Article of the Month -

November 2010

|

Social Tenure Domain Model: What It Can

Mean for the Land Industry and for the Poor

Clarissa AUGUSTINUS, UN-HABITAT

This article in .pdf-format

(16 pages, 111 KB)

This article in .pdf-format

(16 pages, 111 KB)

1) This paper is an invited paper presented at

the FIG Congress 2010 in Sydney, Australia, 11-16 April 2010, This paper

is written by Dr. Clarissa Augustinus from UN-HABITAT, with whom FIG has

had an outstanding cooperation for many years. Therefore - in addition

of being an excellent presentation on social tenure domain model - this

paper also recognises the long-term cooperation between UN-HABITAT and

FIG. Clarissa Augustinus is a social scientist who has had large impact

in the land surveying world.

Handouts

of this presentation as a .pdf-file.

Key words: Social tenure, domain model, technical gaps, Global

Land Tool Network, Tools, increased market share, pro poor

SUMMARY

Most developing countries have less than 30 percent cadastral

coverage. This means that over 70 percent of the land in many countries

is generally outside the land register. This has caused enormous

problems for example in cities, where over one billion people live in

slums without proper water, sanitation, community facilities, security

of tenure or quality of life. This has also caused problems for

countries in regard to food security and rural land management issues.

The Global Land Tool Network (GLTN), a coalition of international

partners, including FIG, has taken up this challenge and is supporting

the development of pro poor land management tools, to address the

technical gaps associated with unregistered land, the upgrading of slums

and rural land management, among other things. The security of tenure of

people in these areas relies on other forms of tenure, not individual

freehold. Most rights and claims off register are based on social

tenures. GLTN partners support a continuum of land rights, which

includes rights that are documented, undocumented, individual and group,

pastoralist, slums, legal, illegal and informal. This range of rights

generally cannot be described relative to a parcel, and therefore new

forms of spatial units and a domain model has been developed to

accommodate these social tenures, termed the Social Tenure Domain Model

(STDM) (Augustinus, Lemmen and van Oosterom: 2006). This is a pro poor

land information management system which can be used to support the land

systems of the poor in urban and rural areas, but which can also be

linked to the cadastral system so that all information can be held on

one system.

This approach will open up new markets to the land industry and it

will also be an opportunity to develop new skills and improve management

skills. STDM could make it possible for all citizens to be covered by

some form of land administration system, including the poor, thereby

improving the land management capacity of the industry, as well as

addressing upcoming challenges such as climate change. Also, STDM should

contribute to poverty reduction, as the land rights and claims of the

poor are brought into the formal system over time. It will improve their

security of tenure, increase conflict resolution, limit forced

evictions, and help the poor to engage with the land industry in

undertaking land management such as city wide slum upgrading or rural

land management. The pro poor land management approaches under

development by GLTN partners is a new way of doing business and is key

to solutions for the challenges of today and tomorrow. GLTN is focusing

on filling the gap by building the technical and governance solutions

and the capacity for the industry to use them. The technical gap covered

by STDM is in the critical path of the delivery of a number of the

Millennium Development Goals namely, Goal 1 on food security, Goal 3 on

the promotion of gender equality and the empowerment of women, and Goal

7 on ensuring environmental sustainability, including improving the

lives of slum dwellers.

1. INTRODUCTION

There are now more people living in urban areas than in rural areas

and of the total urban population of 2.3 billion in 2005 at least 810 or

39 percent live in slums (Moreno: N.D). Most people living in slums do

not have registered land rights. This means that there is no cadastre in

these areas or it does not match the de facto land tenure situation.

Cadastres do not just deliver security of tenure. As Williamson,

Enemark, Wallace and Rajabifard (2009) argue, cadastres also deliver a

land administration system. It is this system that makes the cadastre

invaluable for other purposes, such as planning, service delivery,

environmental management, city management, cost recovery, land tax, and

land management, such as slum upgrading.

In developing countries cadastral coverage is often less than 30

percent of the country (Lemmen, Augustinus, Haile and van Oosterom:

2009). This means that about seventy percent of the land in many

countries is outside of the freehold parcel based land administration

system and its land information system. This implies that people living

in these areas are often at a disadvantage, not just in regard to

security of tenure, but also in regard to such things service delivery

and land management approaches. The people in the seventy percent

generally use a wide variety of social tenures to secure their land

rights and claims. These tenures include documented, undocumented,

individual and group, legal, illegal and informal and over-lapping

rights and claims, such as those of slum dwellers, pastoralists, women

whose rights are often nested in family rights, rights of groups, and

multiple over-lapping claims in post conflict areas. This range of

tenures cannot be easily captured on conventional cadastral and land

administration systems because they are not based on unique parcel based

polygons, which are also legal evidence of land rights.

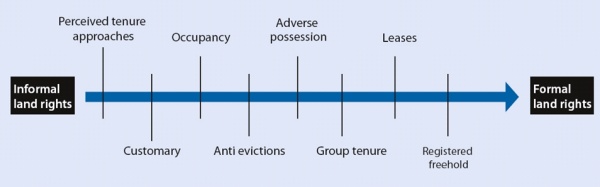

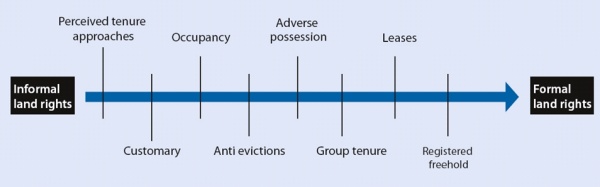

The Global Land Tool Network, a coalition of international partners,

has been promoting the idea that firstly, the variety of rights and

claims in land should be seen as a continuum of land rights which can be

incrementally upgraded over time, beginning with weak rights based on

political support, right up to full freehold, with steps in between for

informal and formal rental agreements/leases, migration routes, claims

on post conflict property and so. There will be different continuums in

different countries and different contexts. Across a continuum different

tenure systems may operate, and sites in a settlement may change status

over time. (UN-HABITAT: 2008). Secondly, the continuum of land rights

requires a new type of land information management system and land

administration system. This is required to implement the continuum of

land rights and claims and systematise them also for the purpose of land

management. The Social Tenure Domain Model (STDM) (Augustinus, Lemmen,

van Oosterom: 2006) was designed to fill this technical gap.

This technical gap was identified as early as 1998 (UNECA: 1998).

First a number of land tenure policy specialists working in Africa, Asia

and South America identified the fact that there were a range of social

tenures that could not fit with conventional land registration systems,

in terms of the types of rights held, and/or the spatial description of

the rights, and/or the land title conditions. These policy specialists

came to prominence in the 1980s and 1990s with the result that there was

little support for the use of conventional titling for customary areas

for example (Dorner: 1992; Bruce and Migot-Adholla: 1993; Migot-Adholla,

Hazell, Blarel and Place: 1991). By the end of the 1990s and the

beginning of 2000, a number of people working in the land administration

field also became convinced that conventional land administration

systems were not always appropriate for the range of tenure types that

exist such as customary areas, pastoralists and for slums (UNECA: 1998;

Barry and Fourie: 2002; Fourie, van der Molen and Groot: 2002).

Taking this further, it became clear over time that the 70 percent of

the areas outside the land registry in many developing countries, which

areas had no land administration system and land information management

system, generally meant that land management could not be undertaken in

these areas. It also became clearer over time that this impacted a wider

range of issues aside from security of tenure for the lower income

groups. That is, this gap was contributing directly to chaotic and

unsustainable cities, problems around land degradation and water shed

management, deforestation, the inability to solve land in many post

conflict environments, chaotic traffic and a proliferation of slums.

Lemmen took the lead on trying to develop solutions to fill this

technical gap from 2002 onwards, by starting to develop the Social

Tenure Domain Model (STDM) at the conceptual level (Augustinus, Lemmen,

and van Oosterom: 2006). ITC was then financially supported by the

Global Land Tool Network (GLTN) to develop the technical aspects of

STDM. GLTN is facilitated by UN-HABITAT and funded by Norway and Sweden,

which are GLTN partners. The technical development of STDM has been

undertaken with the encouragement of the President of International

Federation of Surveyors, Stig Enemark, who also committed FIG to working

towards filling this technical gap by supporting research around STDM.

The Global Land Tool Network (GLTN) is a coalition of international

organisations who have agreed on an agenda of 18 pro poor land

management tools for urban and rural areas (www.gltn.net).

Most tools are national but have rural and urban applications. These

tools are being developed by the partners not just as tools on their

own, but also linked to cross cutting issues such as gender, the

involvement of the poor users, land governance, and the need for

capacity building. The continuum of land rights (which is about the

incremental acquisition of rights over time), and STDM are two of the

GLTN tools. The partners working on STDM include UN-HABITAT, FIG, and

the World Bank and ITC, which has been at the forefront of developing

STDM. Other GLTN partners from the land administration industry in GLTN

include FAO, the Commonwealth Association of Surveying and Land Economy,

Federation des Geometres Francophone and the Royal Institution of

Chartered Surveyors. There are also other types of partners, such as

from international civil society and research and training institutions.

I will argue that by filling this technical gap, through such tools

as STDM, land managers, land administrators and land surveyors will have

an increased market share. Also they will be able to position themselves

centre stage in solving the problems of today, whether it be in regard

to climate change, or the creation of sustainable cities and the

prevention of slum growth, or ensuring food security for nations. They

will be able to do this because they will have a greater range of

options, tools and solutions to offer policy makers and politicians on

how to address the issues of the 21st century. Also, STDM could enable

professionals to deliver services to all citizens, thus addressing the

critical issue of equality and justice and thus contributing to stable

cities, and respect for the law.

The paper will also describe how the poor can benefit from STDM,

through improved security of tenure, more services, increased conflict

management and more predictability in their lives, including being able

to leave their land to their children when they die, a critical issue

for poor people. All of these will contribute to poverty reduction and

decrease the impact of human settlement related shocks, such as forced

evictions, on the vulnerable, such as women and the poorest of the poor.

The conclusions of the paper is that the land industry has a

technical gap in their tools and using current approaches cannot deliver

robust security of tenure, land information management, land

administration systems or land management at scale, particularly in

regard to developing countries, both in the rural and urban areas. This

gap is affecting the sustainability of the planet and its cities,

forests and food production among other things. The industry has taken

up this challenge but still more needs to be done and done more quickly.

2. THE URBAN CHALLENGE FOR LAND ADMINISTRATORS

Half of humanity now lives in cities, and by 2050 70 per cent of the

world’s people will reside in urban areas. By the middle of the 21st

century the total urban population of the developing world will more

than double, increasing from 2.3 billion in 2005 to 5.3 billion in 2050.

“Urban growth rates are highest in the developing world ..(which is)

responsible for 95 per cent of the world’s urban population growth”

(UN-HABITAT: 2008). However, many cities will be characterized by urban

poverty and inequality, and urban growth will become virtually

synonymous with slum formation. Indeed, Asia is already home to more

than half of the world’s slum population (581 million), followed by

sub-Saharan Africa (199 million), where 90% of new urban settlements are

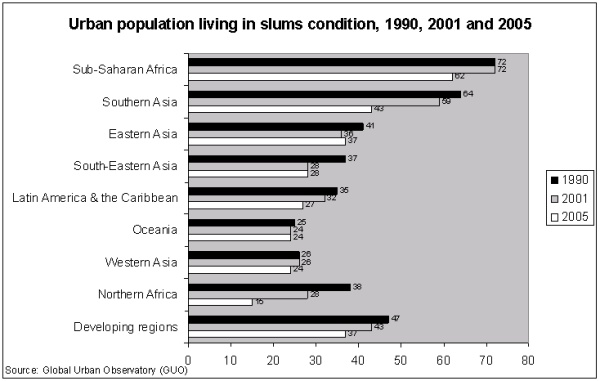

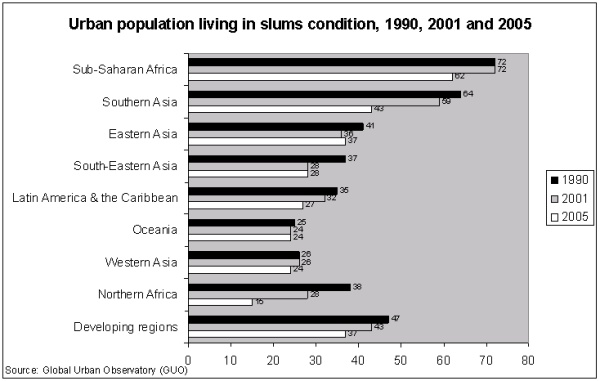

taking the form of slums. As shown in figure 1 (below), at least one

third of the urban population in the developing world lives in slum

conditions.

Figure 1: Estimated urban population living in slum condition

between 1990 and 2001 2. Moreno:

(N.D).

2.The drastic reduction of the percentage of urban

population living in slums, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa between

2001 (72 per cent) and 2005 (62 per cent) is largely explained by the

change in slum definition which now includes the use of pit latrines. A

slum household is defined as a group of individuals living under the

same roof lacking one or more of the following conditions: access to

improved water; access to improved sanitation facilities; sufficient

living area (not more than three people sharing the same room);

structural quality and durability of dwellings; and security of tenure

(UN-HABITAT: 2008).

From another angle, the space taken up by urban localities is

increasing faster than the urban population itself. Between 2000 and

2030, the world’s urban population is expected to increase by 72 per

cent, while the built-up areas of cities of 100,000 people or more could

increase by 175 per cent. The land area occupied by cities is not in

itself large, considering that it contains half the world’s population.

Recent estimates, based on satellite imagery, indicate that all urban

sites (including green as well as built-up areas) cover only 2.8 per

cent of the earth’s land area. This means that about 3.3 billion people

occupy an area less than half the size of Australia (Angel et al, 2005

cited by UNFPA, 2007). Over the next 25 years, over 2 billion people

will be added to the growing demand for housing, water supply,

sanitation and other urban infrastructure and services. What is critical

when considering this number is the order of magnitude. Close to 3

billion people, or about 40% of the world’s population by 2030, will

need housing and basic infrastructure and services. But as I will argue,

the land industry does not have all the technical tools and solutions

needed to meet this challenge and new ways of doing business and a range

of new pro poor land management tools need to be developed to meet this

challenge. The Social Tenure Domain Model is an attempt to fill one of

these technical gaps.

Finally, the Millennium Development Goal 7, Target 11, commits the

international community to achieving a significant improvement in the

lives of at least 100 million slum dwellers by the year 2020. The

attainment of even this very limited goal is not promising. Reporting on

the attainment of Goal 7, the United Nations (2007) stated that “(i)n

2005, one out of three urban dwellers was living in slum conditions –

that is lacking at least one of the basic conditions of decent housing:

adequate sanitation, improved water supply, durable housing or adequate

living space.” UN-HABITAT states that few countries are on track for

reaching Goal 7, which would imply a rapid and sustained decline in

slums. Countries that are the furthest from the slum target goals are

mostly in Sub Saharan Africa (2006). The Social Tenure Domain Model

(STDM) is a key tool which could deliver this target and the reasons for

this are described below. It should also be noted that the technical gap

covered by STDM is in the critical path of the delivery of other

Millennium Development Goals namely, Goal 1 on food security and Goal 3

on the promotion of gender equality and the empowerment of women.

3. THE CONTINUUM OF LAND RIGHTS AND THE SOCIAL TENURE DOMAIN

MODEL

Moving away from individual freehold parcel based tenure systems and

adopting a range of rights and claims in order to extend security of

tenure to more people, including the poor, implies that a new form of

land administration has to be designed. Adopting a continuum of land

rights made the land administration technical gap obvious, which

technical gap is covered by STDM.

UN-HABITAT proposed the continuum of land rights approach in 2003 and

this was further developed and adopted by the Global Land Tool Network

partners. An example of the continuum is given below (Figure 2.)

Figure 2: Continuum of land rights (UN-HABITAT: 2008)

The continuum of tenure types is a range of possible forms of tenure

which can be considered as a continuum. Each continuum provides

different sets of rights and degrees of security and responsibility.

Each enables different degrees of enforcement. Across a continuum,

different tenure systems may operate, and plots or dwellings within a

settlement may change in status, for instance if informal settlers are

granted titles or leases. Informal and customary tenure systems may

retain a sense of legitimacy after being replaced officially by

statutory systems, particularly where new systems and laws prove slow to

respond to increased or changing needs. Under these circumstances, and

where official mechanisms deny the poor legal access to land, people

tend to opt for informal and/or customary arrangements to access land in

areas that would otherwise be unaffordable or not available

(UN-HABITAT:2008).

Drawn from Fourie and Nino Fluck (2001) it is clear that the

different types of tenures found in the continuum pose a challenge to

conventional land administration systems as they are not generally

parcel based. Parcels have been the basic unit of data collection and

the linking mechanism to other information in a database. This has meant

that most information about the land in developing countries could not

be utilized in Land Information Management (LIM) systems, as the

information is generally not parcel/polygon based, let alone cadastral

parcel based.

A few examples from urban areas illustrate this:

- Privately owned land. The location of the informal settlement

does not always precisely match the cadastral parcels and is likely

to cover many properties in one spatially contiguous unit

(Cowie:1999; Jenkins et.al:1986);

- Customary land, including in urban areas, is conventionally not

parceled (Latu:N.D).

- Often the boundaries of the informal settlers’ properties do not

accord with the cadastral layout, and this can vary across the

settlement and between settlements (Jenkins et.al.:1986).

- State land. Often the state does not have an inventory of its

land. Also, often state land has not been parceled. Generally the

informal settlement boundaries do not coincide with the state land

boundaries (Jenkins et al.:1986);

Once it was recognized that freehold parcel based tenures could not

go to scale and that to supply security of tenure at scale we would have

to adopt the continuum of land rights, it became inevitable that we

would have to re-think our land administration systems, also in regard

to identifiers. This in turn would mean that we would need a new land

information management system that could handle such a range of

identifiers. Lemmen’s design of STDM has done this and gone even

further. “STDM.. is intended to provide a land information management

framework that would integrate formal, informal, and customary land

systems, as well as integrate administrative and spatial components.”

This is “..possible through tools that facilitate recording all forms of

land rights, all types of rights holders and all kinds of land and

property objects / spatial units regardless of the level of formality.”

(Lemmen, Augustinus, Haile, van Oosterom: 2009).

To conclude, once the off register social tenure arrangements of

people, particularly the poor was recognized, this meant that new

technical challenges emerged for the land industry. It is only be by

addressing these challenges that it will be possible to meet the needs

of the poor and deliver sustainable land management for the planet. In

meeting this challenge the industry will also be able to extend its

markets and position itself even better with policy makers.

4. WHAT WILL STDM DELIVER TO THE LAND INDUSTRY

By developing tools such as STDM to fill this technical gap, the land

industry will be able to go to scale and cover the whole of any country,

including the areas that are not currently covered by the cadastre,

thereby extending their markets and delivering services to all segments

of the population. This in turn will improve the professionalism with

which the land industry serves its clients. It will also make land

markets more efficient and improve our ability to address the land

management challenges of the 21st century.

4.1 Ability to go to scale

In developing countries often the coverage of the Surveyor General

and Registry land records is less than 30 percent of the country

(Lemmen, Augustinus, Haile and van Oosterom: 2009). This means that 70

percent and more of the country is outside of the freehold based land

administration system and its cadastral land information system. This in

turn means that land management in these areas is very difficult. Sub

Saharan Africa and slum areas are examples of this and are well known to

be data poor, which in turn creates problems for land managers

undertaking city wide management and slum upgrading for example. STDM

could fill that data gap and make it possible to go to scale also by

including the low income areas. This would mean that more practical

policy for the whole city could be developed and implemented. This would

be possibly for a range of reasons.

Firstly, currently countries and local governments are limited in

their ability to go to scale in terms of land records and land

management. The development of STDM data, based on the continuum of

rights tenures, would be critical for them to be able to cover their

jurisdictions systematically, so that all citizens would have some sort

of access to land and security of tenure. Local governments and their

land officials have a key role in driving land management, land use and

resource allocation and sustainable development. They have been hampered

in their job by not having sufficient data, as they are generally

reliant on the national, or federal, system to produce land parcels to

which they can link their attributes. STDM could make it possible for

these land officials to fill the data gap and assist their local

authorities to fulfil their functions better, as well as improve their

ability to deliver for all the citizens of the city, including the poor.

This could be done also because existing data sets could be over laid

with STDM data in a way that could increase the knowledge of policy

makers and planners. This would be particularly appropriate for

environmental management, both of natural resources and the built

environment, as well as the design of sustainable land use patterns.

Looking to the future, STDM could be critical for local authorities to

be able to manage the effects of climate change.

Secondly, through the introduction of STDM, low income communities

will incrementally become used to land information systems, and some of

the legal issues surrounding land. This capacity building is critical

for maintaining currency in any system, and will be of great use once

these people move into more legal systems, where land records often lose

currency because users do not see the value of updating them. Once STDM

information is available for any particular low income community it will

make it quicker and more efficient to plan the area, to upgrade it,

deliver trunk infrastructure and affordable services. It will be quicker

and more efficient because the data needed to do the initial planning

will already exist; and some capacity will already exist in the

community in regard to land and land information, making it easier to

negotiate with the community in regard to land readjustment, upgrading

and/or land acquisition and compensation. This will also make it safer

in some areas for surveyors to undertake surveys. This efficiency in

turn should make it possible for the land industry to scale up their

role in city management and improve their unit costs. Re-tooling costs

could be offset quicker through these efficiency gains.

Thirdly, STDM would make it possible to link information to other

mapping agencies and data providers which are not currently able, or

willing, to use cadastral data because of its high accuracy requirement

and/or more importantly, shortfalls in coverage. This again could

improve the scale of service delivery and land management.

Fourthly, by systematising information, including rights (formal,

informal and customary), claims, over-lapping rights and claims and

disputes, oral and written contracts, STDM could make an important

contribution to bringing peace in post conflict countries where land has

been a key driver of conflict. The role of STDM in post conflict areas

has already been identified as a need, and this is a critical new market

for the land industry. Generally land disputes are not addressed

systemically, or in time, in these situations because of this technical

gap, and STDM would also enable land dispute resolution to be scaled up,

thereby directly contributing to peace building.

Finally, STDM could generate data so a country could better measure

its coverage in regard to security of tenure. Currently indicators on

security of tenure are limited by a lack of reliable data. It would also

improve the ability of the land industry to make cross country

comparisons.

4.2 Improved professionalism

The failure of current conventional systems to deliver at the

necessary scale, because of the technical gap covered by STDM, has left

land professionals in a weaker position than they should be in regard to

policy makers. STDM, by addressing a technical gap and giving new

options, tools and solutions will make it possible for land

professionals to increase their ability to influence decision makers.

People who can assist policy makers to address the problems of chaotic

and unstable cities, impossible traffic problems, land conflict, and

climate change issues, are the leaders of the future.

Also, STDM could improve the symmetry in land information in general

which has the potential to decrease corrupt practices found in some of

the land agencies and among some land professionals. This could improve

the image of the land industry as a whole in those countries.

From another angle, STDM could increase the market of the land

industry by incorporating all sorts of transactions over the continuum

of land rights, not just freehold. It has been hard for the industry to

engage with the low income part of the market also because of the lack

of affordable pro poor land tools, particularly the documenting of

social tenures and information management systems. Market share could

also be increased through the development of a wider range of services.

STDM data could be used like cadastral data for business processes, such

as developers undertaking slum upgrading, commercial concerns delivering

to the informal economic sector of bread, alcohol, dry cleaning and so

on.

In regard to this, STDM data will include a range of types of data

including dirty data, legal and informal data. The land industry will

need to adjust to this range of data, and how to use it as over laid

data, in order to improve land use planning, land management and

environmental planning. Non specialised people will also produce some of

the data. New skills will be needed in interpretation of the data and

the management of the results. New skills will also be needed to manage

a different level of data gatherers. Some types of risk will decrease

and other risks will emerge, and these will have to be managed. A new

type of land information manager and land manager is likely to emerge to

use STDM, which will need capacity building and resources.

A specific example of these potential new roles and opportunities

relates to land and the courts. Many countries in the world have huge

case back logs of land cases, or cases which have underlying issues

related to land. STDM can identify and describe the range of land

disputes that exist, and at an earlier stage prior to entering court,

thereby decreasing the number of cases in court and increasing the

number of cases that could be solved through Alternative Dispute

Resolution mechanisms. This has always been a crucial role of surveyors

and may strengthen the role and scope of community leaders, para-legals,

government officials, surveyors and lawyers involved in mediation.

Finally, the ability of the land industry to deliver to all citizens,

including the poor, and not just the rich, middle class and commercial

classes as is the case currently in many countries, could in time

improve the equality and social justice that is often missing in the

land sector. Until the technical gap currently covered by STDM is

filled, this issue will continue to block the attainment of the goal of

land reform.

4.3 More efficient land markets

By using STDM the land markets should operate more efficiently as

well. This efficiency will come about for a number of reasons. Firstly

there will be more symmetry about land information to all stakeholders,

increasing transparency for buyers. Secondly, both the formal and

informal land markets will be able to be placed on the same land

information system, as the STDM can also be linked to the cadastral

information system, improving symmetry of information even more.

Thirdly, because of the availability of STDM data it will be easier for

negotiations to take place on land that has been frozen by family and

neighbourhood disputes and/or deceased estates. This will be of

particular importance in Muslim countries where shared inheritance is

practiced.

Fourthly, land acquisition for development will be easier because

data will be available from the outset, hopefully linked to pro poor

compensation packages. This is particularly important in peri-urban

areas where urban development is often concentrated, yet land records

reflecting the legal reality are often the weakest. Fifthly, because of

data availability, land use planning will be more efficient and

realistic and hopefully affordable. Sixthly, one of the major delays in

land documentation (registration) is adjudication. STDM data will make

systematic adjudication more efficient as it could build on existing

data and potential disputes can be identified before hand.

Seventhly, land disputes and the type of dispute will be known to all

buyers, who will be able to factor this into value and price. Eighthly,

through the STDM system which supports a range of rights and not just

freehold, buyers will be able to better assess the security of tenure of

different documents and the value of the land will more accurately

reflect the land market. Ninthly, land use conflicts will be able to be

identified at an earlier stage and dealt with, with the result that

there could be less land related court cases. Court cases can freeze

land for years, so STDM may well free up this land earlier. Also, since

STDM will provide more realistic information which will be reflected in

the land value, the market will indirectly influence quicker resolution

of land disputes.

Tenthly, by expanding the conventional systems and formal markets to

link to STDM, the other forms of tenure, and the informal markets, the

supply and demand currently focused on freehold, which causes economic

distortions and increases corruption, is likely to be re-set at a new

position. All this will improve the functionality of the land markets.

Finally, surveyors and information managers will have to manage the

transition of the land and data, including STDM data, through different

stages of the continuum of land rights in a way that “..anticipates the

complexities of a fully developed formal land market.” (Williamson,

Enemark, Wallace, Rajabifard: 2009).

5. WHAT WILL STDM DELIVER TO THE POOR

Currently, most poor people are not covered by a land administration

system and its linked land information management system. This means

that they do not benefit from these systems in regard to tenure

security, planning and service delivery, slum upgrading, resolution of

disputes and so on. STDM would make it possible for a country and/or

local government to go to scale and include low income people in their

information systems and in their land delivery approaches. This would

have a direct impact on the quality of life of the poor and on poverty

reduction. It would also have a direct impact on the stabilisation and

governance of cities, also through the empowerment of the poor. This is

because it is not possible to create sustainable cities if the poor are

not part of the solution.

5.1 Improved Security of Tenure at Scale

Many poor rely on informal and/ or customary land rights, which are

often not administered and documented systematically. STDM is designed

as a pro poor land information management system to underpin the types

of social tenures which the poor use to give them security of tenure.

STDM could make it possible to document systematically and upgrade these

tenures over time along a continuum of land rights. Documentation of

some kind available to the poor, which is affordable and relevant to

their situations and social tenures, will increase their security of

tenure in terms of use rights and land ‘rights’.

STDM will be used to document land rights, claims and over-lapping

rights prior to conventional adjudication, planning, surveying and

registration, which is expensive, takes a lot of time and normally is

out of the reach of the poor. Also the STDM information will include

both de facto as well as de jure land ‘rights’ and use rights on the

same system. The availability of data and on the same system will mean

two things. Firstly, this will enable more effective, efficient and

affordable city wide land use planning, which has often suffered from

data deficiencies. This will make it possible to service slum areas more

easily and link it to the trunk infrastructure, also because it will

give the poor an address, making it possible to undertake cost recovery

on services. This will increase service delivery to the poor, such as

water. Secondly, a major cost and time issue related to land

registration is the information produced during adjudication in formal

land titling processes. The STDM data will make adjudication, surveying

and documentation at some later point cheaper, more efficient and faster

thus making it possible for the poor to be brought into the formal

systems earlier, thereby increasing their security of tenure along the

continuum of land rights faster.

The STDM will hold information on the rights and claims of the poor

and the information from the cadastre, state asset register, and

municipal asset register (where this information is available).

Knowledge of the legal status of the land will limit evictions. A common

problem has been that state officials allocate land to investors and

developers which is already occupied by the poor, because there is no

information about land rights on their land information system. By

linking the cadastral information to STDM information it will be

possible to ascertain whether the land is already occupied and claimed

and is not empty. Mozambique has used this kind of approach effectively.

Also, the poor will be able to identify the legal owner of the land they

occupy with whom they can negotiate. Renters in the slum could be

protected during this process as their information will also be

identified on the STDM -their rights and claims as well as that of the

‘owners’ would be identified. NGOs in the Philippines have used this

kind of approach to effectively negotiate with land owners. An operating

STDM could also make it possible for the poor to argue for compensation

when land acquisition is undertaken, and help to standardise

compensation procedures, as they could be based on STDM information.

From another angle, slum upgrading currently tends to be project or

community focused because of a lack of city wide land information and

land management. An STDM type tool is in the critical path of city wide

slum upgrading and the provision of planning and service provision to

the poor at scale. City wide land management will be possible once the

entire city is covered with conventional cadastral information

management system linked to the STDM information, as the information

will be at scale. Not only will it be possible to work out more

affordable and efficient options, but it will also be possible to

implement the policies better. It will be possible to carry out improved

policy planning and implementation for the city in general, as well as

road, trunk infrastructure, services and community facilities, as well

as environmental management. This is turn will impact the lives of the

poor through for example, improved transportation (the poor often spend

hours commuting); cheaper water supply (the poor pay more than the rich

generally for water); more accessible health facilities (the poor often

have to travel hours to get medical attention and are more reliant on

hospitals as the rich tend to use private doctors).

Finally, a key issue for the poor is whether their children can

inherit the land they are holding. STDM could make it easier for the

poor, particularly women, to inherit the land as it could provide the

necessary information for the resolution of disputes, as well as supply

some evidence of rights and claims which could under the right

conditions enable forums, such as courts, to make better and less

arbitrary decisions.

5.2 Improved Quality of Life

People who do not have access to basic services, who do not have

security of tenure and who constantly experience the threat and fear of

losing their homes need improved quality of life. This is the case for

many inhabitants of the slums. Their quality of life is directly related

to secure access to land which is serviced.

STDM can contribute to poverty alleviation through improving poor

people’s access to a key asset for sustainable livelihoods, namely

access to land and security of tenure. Also, through creating a system

to underpin affordable land tenure options, it can reduce the cost of

access, planning and servicing of the area, thereby putting more money

in the pockets of the poor.

STDM can contribute directly to slum dwellers’ quality of life

through improved service provision because it will make it possible to

create a large scale detailed map of the entire jurisdiction, be it a

local authority, area of a para-statal responsibility for water or

electricity, or under the responsibility of a national department, such

as education. This could mean that slum dwellers, who have often been

excluded from service delivery, could be able to more easily receive

services including community facilities. Often slums cannot be serviced

with water, refuse clearing, electricity, schools, clinics because the

slum area is not on the ‘official map’ of any of the line departments

responsible for education or health for example, or even the local

government responsible for refuse, electricity etc. For example in

Kenya, the Department of Education does not address schooling in slum

areas as they are in unplanned areas, and informal schools are the only

option for young slum residents. With STDM data and on one system, it

could be possible to undertake planning, service delivery and the

delivery of community facilities. This would have an enormous impact on

the quality of life of the slum residents.

Also, increased security of tenure means that people invest more in

their homes. The quality of the housing stock in the slums is likely to

improve, which will impact residents quality of life. People will most

likely replace leaking roofs, mud walls which cave in to overflow

streams and poorly built pit latrines once they have a form of security

of tenure. This will contribute directly to their quality of life.

From another angle, poor people generally rely on neighbours to see

them through hard times. When slum residents are evicted they not only

lose their land and homes, but they also lose their networks. This means

that they become more vulnerable to shocks, such as natural disasters,

loss of employment during economic down turns, or the loss of the bread

winner to HIV/Aids and other diseases. These shocks are known to force

people into becoming the poorest of the poor where it is difficult to

survive. Because STDM assists poor people’s security of tenure prior to

all the formal procedures, it may be possible for people to remain

resident within the same neighbourhood for longer time periods, thereby

keeping their safety nets in place and limiting the impact of shocks on

the poor and vulnerable.

Finally, the more information the poor have about the land they live

on, the more they will be able to plan, instead of surviving day to day

never knowing when they are going to be evicted. STDM can supply that

kind of information to make it possible for the poor to better plan

their lives.

5.3 Improved Governance and Empowerment

Information is power. STDM can make information available at a lower

level in a more simple fashion, such as on land tenures, so that poor

people can both access it and understand it. This should improve

transparency about land allocation, acquisition, inheritance and

transfers -for example from government to private developers. The poor

may not be as much at the mercy of the syndicates which sometimes

operate in the public and private sectors. This can contribute to

decreasing evictions and limiting corrupt practices. STDM and the land

documents linked to it can increase democracy by building capacity in

the poor, in terms of knowledge transfer about the wider land setting,

and empower them to negotiate better with other stakeholders, such as

private land owners and local authorities. Increased negotiation

capacity by the poor with other stakeholders should mean that it could

be possible to undertake more sustainable planning and land management,

such as land readjustment, as the poor take ownership and responsibility

for their settlements.

Many women are disproportionally affected by poverty, and this is

directly linked to their access to land. On average women have fewer

rights over land than men, and poor women particularly suffer from this

problem. The experience of the Huariou Commission and Slum Dwellers

International, both partners in GLTN, have shown that women play a key

role in successful slum upgrading exercises. STDM can contribute to

overcoming gender disparity as it can also hold the record of women’s

land rights, which are often nested within family rights, thereby

empowering them to claim these rights and participate in land management

operations.

Land and conflict are often linked, and STDM can contribute to

improved land governance as STDM information can be used for dispute

resolution between neighbours, between residents and the state, and

residents and local authorities, as it could show rights, claims, and

over-lapping rights and claims. Having such information and at scale may

also make it possible to develop typologies of conflict and create

procedures around their resolution. For example, disputes between

neighbours over boundaries can probably be solved locally by community

leaders with sufficient information and power. Disputes between

communities and private land owners will need to be solved through other

means. That is, STDM can be crucial to a process whereby land disputes

can be recorded and fed into a dispute resolution process. In this way

STDM can contribute to conflict management in cities, which will in turn

have an impact on violence and crime in cities, as often this is linked

to land. That is, STDM could contribute to social stability.

This together with improved governance and respect for the rights of

all citizens in the city, as well as tools which the poor can use to

document their land, can build the rule of law. Too often the regulatory

framework associated with land has been damaged and distorted. STDM can

make it possible to strengthen the rule of law around land.

Finally, STDM can make full coverage of both the rich and the poor

land rights and claims possible, and place the information on the same

system. This would facilitate the better allocation of resources and the

redistribution of land and use rights for improved sustainable

development.

6. CONCLUSION

The urban challenge is enormous. Cities are already struggling to

cope with the impact of urbanization and this is set to increase in many

countries, especially in Africa and South East Asia. Managing the

expected increase in the geographic area of cities will require large

scale investment to ensure that urban development is not chaotic. The

amount of shelter and land delivery needed over the next few decades, to

ensure that there is adequate housing for all, and for the world to move

to sustainable urbanization, is daunting. Yet a review of the global

position in regard to shelter delivery indicates that the agenda is not

prominent enough and urgent action is needed to get a focus back on this

sector. While, through the work of GLTN partners and others, the

implementation of pro poor large scale land tools has started, much more

needs to be done to go to scale.

The conclusion of the paper is that there is a major technical gap

which needs to be filled and this has been shown relative to the urban

areas. (Rural examples could have been used for the same purpose as GLTN

and STDM are designed to serve national needs -rural and urban). Using

current approaches cannot deliver robust security of tenure, land

information management, land administration systems or land management

at scale, to a large part of the land in developing countries, both in

the rural and urban areas. This gap is affecting the sustainability of

the planet and its cities, forests and food production, among other

things. Early work is being done to fill this gap by the land industry

and this work should increase its market share and have a major impact

on the lives of the poor and the places they live in. The industry has

taken up this challenge but still a lot more needs to be done and done

much more quickly. Finally, the technical gap covered by STDM is in the

critical path of the delivery of a number of the Millennium Development

Goals namely, Goal 1 on food security, Goal 3 on the promotion of gender

equality and the empowerment of women, and of course Goal 7 on ensuring

environmental sustainability, including improving the lives of slum

dwellers.

REFERENCES

- Angel, S., Sheppard, S. C. and D. L. Civco, (2005) The Dynamics

of Global Urban Expansion, Washington, D.C.: Transport and Urban

Development Department, the World Bank.

- Augustinus, C., Lemmen, C. and P. van Oosterom, (2006) Social

tenure domain model: Requirements from the perspective of pro poor

land management, Proceedings of 5th Regional Conference on Promoting

Land Administration and Good Government in Accra, Ghana 8-11 March,

2006. (http://www.fig.net/pub/accra/papers/ps03/ps03_02_lemmen.pdf)

Barry, M. and C. Fourie, (2002) Wicked problems, Soft systems and

Cadastral systems in Periods of Uncertainty, Survey Review,

36(285):483:496, Paper presented at CONSAS, Cape Town, South Africa,

12-14th March, 2001.

- Bruce, J. and S. Migot-Adholla, (eds.) (1993) Searching for

tenure security in sub-Saharan Africa, Kendall/Hunt, Dubuque, Iowa.

- Cowie, T. (1999) The development of a local land records system

for informal settlements in the Greater Edendale Area, MSc thesis,

University of Natal.

- Dorner, P. (1992) Latin American Land Reforms in Theory and

Practice: A Retrospective Analysis, University of Wisconsin Press.

- Fourie, C., P. van der Molen and R.Groot (2002) Land management,

land administration and geo-spatial data: Exploring the conceptual

linkages in the developing world, Geomatica, 56(4).

Fourie, C. and O. Nino-Fluck, (2001) An Integrated geo-information

system for decision-makers in Africa, Survey Review, 36.

- Jenkins, D.P., D.A.Scogings, H.Margeot, C.Fourie and P.Perkin,

(1986) Investigation of the Emerging Patterns of Zulu Land Tenure

and the Implications for the Establishment of Effective Land

Information and Administrative Systems as a Base for Development.

Project Report, H.S.R.C.

Latu, T.S. (N.D.), Modeling a land information system for freehold

and customary land tenure systems, Department of Land Information,

RMIT Centre for Remote Sensing and GIS, Occasional Paper Series, No.

95/1.

Lemmen, C., Augustinus, C., Haile, S. P. van Oosterom, (2009) The

Social Tenure Domain Model

Subtitle: A Pro Poor Land Rights Recording System, GIM.

- Mighot-Adholla, S., Hazell, P., Blarel, B. and F.Place, (1991)

Indigenous land rights systems in sub-Saharan Africa: A constraint

on Productivity? The World Bank, Economic Review, 5(1):155-175.

- Deininger, K., (2003) Land Policies for Growth and Poverty

Reduction, World Bank and Oxford University Press.

- Moreno, E., (N.D) Living with Shelter Deprivations: Slums

Dwellers in the World, City Monitoring Branch, UN-HABITAT.

- United Nations, (2007) The Millennium Development Goals Report

2007, New York, United Nations.

- United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, (1998) An

integrated geo-information (GIS) with emphasis on cadastre and land

information systems (LIS) for decision-makers in Africa. Background

report of Expert Group Meeting, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 23-26

November, 1998.

- UN-HABITAT, (2008) Secure Land Rights for All, Nairobi,

UN-HABITAT.

- UN-HABITAT, (2008) State of the World’s Cities 2008/9:

Harmonious Cities, London, Earthscan.

- UN-HABITAT, (2006) State of the World’s Cities 2006/7: The

Millennium Development Goals and Urban Sustainability, London.

- UN-HABITAT, (2003) Handbook on Best Practices, Security of

Tenure and Access to Land, Nairobi, UN-HABITAT.

- Williamson, I., Enemark, S, Wallace, J. and A. Rajabifard (2009)

Land Administration for Sustainable Development, Redlands,

California, ESRI Press Academic.

- www.gltn.net

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Clarissa Augustinus is Chief of the Land, Tenure and Property

Administration Section, Shelter Branch, Global Division, in UN-HABITAT.

Key driver of the Global Land Tool Network, focusing on innovative pro

poor land tools. Network has over 40 international and regional

partners, including multi-laterals such as the World Bank and FAO,

bi-laterals such as Norway and Sweden the key funders, professional

organizations, such as the International Federation of Surveyors,

Commonwealth Association of Surveying and Land Economy, Federation des

Geometres Francophone, Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors,

training and research institutions and international civil society.

Previously Senior Lecturer, School of Civil Engineering, Surveying and

Construction, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, focusing on

Land Management. International consultant on land management and

administration from an institutional perspective. Author of 3 chapters

in books, and over 44 papers. Ph.D in Social Anthropology on customary

and informal land tenure in an informal settlement in Africa.

CONTACTS

Dr. Clarissa Augustinus

UN-HABITAT

P.O. Box 300300

00100 Nairobi

KENYA

+ 254 20 7624652

clarissa.augustinus@unhabitat.org

www.gltn.net

|