culturally diverse populations

which collectively create the social fabric of that nation. Policy decisions

can have significant impacts on society at large, ethnic minority groups and

small communities. The different value structures often have an impact of

land access and use.

Another intrinsic value of land is its aesthetic value. The landscape of

a country is a more ambiguous issue, but nonetheless an important

consideration in the development of land policy. Scenic vistas, clean,

free-flowing rivers, and well managed fields and forests give a positive

impression of the country, while denuded, eroded hillsides, urban slums and

polluted lakeshores present the opposite image. Again policy decisions can

have a positive or negative impact on these perceptions (Marquardt, 2003).

6. KEY OUTCOMES OF LAND REFORM PROJECTS

Improving tenure security. Given the fundamental role of secure

land tenure, programs to make land rights more secure have long formed a

major thrust of Bank interventions in this area, accounting for the largest

share of resources spent in the Bank’s land portfolio which currently has

loans amounting to more than $1 billion under supervision. As insecurity of

property rights is often rooted in ambiguous legal situations and complex or

non-transparent institutional arrangements, such programs have included not

only demarcation and issuance of certificates but also legal reform and

institutional restructuring.

Experience has provided a number of lessons:

- Insecure land tenure prevents large parts of the population from

realizing the economic and non-economic benefits such as greater investment

incentives, transferability of land, and improved credit market access, more

sustainable management of resources, and independence from discretionary

interference by bureaucrats, that are normally associated with secure

property rights to land. More than 50 percent of the peri-urban population

in Africa and more than 40 percent in Asia live under informal tenure and

therefore have highly insecure land rights. While no such figures are

available for rural areas, rural land users are reported to make

considerable investments in land as a way to increase tenure security

(Deininger, 2005).

- In many situations legal or institutional reforms will have more

far-reaching effects than issuance of certificates - and also be a

precondition for documentation to be sustainable, as in the Kyrgyz

Republic, Uganda, Cambodia, and Mexico. Such reform, which should take

particular precaution to establish transparent and accountable procedures

include recognition of secondary land rights, and prevent land grabbing by

powerful elites, will thus have to precede or be implemented at least

concurrently with efforts at issuing documents.

- Land administration should have comprehensive coverage, be affordable

given a country’s capacity and prevailing land values, and financially

self-sustaining.

- Pressures for uniformly high accuracy surveying and mapping are

generally unwarranted, especially for low-value rural lands. The focus

should be on the state providing a basic spatial framework, with the

option for higher accuracy surveys in areas where needed.

- Spatial information technology provides very useful tools to support

land administration and management. However, spatial information

technology is no substitute for good governance, transparent and

accountable service delivery, equity and justice. The most significant

challenges faced are still concerned with policy, law and institutional

reform. It is vital that the current ”spatial fad” not cloud the real

challenges that have to be addressed (Bell, 2004).

- Ensuring secure land tenure will be of particular relevance for

vulnerable groups who were traditionally discriminated against. Attention

to women’s rights will be warranted where women are the main cultivators,

where out-migration is high or control of productive activities is

differentiated by gender, or where adult mortality and unclear inheritance

regulations undermine women’s livelihood if their husband dies, as in

Africa with HIV/AIDS.

Strengthening Land Rental Markets. Deininger (2005) advises that

the Bank has long argued that, in order to realize the full benefits that

can accrue from rental markets, governments need to ensure that tenure

security is high enough to facilitate long-term contracts, and eliminate

unjustified restrictions on the operation of such markets. Limitations on

the operation of land sales markets may, in some cases, be justified on

theoretical grounds but extremely few situations where certain types of land

rental may need to be circumscribed. In practice, efforts to implement land

market restrictions have almost invariably weakened property rights and

their unintended negative consequences have far outweighed the positive

impacts they were intended to achieve. Therefore, there is a strong case for

eliminating restrictions on rental markets where they continue to exist.

Also, with few exceptions, e.g. (temporary) caps on speculative land

acquisition in the case of rapid structural change little can be said in

favor of sales market restrictions as a policy tool.

Land reform: Land reform has had varying degrees of success in

achieving greater efficiency and empowering the poor (Deininger, 2006).

While land reforms have achieved considerable success in some Asian

countries such as Japan, Korea and Taiwan, land reforms in Latin America

have often been less successful. One reason for limited impact was that

reforms were often guided by short-term political objectives, and that an

“agrarian” emphasis on full-time farming increased their cost (while

reducing the number of potential beneficiaries- and the reforms’ impact on

poverty. To ensure success, respect for existing property rights, access to

non-land assets, working capital, output and credit markets for

beneficiaries and a conducive policy environment are essential. Beneficiary

selection should be transparent and participatory, and attention needs to be

paid to the fiscal viability of land reform efforts. The Bank is exploring

ways to use market-based mechanisms to transfer land to poor beneficiaries

and to dealing with the legacy of aborted or only partially successful land

reforms, e.g. by eliminating overlapping property rights, in a number of

countries such as Brazil and South Africa.

Strengthening land administration capacity: Most Bank-funded

projects have given particular emphasis to capacity building in the

government institutions responsible for the public administration of land.

Often it is not just the lack of capacity in land administration which has

been the challenge, but also lack of capacity in public administration

generally. In addition, weak private sector capacity means that the

government must provide a greater range of services. Developing private

sector capacity in land administration and management should be viewed in a

broader context than just land surveying and may include other service

delivery areas including planning, ITC, valuation, law, conveyancing and

property sales.

The Bank realizes that one reason for the land administration system to

perform less than satisfactorily is unjustified government monopolies (e.g.

in surveying) that may promote ”rent seeking” and decrease the quality of

service provision. It does so in a project context and through participation

in international networks that promote use of modern technology to establish

low-cost and transparent land administration tools. It also supports gradual

devolution of responsibility for land use regulation and taxation to local

governments which, if coupled with capacity building, could make a

contribution to efforts towards more effective decentralization.

Dealing with Land Conflict: Increasing scarcity of land in the

presence of high rates of population growth, possibly along with a legacy of

discrimination and highly inequitable land access, implies that many

historical and contemporary conflicts have their roots in struggles over

land. This suggests a special role for land policy in many post-conflict

settings. An ability to deal with land claims by women and refugees, to use

land as part of a strategy to provide economic opportunities to demobilized

soldiers, and to resolve conflicts and overlapping claims to land in a

legitimate manner, will greatly increase the scope for post conflict

reconciliation and speedy recovery of the productive sector, a key for

subsequent economic growth. Failure to put in place the necessary mechanisms

may keep conflicts simmering, either openly or under the surface, with high

social and economic costs especially because, as time goes by subsequent

transactions will lead to a multiplication of the number of conflicts which

can result in generalized insecurity of land tenure (Deininger, 2005).

8. GOOD GOVERNANCE

Throughout the world, land-related development cooperation is giving

sufficient attention to integrating governance principles and safeguards

into the design, implementation and impact monitoring of land administration

and management projects. Although secure tenure and access to land have been

universally accepted as the base for economic and social development, recent

privatization of land, liberalization of land markets, and increasing demand

and competition for land, have in many developing countries led to

insecurity, betterment of the rich, and deprivation of the poor. A primary

cause of this is weak governance in land administration. Deininger (2005)

notes that if institutions are weak, this can be a ”hot-spot of red tape and

corruption”, as in the case of India where a recent study estimated annual

bribes paid in the land sector at a staggering US $700 million.

While technical solutions for supporting land administration are

generally accessible, affordable and appropriate, the problems caused by

corruption, the general lack of law and order, and poor public sector

management have become recognized as the key barriers to land administration

reform, development of formal land markets, public confidence and

investment. Good governance in land administration aims to protect property

rights of individuals as well as of the state by introducing principles such

as transparency, accountability, rule of law, equity, participation and

effectiveness into land related public sector management.

The public administration of land, including the management of state

lands, has a high potential for abuse. In many countries, corruption and

abuse of power have resulted in the undermining of tenure security. As a

consequence this has adversely impacted the business climate and economic

activities due to increased costs of doing business, lack of confidence of

the private sector, and under-utilization of land. At the same time, high

costs and inefficient prolonged procedures due to corrupted land

registration systems discourage people to register their land, and operate

within the informal land market sectors. This also impacts land tax revenue,

and reduces government spending on the provision of public services and

infrastructure.

9. CASE STUDY: RESPONDING TO DISASTERS AND CONFLICT IN ACEH

Responding to the land issues in Aceh (Indonesia) has been especially

challenging given the disasterous tsunami and earthquakes, as well as the

long-running civil war.

On December 26, 2004, a 9.0 magnitude earthquake struck 150 kilometers

off the coast of Aceh, on the island of Sumatra in Indonesia. Forty-five

minutes later, a tsunami wave hit Aceh, and with minutes it swept clean an

800 kilometer coastal strip of Aceh. This is equivalent to the coastline

from San Francisco to San Diego. A reported 130,000 people were killed and

37,000 remain missing. The actual toll could be as high as 170,000. Up to

500,000 people were made homeless. On March 28, 2006, a major earthquake

added to the toll in Nias (an island off North Sumatra), Simuleu (island off

Aceh) and southern parts of Aceh. The December 2005 earthquake caused the

2,000 sq. km. Island of Simuleu with its 78,000 inhabitants, to sink about

one meter, while the March 2006 earthquake caused it to rise two meters, or

even more in some locations. In addition to the huge loss of human life,

these events caused immense social, economic and environmental devastation

to areas that were already impoverished and reeling from almost 30 years of

armed conflict.

The tsunami appeared to bring an ”informal” truce to the 30-year

conflict. However, incidents continued. For example, during the first month

following the tsunami, the Indonesia government reported (January 24, 2006)

that 200 insurgents had been killed. On August 15, 2005, the Government of

Indonesia and the Free Aceh Movement (GAM) signed a peace accord in

Helsinki, intended to end the three decades of armed conflict, which had

resulted in 15,000 deaths of civilians, separatist insurgents and soldiers.

The peace agreement, which continues to hold, has been described as the

silver lining in the dark clouds of the tsunami and earthquake disasters

(BRR, 2005). The de-mobilization of former GAM soldiers has created a number

of land-related challenges, including the provision of land for farming to

provide livelihoods for former GAM soldiers and also the controlling of

illegal logging by unemployed former GAM soldiers.

The reconstruction of Aceh and Nias is estimated to require at least

US$5.8 billion to restore lost assets. This includes taking into account

rising inflation due to high demand for reconstruction related goods. One

year after the tsunami, US$4.4 billion, from the international community,

had already been allocated for specific reconstruction projects. The Bureau

of Reconstruction and Rehabilitation (or Badan Rehabilitasi dan Rekonstruksi

–BRR) has adopted the theme of “build back better”. Progress is being made,

though it will take many years to achieve sustainability. The reconstruction

of Aceh sees the majority of MDG being directly addressed. The Multi-Donor

Fund (2006), which is jointly chaired by the World Bank, BRR and Ambassador

of the European Commission, reports on funding a portfolio of 16 projects,

mobilizing US$392 million to support: (i) recovery of communities; (ii)

infrastructure and transport; (iii) sustainable management of the

environment; and (iv) capacity building and governance.

The tsunami and earthquakes caused significant damage or destruction to

property on extensive tracts of land. While some of the land can be

rehabilitated, in many areas the land became permanently submerged or was

washed away into the sea. Many land parcels will never be habitable or

productive again, requiring relocation of surviving owners and families.

Much farm land was washed away or damaged by salt water. Even where

communities can re-build on original locations, many households need to move

to facilitate improved community spatial plans that provide wider roads,

facilities and escape routes. Significant losses were sustained by the land

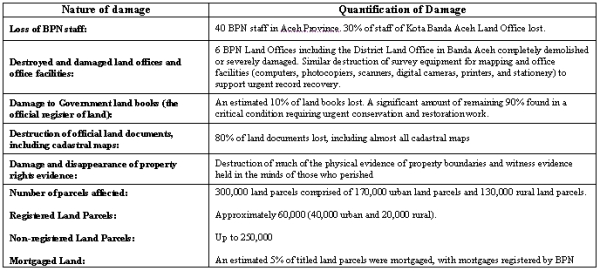

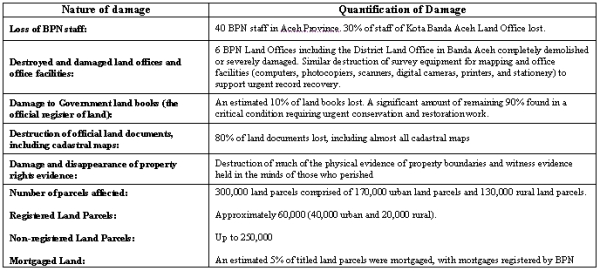

administration system, as summarized in Table 3.

Table 3: Damage to property Rights and the Land

Administration System in Aceh and Nias

The implementation framework for the reconstruction of property rights

adopted by the government is provided under the Reconstruction of Aceh Land

Administration (RALAS) Project, being implemented under the direction of the

National Land Agency (Badan Pertanahan Nasional – BPN), and funded by a

three-year, $28.5 million multi-donor grant through the World Bank. The

broad goal of the project is to improve land tenure security in Aceh with

specific objectives to: (i) recover and protect ownership land rights of the

people in the affected and surrounding areas; and (ii) rebuild the land

administration system

RALAS aims to ensure that community-led processes are conducted to a

standard that will have a strong-legal basis for future titling by

landowners. Key land challenges facing the reconstruction of Aceh include:

(i) complex Indonesian laws and Syariah law; (ii) land speculation; (iii)

evictions from land; (iv) protection of the rights of widows and orphans;

(v) land requirements for demobilized GAM soldiers; (vi) relocation of

communities whose land was submerged or became uninhabitable; (vii) land

consolidation, re-allocation and spatial planning; and (viii) good

governance.

The protection of land and property rights is seen as fundamental for

long-term reconstruction efforts and peace, as well as advancing the social,

economic and cultural rights of the people (BRR, 2005). Implementation of

RALAS, and its linkages with the broader reconstruction program,

demonstrates the particular unique, complexities experienced by land

administration and management in addressing the MDG.

10. CONCLUSION

Land administration and management reforms are complex and long-term.

Measures to increase land tenure security, reduce the transaction costs of

transferring land rights, establish an appropriate regulatory framework and

prevent undesirable externalities, usually cut traditional institutional

boundaries. It is essential to have a long-term vision and to include land

policy issues in the overall framework of a broadly based development

strategy that addresses the wider social, economic and environmental agenda.

The extent to which objectives are achieved should be independently

monitored, and jointly with other government programs aimed at poverty

reduction and economic development. Land policy has a special role for many

post-conflict settings in providing a stable foundation and maintaining the

peace. Land reform has an integral role in meeting the challenges of the

MDG.

REFERENCES

- Badan Rehabilitasi dan Rekonstruksi (BRR), 2005, “Aceh and Nias One

Year Alter the Tsunami: The Recovery Effort and Way Forward”, Joint Report

of the BRR and International Development Partners, December 2005.

- Benny, 2005, “Reconstruction of Land Administration System in Aceh and

Nias”, FIG EGM, Bangkok Dec 8-9, 2005.

- Bell, K.C., 2004, “Developing Asia and the Pacific: World Bank

Financed Land Projects”, Third Regional FIG Conference for Asia and the

Pacific, Jakarta, October 3-7, 2003.

- Bell, K.C., 2005, ”Land Administration and Management: The Need for

Innovative Approaches to Land Policy and Tenure Security”, FIG EGM,

Bangkok Dec 8-9, 2005.

- Clinton, W, 2005, “Report to the UN Economic and Social Council, by

the UN Special Envoy for Tsunami Recovery”, New York City, July 14, 2005.

- Deininger, K., 2005, ”Land Policies for Growth and Poverty Reduction:

Key Issues and Challenges Ahead”, FIG, Mexico.

- Deininger, K., 2005, ”Land Policy and Operations at the Bank:

Principles and Operational Implications”, World Bank (unpublished).

- Enemark, S., 2006, ”Responding to the Millennium Development Goals”,

FIG XXIII Congress, Munich, October 2006.

- International Federation of Surveyors, 1998, ”Cadastre 2014: A Vision

for a Future Cadastral System”, FIG, July 1998.

- Marquardt, M., 2003, ”Land Policy Issues Paper”, University of

Wisconsin.

- Multi Donor Fund for Aceh and Nias (MDF), 2006, The First Year of the

Multi Donor Fund Results, Challenges and Opportunities, Progress Report

II, June 2006.

- United Nations, 2000, “United Nations Millennium Declaration”,

Millennium Summit, New York, Sep. 6-8, 2000. UN, New York.

- United Nations, 2001, “Road Map Towards the Implementation of the

United Nations Millennium Declaration”, Report of the Secretary General.

UN, New York.

- United Nations, 2005, “The Millennium Development Goals Report”, UN,

New York.

- World Bank, 1975, “Land Policy Reform Paper” World Bank, Washington

D.C.

- World Bank, 2002, “The MDGs as a Benchmark for Development

Effectiveness”, World Bank, Washington D.C.

- World Bank, 2002, “Achieving Development Outcomes: The Millennium

Challenge”, World Bank, Washington D.C.

- World Bank, 2003, “Land Policies for Growth and Poverty Reduction”,

Policy Research Report (PRR), World Bank, Washington D.C.

- World Bank, 2003, ”Comparative Study of Land Administrative Systems

Global Synthesis of Critical Issues and Future Challenges”. (unpublished).

- World Bank, 2005, ”Conflict and Recovery in Aceh – An Assessment of

Conflict Dynamics and Options for Supporting the Peace Process”.

- World Bank, 2006, “Global Monitoring Report, 2006”, World Bank,

Washington D.C.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The author is indebted to the guidance and inputs by Klaus Deininger and

the World Bank’s Land Thematic Group, in the preparation of this paper.

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Keith C. Bell joined the World Bank in 2003, after a distinguished

career in both the public sector and the Army in Australia, culminating as

the Surveyor-General of Victoria, 1999-2003. Prior to this he held a range

of senior positions including: General Manager in Planning and Land

Management of the Australian Capital Territory Government 1997-1999;

Executive Officer (and Secretary) of the Australian New Zealand Land

Information Council (ANZLIC); and Director of the National Land Data Center

in the Australian Government. His early career saw him work in the

exploration industry, hydrography and private sector land development.

Within the World Bank, he has responsibility for supporting land

administration projects throughout the East Asia Region, and works in

Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao Peoples Democratic Republic, Philippines and

Vietnam. In early 2005, he commenced leading efforts to deal with land and

property rights in Aceh and North Sumatra following the tsunami disaster. He

has only recently returned to Bank headquarters. He is a licensed surveyor

and engineer, and has higher degrees in science, human resource management

and business administration. He is a Fellow of several professional

institutions including: (i) the Institution of Engineers, Australia; (ii)

the Institution of Surveyors, Australia; (iii) Australian Institute of

Company Directors; and (iv) the Australian Institute of Management. He is

also a Member of the American Society of Civil Engineers. In 2003, he was

awarded a Doctor of Applied Science (Honoris Causa) from the Royal Melbourne

Institute of Technology (RMIT) University. He has also received a number of

military decorations and awards.

CONTACTS

Keith C. Bell

The World Bank, East Asia Pacific Region

1818 H Street, NW

Washington D.C., USA

Tel. + 1 202 458 1889

Fax + 1 202 477 2733

Email: kbell@worldbank.org

Web site: www.worldbank.org

|