ABSTRACT

Only 1.5 billion of the estimated 6 billion land parcels world-wide

have land rights formally registered in land administration systems.

Many of the 1.1 billion slum dwellers and further billions living under

social tenure systems wake up every morning to the threat of eviction.

These people are the poor and most vulnerable and have reduced forms of

security of tenure; they are trapped in poverty. Increasing global

population and the rush to urbanisation is only going to turn this gap

into a chasm.

This paper explores one potential solution to the security of tenure gap

through establishing a partnership between land professionals and

citizens that would encourage and support citizens to directly capture

and maintain information about their land rights. The paper presents a

vision of how this might be implemented and investigates how the risks

associated with this collaborative approach could be managed.

1. INTRODUCTION

Land Administration Systems (LAS) provide the formal governance

structures within a nation that define and protect rights in land,

including non-formal or customary institutions. Their benefits range

from guarantee of ownership and security of tenure through support for

environmental monitoring to improved urban planning, infrastructure

development and property tax collection. Successful land markets depend

on them.

Despite this pivotal support of economic development, effective and

comprehensive LAS exist in only 50 mostly western countries and only 25

percent of the world’s estimated 6 billion land parcels are formally

registered in LAS. This leaves a large section of the world’s population

with reduced levels of security of tenure, trapping many in poverty.

Missing and dysfunctional LAS can precipitate problems such as conflicts

over ownership, land grabs, environmental degradation, reduced food

security and social unrest. Rapid global urbanisation is exacerbating

these discrepancies.

This security of tenure gap cannot be quickly filled using the current

model for registering properties that is dominated by land

professionals. There are simply not enough land professionals

world-wide, even with access to new technologies. To quickly reduce this

inequality we need new, innovative and scalable approaches to solve this

fundamental problem. This is one of our fundamental global challenges.

This paper explores one potential solution to the security of tenure

gap: ‘crowdsourcing’. Crowdsourcing uses the Internet and on-line tools

to get work done by obtaining input and stimulating action from citizen

volunteers (www.crowdsourcing.org). It is currently used to support

scientific evidence gathering and record events in disaster management,

as witnessed in the recent Haiti and Libya crises, for example. These

applications are emerging because society is increasingly spatially

enabled. Establishing such a partnership between land professionals and

citizens would encourage and support citizens to involve themselves in

directly capturing and maintaining information about their land rights.

Although citizens could use many devices to capture their land rights

information, this paper advocates the use of mobile phone technology.

Due to high ownership levels (5 billion licenses world-wide) and

widespread geographic coverage (90 percent of the world’s population can

obtain a signal), especially in developing countries, mobile phones are

an excellent channel for obtaining crowdsourced land administration

information. Frugal innovation is making them affordable for all,

especially in developing countries where a new generation of information

services in health and agriculture, for example, is turning the mobile

phone into a global development tool.

Mobile phones are progressively integrating satellite positioning,

digital cameras and video capabilities. They provide citizens with the

opportunity to directly participate in the full range of land

administration processes from videoing property boundaries to secure

payment of land administration fees using ‘mobile’ banking. But even

today’s simpler phones offer opportunities to participate in

crowdsourcing.

A key challenge in this innovative approach is how to ensure

authenticity of the crowdsourced land rights information. The paper

explores applicability of the approaches adopted by wikis (a piece of

server software that allows users to freely create and edit Web page

content using any Web browser), e-commerce and other mobile information

services and recommends the initial use of trusted intermediaries within

communities, who have been trained and have worked with local land

professionals. This approach has the potential to provide a good level

of authenticity and trust in the crowdsourced information and would

allow a significant network of ‘experts’ to be built across communities.

To optimise the scarce resources, these intermediaries could be involved

in a range of other information services, such as health, water

management and agriculture.

2. ARE CURRENT LAND ADMINISTRATION SYSTEMS DELIVERING THE EXPECTED

BENEFITS?

Despite the clear link between effective LAS and efficient land

markets (Al- Omari, 2011), sustainable development and the other

benefits, their current adoption and effective implementation are

limited to about 50 and found mainly in western countries and in

countries in transition in central Asia (Enemark et al, 2010). A number

of factors limit their scope of implementation:

- Costs are significant and national solutions can take from five

to over 20 years to implement.

- Overly complex procedures lead to high service delivery costs

and end user charges, excluding the poor and the vulnerable.

- Lack of a supporting land policy framework ensures that the LAS

do not deliver against the main drivers of land tenure, land markets

and socially desirable land use.

- Insufficient support for social and customary tenure systems

excludes large proportions of the population.

- Lack of transparency encourages corruption in the land sector,

lowering participation through lack of trust.

- Communication channels to customers are either office or

Internet based and lead to geographic discrimination or exclusion

through the ‘digital divide’.

- A mortgage requires a bank account and credit rating, which is

difficult for the poor and those remote from financial services to

obtain.

- Cadastral surveys using professional surveyors are normally

mandatory and generate higher fee rates, e.g. in the USA a typical

residential land parcel costs $300 -$1,000

(http://www.costhelper.com/cost/home-garden/land-surveyor.html) to

survey depending on local rates and the size and type of parcel.

It is estimated that there are around 6 billion land parcels or

ownership units world-wide. 4.5 billion parcels are not formally

registered and of these 1.1 billion people live in the squalor of slums.

With urbanisation predicted to increase from the current 50% to 60% in

2030 and a further 1 billion being added to the world’s population in

this timeframe, the security of tenure gap will become a chasm. This

will be impossible to fill in the foreseeable future using the currently

available land administration capacity. The International Federation of

Surveyors (FIG) currently represents 350,000 land professionals

world-wide. The current LAS paradigm cannot be scaled up quickly enough

to meet the demand.

The lack of effective, affordable and scalable LAS solutions conspires

to limit access to land administration services by large sections of

society, especially the most vulnerable, leaving them trapped in

poverty. There is a pressing need to radically rethink LAS: simplify

procedures, reduce the cost of transactions, and open new channels for

participation. Crowdsourcing through ubiquitous mobile phones, for

example, offers the opportunity for land professionals to form a

partnership with citizens to create a far-reaching new collaborative

model and generate a set of LAS services that will reach the world’s

poor. The rest of this paper explores how citizens can be empowered to

support the delivery of LAS services through crowdsourcing.

3. A NEW CITIZEN COLLABORATION MODEL FOR LAND ADMINISTRATION

This section provided a vision of how citizens armed with mobile

phones, with the help of land professionals, could effectively capture

and manage their land rights.

3.1 The Increasingly Pervasive Mobile Phone

Although citizens can provide their crowdsourced data through a

number of traditional channels, including paper, mobile phones are

progressively proving to be the device of choice. Mobile phones have

made a bigger difference to the lives of more people, more quickly, than

any previous communications technology. They have spread the fastest and

proved the easiest and cheapest to adopt. In the 10 years before 2009,

mobile phone penetration rose from 12 percent of the global population

to nearly 76 percent. It is estimated that around 5 billion people

currently have mobile phones and 6 billion will have them in 2013

(http://www.itu.int/ITU-D/ict/statistics/)

Recently the fastest growth has been in developing countries, which had

73 percent of the world’s mobile phones in 2010, according to estimates

from the International Telecommunications Union

(http://www.itu.int/ITU-D/ict/statistics/). In 1998, there were fewer

than four million mobiles on the African continent. Today, there are

more than 500 million. In Uganda alone, 10 million people, or about 30

percent of the population, own a mobile phone, and that number is

growing rapidly every year. For Ugandans, these ubiquitous devices are

more than just a handy way of communicating: they are a way of life

(Fox, 2011). Not all phones in the developing world are in individual

use, but are actually used as a communal asset of the household or

village.

Due to their high ownership levels and widespread geographic coverage,

especially in developing countries, mobile phones are therefore an

excellent channel for obtaining crowdsourced land administration

information. But are they affordable and do they have the necessary

functionality?

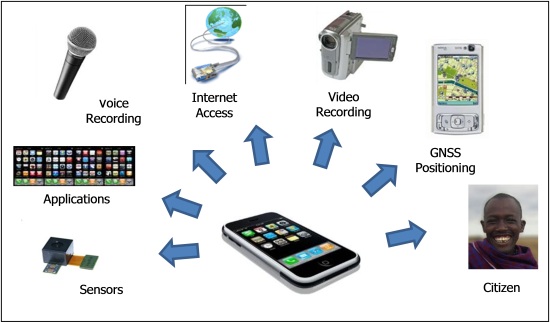

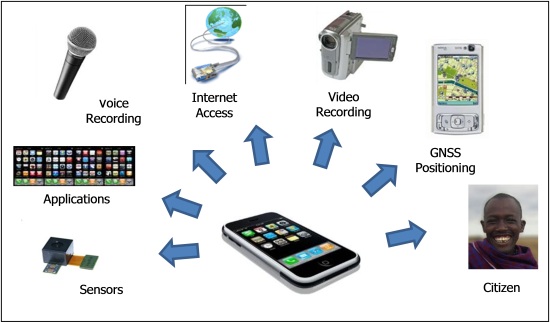

3.2 The rise of smart phones and tablets

Telecommunications has developed exponentially. Phones have changed:

there is a big shift from holding a phone to your ear to holding it in

your hand. Smart phones have emerged that are able to browse the web,

send and receive email, and run applications - as well as storing

contacts and calendars, sending text messages and (occasionally) making

phone calls. See figure 1 for the range of Cyborg (an organism that has

enhanced capabilities due to technology) functionality provided by smart

phones. Smart phones represented 24 percent of all mobiles sold

worldwide in the first quarter 2011 – up from 15 percent a year before.

The tipping point when they make up 50% may only be a year or so away.

Although smart phones may cost around US$600 today, volume of sales and

frugal innovation will drive the cost down to an estimated US$75 in

2015. A US$100 smartphone has already arrived on the streets of Nairobi.

Before the end of the decade, every phone sold will be what we'd now

call a smartphone and cost US$25 (Arthur, 2011).

Although smart phones have combined an array of technologies onto the

mobile phone platform to significantly increase its functionality and

its applicability in a wide range of new applications, regular mobile

phones can still be used to support information services and gather

crowdsourced information, through text messaging services (SMS) for

example.

The emergence of tablets is also providing an opportunity for

effectively supporting crowdsourced information, especially graphical

information. This technology will play a significant role in the future

of crowdsourcing.

Figure 1: Smart Mobile Phone

Cyborg Functionality

3.3 Vision of an effective crowdsourced Land Administration

solution

This increase in functionality of the mobile phone, its migration to

lower cost devices through frugal innovation, its increasing

pervasiveness across developing countries and its connection to Internet

and information services is opening up significant opportunities for its

use in delivering more effective and accessible land administration

services. The possibilities are explored below:

Accessing Customer Information Services - A whole new generation of

innovative information services, such as agricultural and health, are

being provided to users of mobile phones in developing countries. A good

example is the use of mobile phones to record and transfer water quality

or water source inspection data from the field to a central database

where water sector professionals can then view the data collected and

identify hazardous water sources

(www.bristol.ac.uk/aquatest/about-project/workplan/ma6/). A similar set

of land administration services for users could provide explanations of

procedures, electronic forms for completion, standard applications and

best practice for land registration and cadastre, for example. This

remote guidance and support will be essential when there is more

significant citizen participation in land administration services and

could be provided by tiers of citizen intermediaries with guidance by

Land Professionals.

Recording Land Rights - The mobile phone will allow citizens to directly

record the boundaries of their land rights. This can be achieved in

several ways:

- Marked up paper maps digitally photographed with the phone.

- A textual description of the boundaries recorded on the phone.

- A verbal description recorded on the phone.

- Geotagged digital photographs of the land parcel recorded on the

phone.

- A video and commentary recorded on the phone – this could

include contributions from neighbours as a form of verification

(mobile phone numbers of neighbours could be provided).

- The positions of the boundary points identified and recorded on

imagery using products such as Google Maps and Bing, for example.

- The co-ordinates of the boundary points recorded directly using

the GNSS capability of the phone.

In all cases the authenticity of the captured information would be

enhance by passively recording the network timestamp at time of capture.

This information is not something that most (99.999%) of users can

tamper with.

The results of this crowdsourced or self-service information could then

be submitted electronically to either the land registration and

cadastral authority or open data initiative for registration. Although

there are limitations in the quality and authenticity of the ownership

rights information provided, it could form the starting point in the

continuum of rights (UN-HABITAT, 2008) being proposed by UN-HABITAT.

This recognises that rights to land and resources can have many

different forms and levels.

To increase the authenticity and quality of the registration

application, the concept of the ‘Community Knowledge Worker’ created by

the Grameen Foundation (Donovan, 2011) could be adopted. The ‘Community

Knowledge Workers’ are trained members of communities supporting

agricultural and health information services who act as trusted

information intermediaries to those who have limited skills and access

to information. A similar model could be used for crowdsourced land

administration services to record or check ownership rights prior to

their submission. In fact, the ‘Community Knowledge Workers’ model could

be extended to also support land administration information services.

This model is similar to the administrative roles of the Patwari in

India and the Lurah in Indonesia.

This engagement of local communities is also being highlighted as a key

success factor by crisis mapping projects. They realise that without

community buy-in, the valuable crisis mapping tools will not be used.

Communities must be engaged at all stages of the project and technical

design to ensure that crisis mapping efforts are in line with local

incentives and capacities. For example, this community led approach

brought fourteen organisations into a network in Liberia contributing

data to a multi-layered map that served as a central nervous system for

early warning signs of conflict in the run up to the national elections

in 2011 (Heinzelman et al, 2010).

When the captured land rights are submitted to the property register

(see section 4 for a discussion on an alternative shadow property

register based on an open data initiative) a variety of quality checks

could be applied to the submitted information, including: random checks

in the field; comparisons with other applications submitted in the same

proximity; checks on ownership of the mobile phone; review evidence for

the location of its owner through the log showing that the phone is

frequently used within a location; network time stamping of captured

information; and contact the client and their neighbours on their mobile

phones to ask for clarification. Further details of approaches to

managing the authenticity risk are contained in section 5 ‘Managing the

Risks’.

Obtaining Title - The submission of an application for registration

usually involves the payment of a fee. This is normally paid as cash

over the counter or a financial transaction through a bank or post

office. However, in the context of mobile phones, the payment could be

made by the client through ‘mobile banking’ on the mobile phone.

Mobile phones are currently being used to manage identification

information. In Finland chip ID cards for government employees are being

adopted throughout Finnish central government. It is therefore feasible

that encrypted forms of land title could be incorporated into clients’

mobile phones and used as proof of ownership.

Accessing Land Information - Effective LAS are supported by Land

Information Systems. These are initially developed to support the

internal operations of the land registration and cadastral authority.

However, the next development stage is to make them outward facing and

accessible by customers either by Extranet or Internet. However, with

mobile phones directly supporting Internet access, these information

services can now be accessed by mobile phones. This new channel, which

will be the only access to the Internet for many countries, creates much

more accessibility for the citizen, bringing land administration

services to a wider range of society, many of whom are currently

excluded.

Paying Mortgage Instalments - Securing a mortgage normally requires the

property owner to have a bank account to support the mortgage payments

transactions. However, the mobile phone offers opportunities to provide

secure payment of land administration fees with the increasing use of

‘Mobile Banking,’ simplifying the procedures and again potentially

opening up the means of wider property ownership.

4. IMPACT OF NEW CITIZEN COLLABORATION MODEL ON THE EXISTING LAND

ADMINISTRATION SECTOR

The introduction of this new LAS model will likely be perceived by

most land professionals working in the land administration sector as

radical and by some as a serious threat. However, the current generation

of mobile phones and other devices are increasing the potential range of

participants in land administration. We are seeing the rise of the

‘proamateur’, somewhere between the professional and the amateur, caused

by this easy to use and accessible technology. Disruptive technology has

caused professional realignments in the past: total stations allowed

surveying technicians to perform more tasks, more accurately than

before. Crowdsourcing by ‘proamateurs’ is not a risk to land

professionals, but allows a wider range of participants to be involved

in land administration and more quickly address and solve our global

challenges.

Land professionals’ attitudes towards this new model will determine how

land administration is shaped in the future. Here are two scenarios of

the potential impact of the new model on the land administration sector.

Rejection by Land Professionals: Shadow Property Register - In countries

where there is little citizen trust in poorly performing or corrupt land

administration services provided by the government, an alternative

property register may be created through crowdsourcing. This ‘shadow’

property register would be similar to the OpenStreetMap crowdsourced

model that has successfully provided an alternative source of mapping

for many countries. An ‘OpenCadastralMap’ (Laarakkar and de Vries, 2010)

or ‘OpenLandOwnership’ open data initiative would emerge. Despite not

having the usual endorsement and guarantee from government, its

legitimacy may progress over time as quality and trust evolve. It may

even be embraced by the informal market as a trusted repository to

support transactions more affordably and effectively than the formal

property register. The real test will be if financial services use it to

judge risk in the mortgage market. Ultimately, it may either replace the

government land administration service, reinforcing the informal land

market, or be adopted by government once it has reached a critical mass

and quality.

Acceptance by Land Professionals: Supplement to the Formal Property

Register - Other countries may embrace this new model as an opportunity

to accelerate the number of properties being registered across the

country and support a much more inclusive solution to land

administration. If land professionals work in partnership with citizens

and communities and grow a network of trusted citizens to record and

register land rights then this source of land information could be

managed directly by the formal property registers. Initially these

crowdsourced records could have a provisional status that would be

formalised following checks on authenticity. This could be performed

directly by land administration staff or accepted directly from trusted

community experts or quality checks achieved through crowdsourcing. The

approach to and judgement of authenticity would evolve and improve over

time, just as has happened with the maintenance of all wikis. This would

involve a changing role for land professionals, working with citizens

rather than for citizens.

In emerging nations where there are insufficient land surveyors or land

surveyors do not wish to embrace a crowdsourced approach, the lawyers,

assessors or even bankers may eventually try to remove or at least

reduce the need for land surveyors in the property transaction by either

resorting to direct crowdsourcing or identifying another type of

intermediary to facilitate crowdsourcing in different communities in

exchange for some cash or in-kind consideration.

5. MANAGING THE RISKS

As with all radical changes to long standing approaches, vested

interests will be jeopardised and entrenched opposition will inevitably

be encountered. Here are some of the risks that will most likely be

raised to attempt to keep the status quo.

5.1 Can crowdsourced land rights information be sufficiently

authenticated?

One of the most contentious issues surrounding crowdsourced

information is the authenticity or validity of the information provided.

Without the rigors and safeguards associated with formal professional

and legal based processes, crowdsourced information is of variable

quality and open to potential abuse. Crowdsourced information has

provided input to wikis, feedback of quality of services and counting

birds, for example, but is not normally used to capture information as

critical and legally binding as property rights in an authoritative

register. So what techniques could be used to quality assure the

authenticity of the information to a level that would be acceptable for

inclusion in a property register? Some alternatives, including lessons

learned from leading wikis and e-commerce, are discussed below. However,

the most appropriate crowdsourcing approaches to authenticity assessment

will only be identified through testing in the field.

Grameen Community Knowledge Workers as Intermediaries

This approach would avoid open, direct crowdsourcing at the outset and

only allow information to be provided by trusted intermediaries within

communities who have been trained and have worked with local land

professionals. Initially, there would be comprehensive quality assurance

of the crowdsourced information, but over time as trust is established

with the intermediaries the level of quality assurance sampling could

significantly decrease. These initial intermediaries could then train

further experts to build a significant network of ‘experts’ across

communities. Each expert would be continually checked and appraised to

determine the level of expertise and trust in the associated

crowdsourced information. To optimise the scarce resources, the

intermediaries could be shared with a range of information services,

such as health and agriculture.

Community based Quality Assurance

Quality assurance could be directly provided by members of the local

communities who take direct responsibility for authenticity. The

crowdsourced land right claims could be posted for communities to review

and comment on. Some form of local or regional land tribunal could be

established to arbitrate on conflicting claims. Once a critical mass of

land rights information is obtained it is then easier to identify

anomalies and conflicting claims. Levels of trust and accuracy of the

land rights would be upgraded over time as more evidence and cross

checking validates the claims.

Wiki and e-Commerce Solutions

Beyond local involvement in quality assurance, a centralised user

reputation system based on feedback from crowdsourced registrations,

similar to the buyers’ ratings of the sellers used in eBay, could be

used to assess the credibility of contributors and the reliability of

their contributions (Coleman, 2010). Leading wikis, such as

Wikipedia.org, originally relied solely upon the "wisdom of the crowds"

to evaluate, assess and, if necessary, improve upon entries from

individual contributors, usually with great success. However, recent

contributions of deliberate misinformation to specific entries have

caused Wikipedia to re-assess its approach. Beginning in December 2009,

it has relied on teams of editors to adjudicate certain "flagged

entries" before deciding whether or not to incorporate a volunteered

revision (Beaumont, 2009).

Although the data that are contributed to VGI projects do not comply

with standard spatial data quality assurance procedures and the

contributors operate without central co-ordination and strict data

collection frameworks, research of VGI is starting to provide methods

and techniques to validate quality and also the needed evidence to show

that this data can be of high quality. Recent research (Haklay et al,

2010) supports the assumption that as the number of contributors

increases so does the quality; this is known as ‘Linus’ Law’ within the

Open Source community. Studies were carried out using the OpenStreetMap

dataset showing that this rule indeed applies in the case of positional

accuracy.

Crowdsourcing Quality Assurance

Some elements of the quality assurance process do not require local

knowledge of the land rights claim and could be crowdsourced to a

network of informed consumers and world-wide professionals or could even

be automated.

Passive Crowdsourcing Quality Assurance

Mobile phones can also be used passively to collect evidence that

supports validation of user entered information. For example, the use of

a mobile phone is continually logged and this log can be analysed to

show where the phone is frequently used, inferring the location of the

owner. The network timestamp is another robust piece of evidence that

could be associated with collected land rights data, such as images or

videos. This is not something that most (99.999%) of users can tamper

with.

The extent to which control is held by the contributor, by the

institution, or by "the crowd" of contributors assessing each other's

contributions may be different across different implementations of

crowdsourcing.

5.2 Will openness lead to more corruption in

the land sector?

Land administration is often perceived as one of the most corrupt

sectors in government. Although individual amounts may be small, petty

corruption on a wide scale can add up to large sums. In India the total

amount of bribes paid annually by users of land administration services

is estimated at US$ 700 million (Transparency International India,

2005), equivalent to three-quarters of India’s total public spending on

science, technology, and the environment. However, one of the best means

of reducing corruption within a good governance framework is through

transparency of information and the ability to have two-way interaction

with clients.

Data collected by the public must be validated in some way, otherwise

the crowdsourced information is open to abuse, and in the case of land

rights, corruption through false claims. However, transparency, which is

at the heart of the crowdsourced philosophy and the increasing use of

the mobile phone to check authentication, should support a fight against

corruption.

5.3 Will Land Professionals form a new

partnership with citizens?

This new partnership model implies that Land Professionals will have

a different relationship with citizens or ‘proamateurs’. The increased

collaboration with citizens opens up the opportunity for new services to

train citizens and community intermediaries and to quality assure their

crowdsourced information. It should therefore not be perceived as a

threat to their livelihoods and profession. But will Land Professionals

accept this new role and will sufficient citizen entrepreneurs provide

land rights capture services and become trusted intermediaries?

Disruptive technologies have and will continue to challenge the

relationship between ‘proamateurs’ and land professionals, but these

drivers of change also present significant opportunities for all

stakeholders.

5.4 Will crowdsourcing just reinforce the informal land market?

There is a danger that the emergence and acceptance of crowdsourced

land rights information by citizens will just reinforce the informal

land markets in countries where there is ineffective land governance,

poorly performing land administration systems and weak formal land

markets. Lack of trust in the formal land administration system will

persuade citizens to try crowdsourcing alternatives that are attractive

due to their transparency and citizen involvement. The final outcome of

the informal or formal market will depend on the Land Administration

agencies’ reaction to crowdsourcing and whether they reject or embrace

it.

5.5 Who will provide the ICT infrastructure to support this

initiative?

The implementation of crowdsourcing in land administration requires

technical infrastructure to support the uploading, management and

maintenance of the land rights information. The implementation could

mirror the voluntary support model of OpenStreetMap. OpenStreetMap's

hosting, for example, is supported by University College London’s VR

Centre for the Built Environment, Imperial College London and Bytemark

Hosting, and a wide range of supporters

(http://wiki.openstreetmap.org/wiki/Partners) provide finance, open

source tools or time to support the initiative.

6. CONCLUSIONS

Crowdsourcing within the emerging spatially enabled society is

opening up opportunities to fundamentally rethink how professionals and

citizens collaborate to solve today’s global challenges. This paper has

identified land administration as an area where this crowdsourced

supported partnership could make a significant difference to levels of

security of tenure around the world. Mobile phone and personal

positioning technologies, satellite imagery, the open data movement, web

mapping and wikis are all converging to provide the ‘perfect storm’ of

change for land professionals. The challenge for land professionals is

not just to replicate elements of their current services using

crowdsourcing, but to radically rethink how land administration services

are managed and delivered in partnership with citizens. Land

administration by the people can become a distinctly 21st century

phenomenon.

REFERENCES

- Al- Omari, M. 2011. “Land Administration Systems and Land Market

Efficiency”, FIG May 2011, Morocco FIG Working Week.

- Arthur, C. 2011. “How the smartphone is killing the PC.”

Guardian Newspaper, 5th June 2011. Retrieved from

http://www.guardian.co.uk/technology/2011/jun/05/smartphones-killing-pc.

(Last accessed 10 August 2011).

- Beaumont, C. 2009. "Wikipedia ends unrestricted editing of

articles". The Telegraph. 26th August 2009. Retrieved from

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/technology/wikipedia/6088833/Wikipedia-ends-unrestricted-editing-of-articles.html.

(Last accessed 11 August 2011).

- Donovan, K. 2011. “Module 6: Anytime, Anywhere: Mobile Devices

and Services and Their Impact on Agriculture and Rural Development”,

“ICT in Agriculture” e-sourcebook. World Bank. To be published

September 2011.

- Enemark, S., van der Molen, P. and McLaren, R. 2010. “Land

Governance in Support of the Millennium Development Goals:

Responding to New Challenges,” Report on FIG / World Bank Conference

Washington DC, USA 9-10 March 2009, FIG Publication.

- Fox, K. 2011. “Africa's mobile economic revolution”, The

Observer Newspaper, 24 July 2011. Retrieved from

http://www.guardian.co.uk/technology/2011/jul/24/mobile-phones-africa-microfinance-farming.

(Last accessed 12 August 2011).

- Haklay, M., Basiouka, S., Antoniou, V. and Ather, A., 2010. “How

Many Volunteers Does It Take To Map An Area Well? The Cartographic

Journal, 47 (4), pp 315 – 322.

- Heinzelman, J., Sewell, D.R., Ziemke, J. and Meier, P. 2010.

“Lessons from Haiti and Beyond: Report from the 2010 International

Conference on Crisis Mapping”. Retrieved from

http://www.usip.org/files/resources/PB83.pdf. (Last accessed 17

August 2011).

- Laarakkar, P. and de Vries, W.T., 2010. “www.Opencadastre.org -

Exploring Potential Avenues and Concerns”. FIG May 2011, Morocco FIG

Working Week.

- UN-HABITAT. 2008. “Secure Rights for

All,” United Nations Settlement Programme (UN-HABITAT)2008, ISBN:

978-92-1-131961-3.

- Zimmerman, W. 2011. Private correspondence.

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Robin McLaren is director of Know Edge Ltd a UK based, independent

management consulting company formed in 1986. The company supports

organisations to innovate and generate business benefits from their

geospatial information. Robin has supported national governments in

formulating National Spatial Data Infrastructure (NSDI) strategies. He

led the formulation of the UK Location Strategy and has supported

similar initiatives in Kenya, Hungary, Iraq and Western Australia. He

has also supported the implementation of the EU INSPIRE Directive in the

UK and was recently a member of the UK Location Council. Robin is also

recognised as a world expert in Land Information Management and has

worked extensively with the United Nations, EU and World Bank on land

policy / land reform programmes to strengthen security of tenure and

support economic reforms in Eastern and Central Europe, Africa,

Middle-East and the Far-East.

CONTACT

Robin McLaren

Director

Know Edge Ltd

33 Lockharton Ave

Edinburgh EH12 1AY

Scotland, UK

Tel: +44 (0) 131 443 1872

E-mail:

robin.mclaren@KnowEdge.com

Web: www.KnowEdge.com

© RICS & Know Edge Ltd, 2011