Article of the Month - February 2019

|

From a Property Tax to a Land Tax – Who Wins,

Who Loses?

Peter WYATT, United Kingdom

Peter Wyatt

This article in .pdf-format

(24 pages)

This paper has passed the FIG peer review and will be

presented at the FIG Working Week 2019 in Hanoi, Vietnam. The paper

looks at some of the consequences of switching from recurrent real

estate taxes that are based on improved values to one that is based on

the value of unimproved land. Focusing on one local authority area in

the south east of England, the paper answers the following questions:

how might the valuation of unimproved land be undertaken in a developed

economy where most transactional evidence relates to improved land, and

what are the revenue implications of switching from an occupier tax to

an ownership tax? In particular, who are the winners and losers and

does expansion of the tax base to include agricultural land uses make

much difference?

SUMMARY

Whilst the theoretical case in favour of a tax on the unimproved

value of land (a land tax) is well established, examples of its

implementation in practice are relatively few in number. Where a

land tax is levied, it is often part of a suite of land and property

taxes that includes transfer taxes, wealth taxes betterment and

recurrent taxes on improved land. Rarely is a land tax the sole

mechanism for taxing real estate. Yet there is no shortage of land

tax supporters, even in countries where other forms of real estate tax

have a long history. England is one such country, where real

estate taxes have existed since the 17th century in one form or another.

Despite strong lobbying at the beginning of the 19th century,

governments on the left, right and in the centre ground of political

discourse chose not to switch to a land tax.

In the land tax debate throughout this period, there was an absence

of empirical research to underpin the positions adopted by either

proponents of a land tax or defenders of the status quo. It was not

until 1964 that a small pilot exercise was undertaken to investigate the

implications of introducing a land tax in England. This seems odd

given that frequently cited criticisms of a land tax centre on its

practical difficulties. This paper, therefore, looks at some of

the consequences of switching from recurrent real estate taxes that are

based on improved values to one that is based on the value of unimproved

land. Focusing on one local authority area in the south east of

England, the paper answers the following questions: how might the

valuation of unimproved land be undertaken in a developed economy where

most transactional evidence relates to improved land, and what are the

revenue implications of switching from an occupier tax to an ownership

tax? In particular, who are the winners and losers and does

expansion of the tax base to include agricultural land uses make much

difference?

1. INTRODUCTION

Whilst the theoretical case in favour of a tax on the unimproved

value of land (a land tax) is well established, examples of its

implementation in practice are relatively few in number. Where a

land tax is levied, it is often part of a suite of land and property

taxes that includes transfer taxes, wealth taxes betterment and

recurrent taxes on improved land. Rarely is a land tax the sole

mechanism for taxing real estate.

Yet there is no shortage of land tax supporters, even in countries

where other forms of real estate tax have a long history. England

is one such country, where real estate taxes have existed since the 17th

century in one form or another. Despite strong lobbying at the

beginning of the 19th century, following the publication of Henry

George’s Progress and Poverty, governments on the left, right and in the

centre ground of political discourse chose not to switch to a land tax.

It is interesting to note that, in the land tax debate throughout

this period, there was an absence of empirical research to underpin the

positions adopted by either proponents of a land tax or defenders of the

status quo. The debate was a political, ideological and

theoretical one (McGill and Plimmer, 2004). It was not until 1964

that a small pilot exercise was undertaken to investigate the

implications of introducing a land tax in England. This seems odd

given that frequently cited criticisms of a land tax centre on technical

difficulties, and particularly the need to value unimproved land even

though most transactional evidence relates to improved land. It

would be useful to investigate these difficulties to see if

circumstances have changed. This paper, therefore, looks at models

of the possible consequences of switching from recurrent real estate

taxes that are based on improved values to one that is based on the

value of unimproved land. Focusing on one local authority area in

the south east of England, the paper seeks to answer the following two

questions:

- How might the

valuation of unimproved land be undertaken in a developed economy where

most transactional evidence relates to improved land?

- What are the revenue

implications of switching from an occupier tax to an ownership tax?

In particular, who are the winners and losers and does expansion of the

tax base to include agricultural land uses make much difference?

2. THE THEORETICAL CASE FOR A LAND TAX

The theoretical case for a recurrent tax based on the unimproved

value of land is well documented. Classical and neo-classical economists

such as Adam Smith, David Ricardo, John Stuart Mill and Alfred Marshall

demonstrated that the economic rent (and its capitalised equivalent,

value) which land is able to earn over and above the return generated

after optimally employing labour and capital is determined by its

scarcity and its location, neither of which are derived from any

productive activity on the part of the landowner. Land value is,

therefore, the price of monopoly: the scarcer and less substitutable a

parcel of land is, and the more attractive the location in relation to

the market and factors of production, the more valuable the land.

Land use planning and regulation, which are not the result of

landowner action, create further scarcity, increasing the value of land

in specific locations. At the land parcel level, the grant of

permission to develop land (including changing its use) can generate

substantial increases in land value. In societies where

governments provide infrastructure, services and amenities, landowners

may also benefit from value uplift as a direct result of this publicly

funded investment. Land value is argued to be, therefore, the

creation of the community and expresses, in financial terms, the right a

community has in land held by an individual.

Who receives economic rent depends on who owns the land and the

mechanisms in place to collect it. Debate over entitlement to

these legal rights over land (including the right to use, exclude

others, reap economic benefit, transfer, inherit, etc.) has a recorded

history of at least four centuries: whether such rights should be

privately owned and state protected (Locke, Bentham) or publicly owned

(Rousseau, Marx). As global population and the rate of

urbanisation increase, pressure on land resources grows, and the

philosophical debate over land rights intensifies with socioeconomic

concerns over access to and distribution of land and its associated

wealth (de Soto, 2000).

In countries where property rights are held privately, the

combination of private property rights and monopoly land value creates

two social costs: unearned land value (or wealth) and unequal

distribution of that wealth. One means of recovering unearned land value

is a tax. Adam Smith argued that a tax on land value would not

harm economic activity and would not increase land rents. The idea of a

recurrent tax on land value has been propounded ever since with 19th

century liberal economist Henry George making the most well-known case

for a single tax on land value (George, 2005). However, a single

tax on land that replaces all other taxes has not been introduced, the

most likely reason being that a wealth tax on such a scale could

dramatically reduce land values. Instead, the idea of a land tax

as a single land and property tax has been advocated, but these are

usually at low rates and capture only a small fraction of value.

Other reasons why land tax is regarded as beneficial:

- It does not distort choices as to how much to invest in

improvements (Dye and England, 2010)

- It can encourage optimum use of land (Commission on Local Tax

Reform, 2015 Vol 3, p.26-7) and reuse of vacant land (Lyons Inquiry

into Local Government, 2005, p.76)

- By raising the holding cost of land, it may discourage land banking

and speculation and encourage development

- It may encourage denser development (subject to planning) and

therefore limit urban sprawl

Although the theoretical case for taxing land is well established,

there are legitimate reasons for taxing improvements too.

Occupiers of improved land consume local services and benefit from

local amenities and this service provision needs funding, leading to

a case for taxing the value of improvements. Mirrlees et al (2011)

suggest that land and improvements should be thought of as distinct

bases for taxation, given that the investment in improvements does

not always correlate with the use of services. In reality,

many countries’ taxes are levied on their combined value and

therefore have what could be considered as a dual role: tax on

services used (waste collection, road repairs, etc.) and value of

land in the basis of its existing (i.e. unimproved) use. They

also argue that only residential improvements should be taxed since

business premises are an input into the production process so taxing

them would distort choices firms make about production (Mirrlees et

al, 2011:376).

Lichfield et al stressed the need to ensure land taxation is

compatible with development planning and Connellan (2004) explores

the moral and ethical rational for land taxation, as well its

practical operation in the UK. Dunne (2005) and Dye and

England (2011) also consider the practical issues associated with

land taxation. Lyons (2011), Lyons and Wightman (2013) and

Wightman (2013a and 2013b) investigate the potential for

implementing a land tax in the British Isles and in Ireland. More

recently, Corlett et al (2018) suggest replacing Business Rates and

Stamp Duty Land Tax on commercial transactions with a commercial

landowner levy, in other words a land value tax on owners.

3. LAND AND PROPERTY TAXATION

Despite the theoretical case for a tax on the unearned wealth

arising from land ownership, an all-encompassing land tax is a

rarity. Instead, a land tax usually sits alongside a gamut of

direct land and property taxes which can be classified in different

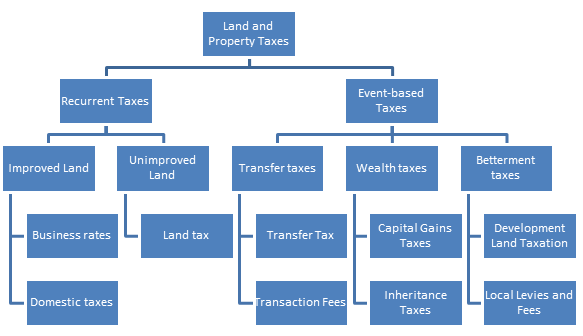

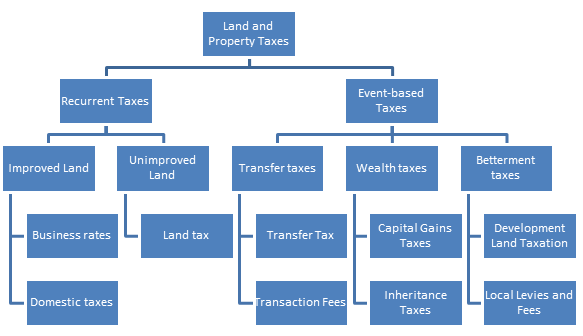

ways. Figure 1 categorises them as recurrent (usually annual) taxes

and event-based taxes. These taxes will directly affect land

value as the cost of the tax can be capitalised and deducted from

the price paid for land. In addition to these are indirect

taxes on land and property: VAT, which may be charged on the sale or

lease of commercial property; and income tax and corporation tax,

which are charged on rental income and profits from property

investment. These are less likely to be directly reflected as

capitalised deductions from land value as their incidence and

magnitude are dependent on taxpayer decisions and status.

Figure 1 – Direct land and property taxes

Recurrent land and property taxes are usually assessed with reference

to value of unimproved land (a land tax) or improved land (a property

tax) and levied as a percentage of either the annual (rental) or the

capital value of the land parcel. Event-based taxes include

transfer taxes, wealth taxes and betterment taxes. Table 1 summarises

the key attributes of each of these taxes.

Table 1 – Key attributes of land and property taxes

|

Type of tax

|

Description

|

Recurrence

|

Liability

|

Incidence

|

| Recurrent tax |

A tax usually levied to help pay for local services |

Annual |

Occupiers or owners |

Occupation or ownership |

| Transfer tax |

% price agreed on transfer of ownership |

On transfer |

Owners |

Transfer |

| Betterment tax |

On increase in value attributable to granting of development

rights |

On grant of planning permission or commencement of

development |

Owners

|

General, scheme specific |

| Capital gains tax |

Accruing to property asset(s) whose value has appreciated

over time |

On realisation of chargeable capital gain |

Owners |

Wealth, Transfer |

| Inheritance tax |

On the value of property owned at death |

On death |

Owners |

Wealth, Transfer |

In England, all attempts to tax value arising specifically from the

grant of consent and the exercise of development rights, of which there

have been four since 1947, have been short-lived and resulted in failure

both in revenue terms and in bringing forward land for development.

What exists in terms of event-based land and property taxes is transfer

tax, capital gains tax, inheritance tax, and local betterment taxes (in

the form of ‘planning obligations’ and infrastructure levy).

England has two forms of recurrent land and property tax that are both

based on the improved value of land. These are Council Tax, which is

levied on domestic properties, and Business Rates levied on non-domestic

properties. The taxable entity for both of these taxes is the occupier

in the first instance, although owners become liable if the property is

unoccupied.

Council Tax is based on capital values of dwellings. Each local

authority administers and collects the tax and decides how tax revenue

is spent. There are eight council tax bands, from A (lowest) to H

(highest). These bands are based on estimations of the market value of

residential properties as at 1 April 1991. Local councils set the band D

tax rate, with the charges for properties in other bands being a fixed

proportion of that band D charge. Business Rates are based on

annual rental values and are revalued on a five-yearly basis. The

valuations are undertaken by a central government agency and the tax

rate is set by central government each year, but individual local

councils administer and collect the tax. Business Rates raise more

revenue than council tax despite a far smaller tax base. There are

a range of reliefs from these taxes; the main one is agricultural land

and buildings. Table 2 summarises the characteristics of Council

Tax and Business Rates.

Table 2 – Attributes of Council tax and Business Rates

|

Council Tax

|

Business Rates

|

| Based on value bands |

Based on spot values |

| Based on capital values |

Based on annual rental values |

| Local authorities set rate |

Central government sets rate |

|

Tax is collected by local authorities

|

| Occupiers liable (owners if property is empty) |

|

Based on 1991 values and never been revalued

|

Revalued every five years (seven years in one case)

|

| Various reliefs and exemptions, the main one being 25%

discount for single occupancy |

Various reliefs and exemptions, the main one being exemption

for agricultural land and woodland |

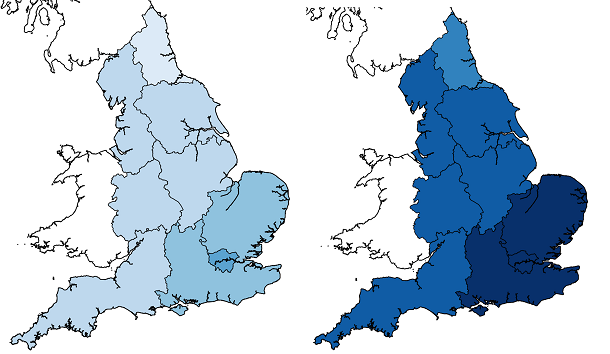

Council Tax is regressive in two ways. First, the tax rate declines

when moving from lower to higher value bands. Roughly speaking the

percentage increase in bills between bands is half the percentage

increase in property values (Hills and Sutherland, 1991). Second,

the absence of revaluations means that increases in land value are not

being taxed and geographical shifts in land value are not reflected.

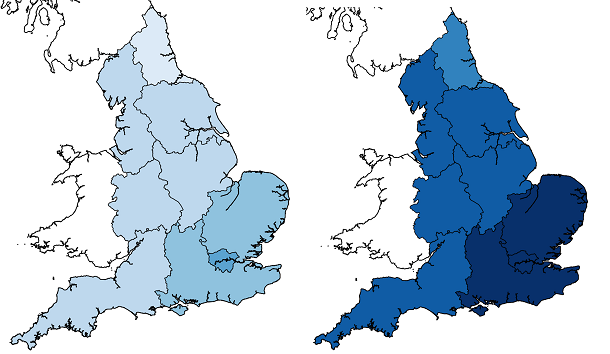

For example, in 1995 the mean house price in the north east of England

was 29% below the mean for England and the south east was 20% above.

By 2017 the north east was 47% below and the south east was 25% above.

Figure 2 shows that values have shifted from the north to the south and

this is not reflected in the 1991 values. Leishman et al (2004)

looked at alternatives to the Council Tax system and Corlett and

Gardiner (2013) provide a critique of the Council Tax and suggests

replacing it with a progressive property tax. Business Rates are a

tax on land and improvements and therefore it is, at least in part,

economically inefficient as it taxes a production input. There are

also some discounts for empty properties and this is acts as a

disincentive for reuse.

Figure 2 – Mean house prices in years ending Dec 1995 and Dec 2017

(dark shades are higher Council Tax value bands and light shades are

lower)

4. IMPLEMENTING A LAND TAX AS A REPLACEMENT FOR A PROPERTY TAX

There are a number of issues that need to be considered when deciding

whether to introduce a land tax as a replacement for an existing

property tax.

The first issue is the windfall loss incurred by owners of land as the

tax base shifts from occupiers to owners. The main losers when switching

from an occupation tax such as business rates to a land tax would be

land-extensive businesses (IPPR, 2005). A broader, more inclusive tax

base means that tax rates for everyone can be lower, but the UN (2011)

notes that taxation of agricultural land or forest land can be

politically sensitive. This may explain to some degree why many

countries with a land tax apply special reliefs to agriculture, through

full or partial exemptions, or lower tax rates (Norregaard, 2013).

Also, the impact on other taxes needs to be carefully considered.

Further, in most countries special provisions exist for heritage assets,

which are deemed to require protection.

Second, in their review of international literature, Gibb and Christie

(2015) note that there is a risk that introducing a land tax may

initially lead to significant land value reductions as a result of the

capitalisation of future tax liabilities into the value of land.

This could have significant implications for economies that rely on the

wealth stored in property values as collateral for debt. To

counter such a fall in values, a transitional arrangement might be

appropriate, perhaps phasing in the land tax or offering compensation to

those initially affected.

Third, because a land tax is usually levied on owners, this can cause

confusion over the purpose of the tax. Local taxation is often

regarded as a benefit or service tax to pay for the provision of local

infrastructure, services and amenities. Therefore, occupiers of

land, together with improvements to the land, would be the appropriate

taxable entities. However, if the tax is also in part a wealth tax

designed to capture uplift in value resulting from the provision of

local infrastructure, services and amenities, then the landowner would

be the appropriate taxable entity. In reality, a land tax is a

hybrid benefit tax and wealth tax. The confusion stems from the

fact that the tax is assessed by reference to values. Is the tax

based on values to capture greater taxes from those with higher value

properties or is it based on values because those living in higher value

properties will use infrastructure, services and amenities more?

Relatedly, the level of tax liability may not necessarily be correlated

with ability to pay, so a mechanism might be required for taxpayers to

defer payment until sale.

Turning to the more technical aspects associated with a land tax, it

requires a register of land ownership that records legally identifiable

boundaries and permitted land use and development rights for all sites.

England does not have such a legal cadastre. Moreover, England has

a plan-led discretionary system for allocating land use rights, which is

different from zoning systems that delineate permitted uses on an

area-by-area basis, conveying development rights to landowners without

the need for detailed approval. In a zoning system the assessment of

permitted use is more straightforward than a plan-led discretionary

system.

It may be difficult to value unimproved land. This is because

valuations rely heavily on the availability of evidence to support

assessed values, but evidence of sales of unimproved land, particularly

within urban areas is often difficult to find. An alternative is

to use an approach known as the ‘residual’ method, whereby build costs

and other adjustments are subtracted from the total value of the

development to arrive at a ‘residual’ land value. The approach is

used later in this paper, but it is worth noting here that it can

produce confounding results. For example, take two dwellings

side-by-side. One is three-storey and developed to highest and

best use (market value = £1m, build and other costs = £0.5m, so land

value = £0.5m), the other is two-storey (market value = £0.7m, build and

other costs = £0.3m, so land value = £0.4m). The land value (and

therefore the tax) of the first property is higher. The

relationship between property value and build cost is penalising the

development of land to highest and best use, which is counterintuitive

as far as a land tax is concerned.

This problem could be addressed by valuing the land on which the

two-storey property is constructed at its ‘highest and best use’, in

other words assuming that it is developed to three-storeys.

However, the difficulty then shifts to the identification of highest and

best use. One approach might be to make reference to planning

policy for each plot of land and make a judgement as to whether the land

is developed to its maximum reasonable capacity. However, this would be

open to challenge. It would also be labour intensive and costly.

Nevertheless, it is an approach used in some countries, but normally

where land use is ‘zoned’ for planning purposes. Each land use

zone is delineated and the highest and best use is established for each

zone, within which property of different types would be taxed based on

corresponding tax rates. This approach would need to be designed so as

to acknowledge that not all land within such zones would be permitted to

be developed to the zoned highest and best use by the planning system

e.g. land within the setting of a sensitive heritage asset, or land

which is used as public open space. Therefore, with a zoned

approach, some method is required to allow for adjustment at the

individual parcel level.

This raises another important point. With a zoning system it is

possible to base a land tax on the ‘planned’ use of each piece of land,

the ‘highest and best use’. A discretionary planning system means

that this is not possible since any change of legally permitted use only

occurs once an application to do so has been granted consent. What

this means is that the land value on which a land tax is based may be

assessed with reference to either its highest and best use (zoning

system) or its current use (discretionary system). The modelling

undertaken for this paper is based on the latter – current use.

Land tax is usually assessed as a proportion of market value[1]

of the (un)improved land but can also be based on market rental values.

Rental values relate to market conditions but normally reflect existing

use rather than how the property might be used if sold on the open

market. Basing the tax on capital market value means that valuations

will include ‘hope value’. This is the value that purchasers of

land pay in excess of the value for the permitted use. It reflects

– in financial terms – speculation that there might be a change of

permitted use that would increase the value of the land. Thus, if

a purchaser acquires land at a price that incorporates hope value, he or

she will be exposing themselves to a land tax liability based upon that

value. This point is explained in the quotation below.

‘Agricultural land at a city’s edge is often more valuable for its

development potential than for its agricultural production. If the land

is taxed at its ‘market value’, meaning its value as developable land,

farmers may not be able to continue farming because of high taxes. While

many countries simply exclude agricultural land from the tax base, many

others design a system which taxes agricultural land at its agricultural

value rather than full market value.’ (UN 2011: 43)

Basing land tax on assessments that include hope value could be open to

challenge since its existence and extent are matters of judgement.

It might therefore be preferable to value unimproved land based on a

highest and best use that could reasonably be assumed to be permitted

under existing local planning policy, rather than including a proportion

of value which is assumed to derive from the potential to gain a

planning permission for a different and more valuable use in the future

should planning policy change. If a ‘zoned use’ approach to planning is

taken, this simplifies the issue, but does give rise to the need for

‘parcel adjustments’ for site specific characteristics.

5. PREVIOUS STUDIES OF MOVING FROM A PROPERTY

TAX TO A LAND TAX IN ENGLAND

In 1964 the Rating and Valuation Association reported on a study that

investigated the hypothetical impact of a land tax or ‘site value

rating’ as it was referred to (Rating and Valuation Association, 1964).

This study piloted site value rating in Whitstable, a small town of

approximately 2,000 residents in the county of Kent in south east

England. Annual values of sites were assessed based on full

permissible development value in accordance with the ‘town map’.

All land was valued, including sites of churches and so on, which could

later be exempted as appropriate. The valuations were quite

fine-grained; site-specific aspects such as frontage and proximity to

value-enhancing and value-diminishing characteristics were taken into

account. Capital values were annualised at a rate of 4%. The

result of the study showed that the total value on the existing rating

list (based on occupied taxable units) was £724,100 whereas the site

value list (based on owned land units) was £642,254, of which £14,504

(2%) was from agricultural land.

A follow up study (Land Institute, 1973) used the same approach.

Interestingly, as far as the approach adopted in this paper is

concerned, the study found a ‘remarkable consistency’ between land

values obtained by deducting improvements from total sale price (i.e. a

residual approach), and the few transactions involving bare land that

were available at the time. As with the 1964 study, a relatively

ad hoc decision was made to use a rate of 6% to annualise capital

values. The 1973 study reported an increase in rateable value from

£3,186,543 under the existing rating system to £4,531,093 under a site

value rating system, opposite to the decrease reported in the 1964

study. There may be several reasons for this, but a likely

contender is the rapidly growing value of land over the decade.

Thirty years later McGill and Plimmer (2004) revisited the two

Whitstable pilot studies and, of particular relevance to this paper,

looked in some detail at the predicted winners and losers. Those

who stood to gain were owners of dwellings, retail, commercial and

industrial properties, schools and playing fields, hospitals and homes.

Some of the decreases in assessed value were substantial. Such

reductions can be countered by raising the tax rate but, unless

differential rates are implemented, there would be a significant shift

in relative liabilities. Increases in value related, in the main,

to public uses of land. The exception was agricultural land use, but

this was previously untaxed. What the study seems to show is that

replacing a property tax with a land tax means that, all else equal,

those who previously paid tax based on land and improvements now pay

less since they pay a tax based on land value only. However, the

tax burden may be redistributed so that those in the most valuable

locations pay the most tax, regardless of the value of improvements on

the land.

A great deal has changed since the Whitstable study and, given rising

land values resulting from increased development pressures, particularly

for residential development, it seems appropriate to look afresh at the

implications of a switch from a property tax aimed at occupiers to a

land tax aimed at owners.

6. METHOD

The method adopted for this research is a case study. Reading, a

large town situated 60 kilometres west of London in the south east of

England, was selected as the study location. The area is administered by

Reading Borough Council and has a population of approximately 163,000

residents and an area of just over 40 square kilometres. It comprises

mainly urban land uses but with some rural land uses, and a mix of large

and small owners and occupiers of land and property. Table 3

summarises the Council Tax base for the borough and Table 4 summarises

the Business Rates base.

Table 3: Council Tax in Reading, 2017-18

|

Band

|

Property value

|

Charge

2017/18 |

Number (and %) of dwellings |

Revenue before reliefs |

| A |

up to £40,000 |

1148.89 |

6,450 (9%) |

7,410,341 |

| B |

£40,001 to £52,000 |

1340.36 |

14,010 (20%) |

18,778,444 |

| C |

£52,001 to £68,000 |

1531.85 |

28,670 (41%) |

43,918,140

|

| D |

£68,001 to £88,000 |

1723.33 |

10,860 (15%) |

18,715,364 |

| E |

£88,001 to £120,000 |

2106.30 |

5,430 (8%)

|

11,437,209 |

| F |

£120,001-£160,000 |

2489.25 |

3,270 (5%) |

8,139,848 |

| G |

£160,001-£320,000 |

2872.22 |

1,840 (3%) |

5,284,885 |

| H |

£320,000 and over |

3446.66 |

80 (-) |

275,733 |

| TOTAL |

70,600 |

113,959,964 |

Table 4: Business Rates in Reading, 2017-18[2]

|

Land use

|

Number (and %) of properties

|

Rateable value

(% of total)

|

| Retail and Leisure |

2,158 (40%) |

£116,850,590 (37%) |

| Offices |

1,614 (30%) |

£111,142,825 (35%) |

| Factories and warehouses |

886 (16%) |

£46,842,495 (15%) |

| Other |

790 (15%) |

£38,515,553 (12%) |

| TOTAL |

5,448 |

£313,351,463 |

Council Tax revenue before reliefs was £114m spread over 70,600

dwellings, an average of £1,600 per dwelling. To calculate the

revenue from business rates it is necessary to multiply the rateable

value by the Uniform Business Rate (UBR). Small businesses – those

with a rateable value below £51,000 are assigned a lower UBR. The

total rateable value of these small businesses in the current rating

list for Reading is £55m. With a UBR of 0.466, this produces a

revenue before reliefs of £26m. The total rateable value of

properties with a rateable value of £51,000 or more is £258 million and,

with a UBR of 0.479, the gross revenue is £124 million. This makes

a total Business Rates revenue before reliefs of £150m, an average of

£27,000 per business property.

Net of reliefs, revenue from Council Tax in 2017/18 was £92 million,

equating to £1,300 per dwelling, and from Business Rates it was £124

million[3] equating to £23,000 per property.

The total recurrent land and property tax revenue for Reading in 2017/18

is, therefore, £216 million. To be revenue neutral, a land tax

must yield this amount of revenue.

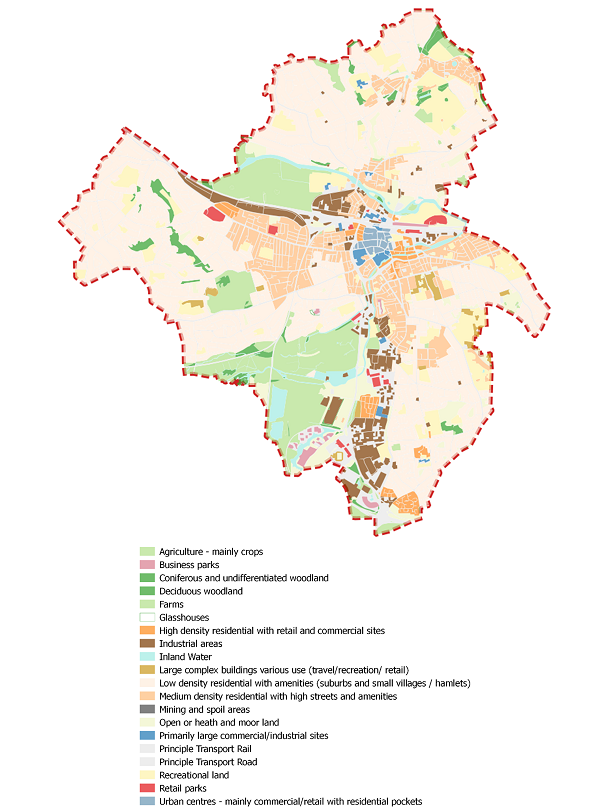

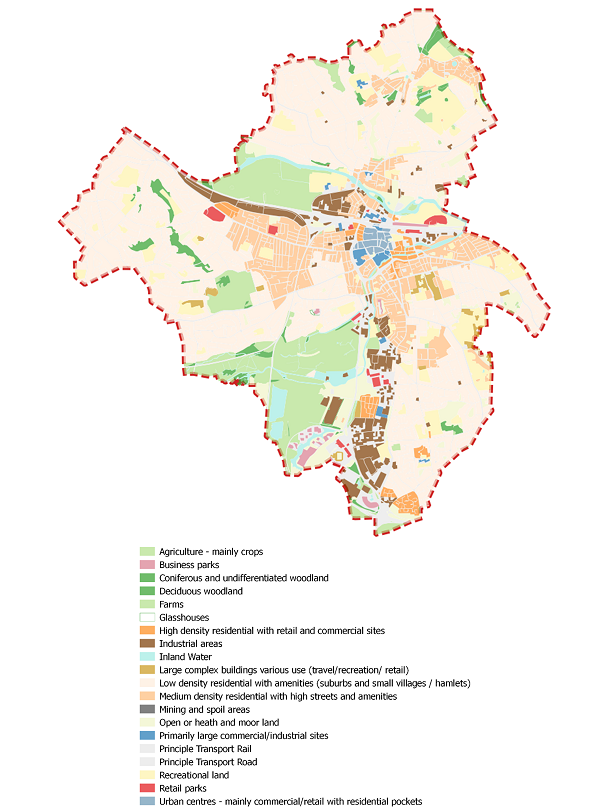

Table 5 categorises land use in Reading and summarises their areas.

Figure 3 shows the 1,339 land use polygons on a map. In practice,

some uses are likely to be exempt from a land tax so only those shaded

will be included in the land tax valuation model.

Table 5: Land use in Reading

| Code |

Land use description

|

Area (m2)

|

| |

Inland water |

1,015,156 |

| |

Open or heath and moorland |

1,868,069 |

| a |

Agriculture - mainly crops |

4,704,744 |

| b |

Glass houses |

5,189 |

| c |

Farms |

19,138 |

| d |

Deciduous woodland |

662,151 |

| e |

Coniferous and undifferentiated woodland |

208,874 |

| |

Principal transport road |

5,382,868 |

| |

Principal transport rail |

342,836 |

| |

Recreational land |

3,322,058 |

| f |

Large complex buildings various use

(travel/recreation/retail) |

346,601 |

| g |

Low density residential with amenities (suburbs and small

villages/hamlets) |

15,421,783 |

| h |

Medium density residential with high streets and amenities |

4,029,255 |

| i |

High density residential with retail and commercial sites |

570,369 |

| j |

Urban centres - mainly commercial/retail with residential

pockets |

188,501 |

| k |

Industrial areas |

1,650,663 |

| l |

Business parks |

187,627 |

| m |

Retail parks |

245,176 |

| n |

Primarily large commercial/industrial sites |

213,022 |

Source: GeoInformation, compiled from Ordnance Survey Open Data and

aerial photos

Figure 3: Land use in Reading

Source: GeoInformation, compiled from Ordnance Survey Open Data and

aerial photos

These land use areas were used to calculate the land tax revenue for

Reading using two valuation models, one acting as a cross-check on the

other. The first model was based on comparison with published land

value data and the second was a residual valuation model in which

estimated build costs are deducted from property values to arrive at

land values. Separate valuation models were constructed for the

non-domestic and domestic land uses listed in table 6.

Table 6: Land uses

|

|

Land Use

|

Land use code from

Table 4

|

|

| |

Agriculture |

a, b, c, d, e |

|

| |

Retail and leisure |

f, j/2, m |

|

| |

Office |

j/2, l, n/2 |

|

| |

Industrial and storage |

k, n/2 |

|

| |

Detached houses |

g |

|

| |

Semi-detached houses |

g |

|

| |

Terraced houses |

h |

|

| |

Apartments |

i |

|

The residual valuations were based on the land use specific

assumptions set out in table 7. The values of residential units

were based on transaction prices obtained from the Office for National

Statistics[4]. Rental values and investment

yields for retail, office and industrial space were obtained from CoStar[5].

Agricultural land values were not modelled, they were the same as the

comparison approach.

Build cost estimates[6] were obtained from the

Building Cost Information Service[7] of the Royal

Institution of Chartered Surveyors. Planning costs are assumed to

cover any planning obligations and community infrastructure levy that

may be required. Building sizes were obtained from CABE (2010) and

DLCG (2016). Development density or floorspace-to-land ratio is a

difficult metric to find evidence for. In 2017 the Government’s

Land Use Change Statistics recorded a density of 32 addresses per

hectare on for new developments, but higher at 40 addresses on

previously developed or brownfield land and lower at 26 addresses on

non-previously developed or greenfield land (MHCLG, 2018b).

Assuming an average dwelling size of 90m2 that equates to 4,000m2 of

residential floorspace per hectare, i.e. 40% density. Indicative

density for Reading town centre is 100 dwellings per hectare (dph) or

higher, for urban areas it is 60-120 dph and for suburban it is 30-60

dph[8]. The densities for town and city

centres – where apartments are assumed to be the predominant form for

residential development – is in line with the assumption made in DCLG

(2015)[9]. Densities for commercial land uses

are very difficult to find evidence for. Town centres may be close

to 100% site coverage, more for office space.

Table 7: Residual valuation assumptions

| |

Apart-

ments

|

Terraced houses

|

Semi-detached houses

|

Detached houses

|

Office (centre)

|

Office (out of town)

|

Industrial & storage

|

|

Values (£/m2)

|

£4,035 |

£4,456 |

£4,029

|

£4,796 |

£4,508 |

£3,607 |

£1,818 |

| Build cost (£/m2) |

£1,599 |

£1,332 |

£1,309 |

£1,534 |

£1,905 |

£1,500 |

£1,119 |

External works

(% build cost) |

15% |

15% |

15% |

15% |

10% |

10% |

10% |

Planning costs

(% value) |

15% |

15% |

15% |

15% |

5% |

5%

|

0% |

| Net:gross floor area ratio |

- |

- |

- |

- |

80% |

80% |

100% |

| Building size |

61 m2

(2-bed flat) |

71 m2

(2-bed house) |

96 m2

(3-bed house) |

121 m2

(4-bed house) |

- |

- |

- |

| Floorspace:plot size ratio[10] |

200% |

50% |

40% |

30% |

300% |

200% |

100% |

| Building period |

2 years |

2 years |

2 years |

2 years |

1.5 years |

1.5 years |

1 year |

In addition to the land use specific assumptions itemised in table 6,

the following generic assumptions were also made:

- Finance at 6% per annum on half build costs and fees over the

building period

- Land acquisition costs (Stamp Duty Land Tax plus legal and

agent’s fees) at 6.5% of land price

- Developer’s return at 20% of development value

- Fees for construction professionals at 12.5% of build costs

- Marketing and sale costs at 2% development value

The residual valuation model, and its application to each of the land

uses, is shown in the appendix. The gross development values of

the commercial and industrial land are very sensitive to the choice of

yields

7. RESULTS

Turning to the comparison valuation model first, this had to be

undertaken at a highly aggregated level due to the limited availability

of sub-regional land value data. The most up to date source of

land value data is the UK Government’s Ministry for Housing, Communities

and Local Government (MHCLG, 2018a). In 2015 land values were £4.9

million per hectare for residential development land in the Reading

local authority area and £2.0 million per hectare for industrial land.

Agricultural land value in the surrounding area of the Thames Valley and

Berkshire was estimated to be £22,500 per hectare. Office land

values for Reading were reported at £21.7 million per hectare for

commercial land on the edge of the town centre and £8.67 million per

hectare for commercial land on the edge of town or on business parks.

No land values were published for retail or leisure land uses so these

land uses were assumed to be valued at the same level as commercial

land.

The land values were used to calculate land tax revenue using the

comparison model. In order to generate the same level of

pre-relief tax revenue as the current property taxes, the tax rate would

need to be 1.90%. The resultant breakdown of values by land use is

shown in Table 8. Areas were estimated from the land use areas in

Table 5.

Table 8: Land tax results from the comparison model

|

Land Use |

Area (m2) |

Land value

(£/ha) |

Land Value (£) |

Tax revenue

(at a rate of

1.90%) |

Tax (£/m2)

|

| Commercial (city centre) |

188,501 |

21,700,000 |

409,047,717 |

7,771,907 |

41.23 |

| Commercial (out of town) |

885,915 |

8,670,000 |

768,088,627 |

14,593,684 |

16.473 |

| Residential |

20,021,408 |

4,900,000

|

9,810,489,806 |

186,399,306 |

9.31 |

| Industrial |

1,757,174 |

2,000,000 |

351,434,720 |

6,677,260 |

3.80 |

| Agriculture |

5,600,067 |

22,500 |

12,600,150 |

239,403 |

0.04 |

| TOTAL |

28,453,065 |

|

11,351,661,020 |

215,681,559 |

|

The comparison valuation model is broad-brush and based on limited

data relating to land values. The residual method offers a more ‘first

principles’ approach. It also provides an opportunity to

categorise residential land use into three distinct densities.

Table 9 shows the resultant land values from the residual model for each

land use together with the tax revenue. The land values are lower.

This is because the Government’s estimates of land value assume a

standard development with no abnormal costs and no planning obligations

or infrastructure levy. With the residual land values, a tax rate

of 3.00% is required to approximately match the revenue from the current

property taxes.

Table 9: Land tax results from the residual model

|

Land use

|

Area (m2) |

Land value (£/ha)

|

Land value (£)

|

Tax revenue

at a rate of

3.00%

|

Tax (£/m2)

|

| Commercial (city centre) |

188,501 |

22,315,579 |

420,651,465 |

12,619,544 |

66.95 |

| Commercial (out of town) |

885,915 |

11,902,038 |

1,054,419,865 |

31,632,596 |

35.71 |

| Residential (low density) |

15,421,783 |

2,441,527 |

3,765,269,469 |

112,958,084 |

7.32 |

| Residential (medium density) |

4,029,255 |

3,349,019 |

1,349,405,153 |

40,482,155 |

10.05 |

| Residential (high density) |

570,369 |

9,269,725 |

528,716,808 |

15,861,504 |

27.81 |

| Industrial |

1,757,174 |

125,137 |

21,988,727 |

659,662 |

0.38 |

| Agriculture |

5,600,067 |

22,500 |

12,600,150 |

378,004 |

0.07 |

| TOTAL |

28,453,065 |

|

7,153,051,636 |

214,591,549 |

|

The proportion of total tax revenue that is generated by agricultural

land is very small, although it should be noted that the amount of

agricultural land in the Reading borough is very low. By far the

largest proportion of tax revenue is generated from low density

residential and this is likely to be the case for many parts of England,

particularly in the south east, because of the combination of high land

values and low density (land extensive) development.

So the taxable land in Reading is valued at a total of £7.1 billion

and this generates a tax revenue of approximately £215 million assuming

a tax rate of 3%, close to the £216 million generated from current

Council Tax and Business Rates. However, the rate is not the

crucial issue here. What is particularly noteworthy is the shift

of tax liability from businesses to residents. In 2017 businesses

generated 57% of revenue from recurrent property taxes in Reading (the

same proportion as for England as a whole) and residents generated the

remaining 43%. The land tax shifts the burden substantially from

business (21%) to residents (79%).

This may be an outcome of different tax rates that are currently

applied to domestic and non-domestic properties. As a proportion

of capital value, the tax rate on non-domestic properties is higher than

for domestic properties. In December 2017 the average house price in

Reading was £311,823 and the average Council Tax Bill was £1,365 or 0.4%

of capital value. For non-domestic property the uniform business

rate was 47.9% in 2017/18 and, if we assume a capitalisation rate of 6%,

this is an effective tax rate on capital value of 2.9%. If a

common tax rate is applied, then there will be a substantial

redistribution of the tax burden from non-domestic to domestic

properties. The expectation is that the redistribution would be

less marked for dwellings in high Council Tax bands, but this depends on

the relative sizes of land parcels across the Council Tax value bands;

low value dwellings with large plots may see a large redistribution.

In order to look further at the revenue implications of switching

from an occupier tax to ownership tax, it is useful to examine the size

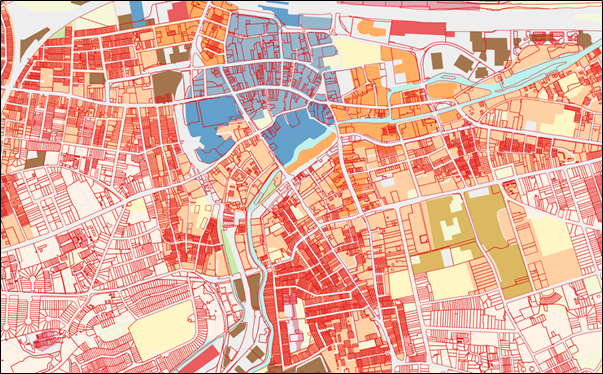

and composition of the tax base. To begin, it is possible to tally

the number of taxpayers in Reading under the current property tax system

and compare that with the number of ownership parcels. Freehold

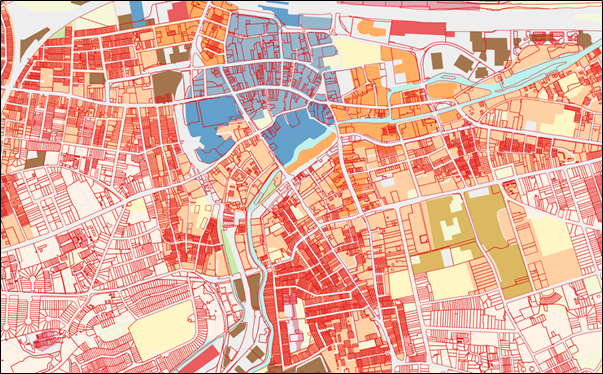

parcel extents are published by the Land Registry and these are

illustrated in red outline for the centre of Reading in figure 4,

overlaying the land use map (from figure 2). In total there are

55,014 freehold parcels covering the whole of the Reading borough,

although there are a few gaps where land has not been registered yet.

This contrasts with the 70,600 dwellings that are liable for Council tax

and 5,448 properties liable for Business rates. This is a total of

76,048 taxable entities. Therefore, a switch to a land tax on

owners would see a reduction in the size of the tax base of 21,034 tax

payers (28%).

Figure 4: Freehold parcel extents (red outlines) for central Reading,

overlaying the land use map

Source: The HM Land Registry INSPIRE Index Polygons dataset is subject

to Crown copyright and is reproduced with the permission of HM Land

Registry

(© Crown copyright and database rights 2018 Ordnance Survey 100026316)

The next step is to take a more detailed look at land uses of the

freehold parcels, both in terms of number of parcels and land area.

This requires a spatial overlay using a GIS to allocate each freehold

parcel to a land use. For most parcels this is straightforward as

they can be entirely allocated to the relevant land use. A small

number, though, straddle more than one land use. In these cases,

the freehold parcel was duplicated and allocated to each land use that

it straddled. This explains why the total number of freeholds in

table 10 is slightly greater than the original 55,014.

Table 10: Taxation of freeholds in Reading

|

Land use

|

Area (m2)

|

Number of

freeholds

|

Area perfreehold

(m2) |

Tax (£/ha) |

Tax per

freehold

|

| Commercial (city centre) |

188,501 |

364 |

518 |

66.95 |

34,669 |

| Commercial (out of town) |

885,915 |

332

|

2,668 |

35.71 |

95,279 |

| Residential (low density) |

15,421,783 |

36,583 |

422 |

7.32 |

3,088 |

| Residential (medium density) |

4,029,255 |

16,056 |

251 |

10.05 |

2,521 |

| Residential (high density) |

570,369 |

1,235 |

462 |

27.81 |

12,843 |

| Industrial |

1,757,174 |

1,193 |

1,473 |

0.38 |

553 |

| Agriculture |

5,600,067 |

1,181 |

4,742 |

0.07 |

320 |

| TOTAL |

28,453,065 |

56,944 |

|

|

|

Looking at the switch from the current property tax to a land tax,

compared to 5,448 business rates properties, there are 1,877 freeholds

classified as commercial and industrial. Compared to 70,600

Council Tax dwellings, there are 53,874 freeholds classified as

residential land use. The 1,181 freeholds classified as

agricultural would be new to the tax base. The average area per

freehold is also shown in the table, and this allows calculation of the

average tax liability per entity. The tax per agricultural land

owner is very low due to their small size (a little under half of one

hectare on average). This reflects the composition of agricultural

land ownership in the Reading borough which contains mainly small land

holdings, which tend to be more valuable per unit area than large farms.

For city centre and out of town commercial land the tax liability per

freehold is much higher (£35,000 and £95,000 respectively, compared to

£23,000 per property under Business Rates in 2017). Many of these

freeholds, and particularly those located out of town, will comprise

multiple occupiers in office buildings, shopping centres, retail and

business parks. The major shift is for residential dwellings; the

average Council Tax bill was £1,300 per dwelling in 2017 but under the

modelled land tax this would increase to £3,000 for low density, £2,500

for medium density and £13,000 for high density residential freeholds.

The high-density amount is much higher because each freeholder is likely

to have multiple residential occupiers and the tax liability is likely

to be shared among those occupants.

8. CONCLUSIONS

The two research questions were: how might the valuation of

unimproved land be undertaken in a developed economy where most

transactional evidence relates to improved land and what are the revenue

implications of switching from an occupier tax to ownership tax?

The lack of transactional evidence for unimproved land sales is a

significant concern for land tax administration. What little

evidence there is often requires adjustment to account for differences

between parcels, not least as a result of locational differences that

can have a substantial influence on value. Land prices may also

reflect alternative use value and development (hope) value and, if a

land tax is based on such prices, owners may have difficulty in paying

tax if they are using the land for a lower value use. For example,

the owner of an organic farm may be required to pay a tax based on land

value that assumes the farm is used for intensive farming. Would

government wish to penalise land owners who choose not to maximise

economic value? Instead, a residual valuation model values land in

its existing use and resorts to more fundamental evidence of build costs

and property values to derive land value.

Switching from a property tax to a land tax is likely to create

winners and losers, yet the scale of the shift from businesses to

residents is considerable; from entities that don’t vote to those that

do, and this perhaps explains why it has never been done. Of

course, the use of different tax rates can alleviate the shift and land

owners would probably attempt to pass on the tax burden to occupiers in

the form of rent or service charge, but this would only be possible

where the market allows. Turning finally to agricultural land,

expansion of the tax base to include this land uses has a marginal

impact in Reading but is likely to be more contributory where such land

is more dominant in relation to urban land uses.

It is important to recognise that detailed and up to date land

ownership records are essential, as is the existence of comprehensive

land use planning and development control system. After all, land

use allocation is a key value influence, and land values are very

sensitive to planning assumptions. Further research will examine a

more rural case study area to investigate in more detail the

implications of including agricultural land in the tax base. Areas

of investigation are likely to include the requirements for a complete

and up to date register of land ownership, establishing highest and best

use and separating land value from land and property value.

REFERENCES

CABE (2010) Dwelling Size Survey, report by Scott Wilson for CABE,

Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment, April 2010.

Connellan, O. (2004) Land value taxation in Britain: experience and

opportunities. Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. Cambridge,

Massachusetts.

Corlett, A., Dixon, A., Humphrey, D. and von Thun, M. (2018)

Replacing Business Rates: taxing land, not investment.

Corlett, A. and Gardiner, L. (2018) Home affairs: options for

reforming property taxation. Intergenerational Commission Report.

Resolution Foundation. March 2018.

DCLG Land Use Statistics (Generalised Land Use Database) 2005 for

Reading. Department for Communities and Local Government.

DCLG (2016) English Housing Survey: Housing Stock Report, 2014-15.

Department for Communities and Local Government. July 2016

Dunne, T. (2005) Land value taxation: persuasive theory but

practically difficult. Dublin Institute of Technology. Property

Valuer, IAVI, Dublin, Ireland. Spring 2005.

Dye, R. and England, R. (2010) Assessing the theory and practice of

land value taxation. Policy Focus Report. Lincoln Institute of Land

Policy. Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Gibb, K. and Christie, L. (2015) International literature review for

the Commission on Local Tax Reform. In The Commission on Local Tax

Reform: Volume 3 – Compendium of Evidence. pp. 126-164.

George, H. (2005) Progress and Poverty. Cosimo Classics.

New York. (Originally published in 1879 by E. P. Dutton and

Company.)

Hills, J. and Sutherland, H. (1991) The Proposed Council Tax, Fiscal

Studies, Vol 12, No 4, 1-21.

IPPR (2005) Time for land value tax? D. Maxwell and A. Vigor (eds.)

Institute for Public Policy Research and the Department of Politics and

International Relations at the University of Oxford.

Land Institute (1973) Site Value Rating: Report on a Research Carried

Out in the Town of Whitstable, January 1974

Leishman, C., Bramley, G., Stephens, M., Watkins, C. and Young, G.

(2004) After the Council Tax: impacts of property tax reform on people,

places and house prices. Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Lichfield, N. and Connellan, O. (1997) Land value taxation in Britain

for the benefit of the community: history, achievements and prospects.

Lincoln Institute of Land Policy Working Paper. WP98NL1.

Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

Lyons, R. (2011) Residential site value tax in Ireland: an analysis

of valuation, implementation and fiscal outcomes. Smart Taxes

Network.

Lyons, R. and Wightman, A. (2013) A land value tax for Northern

Ireland. Research Report: seven. Centre for Economic Empowerment.

MHCLG (2018a) Land value estimates for policy appraisal: May 2017

values. Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government. May 2018.

MHCLG (2018b) Land Use Change Statistics in England: 2016-17,

Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government. Planning:

Statistical Release. 31 May 2018.

McGill, G. and Plimmer, F. (2004) An Examination in to the Effects of

Land Value Taxation in the UK: An Update of the Whitstable Case Studies,

Lincoln Institute of Land Policy Working Paper, WP04GM1.

Mirlees, J., Adam, S., Besley, T., Blundell, R., Bond, S., Chote, R.,

Gammie, M., Johnson, P., Myles, G. and Poterba, J. (2011) Tax by Design:

The Final Report of the Mirlees Review. Institute for Fiscal Studies.

Norregaard, J. (2013) Taxing immoveable property: revenue potential

and implementation challenges. International Monetary Fund. IMF

Working Paper. WP/13/129.

Rating and Valuation Association (1964) Rating of Site Values: Report on

a Pilot Survey at Whitstable.

de Soto, H. (2000) The mystery of capital: why capitalism triumphs in

the west and fails everywhere else. Black Swan, London.

UN (2011) Land and property tax: a policy guide. United Nations

Habitat and the Global Land Tool Network.

Wightman, A. (2013a) A land value tax in England: fair, efficient,

sustainable.

Wightman, A. (2013b) A land value tax for Scotland: fair, efficient,

sustainable.

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Peter Wyatt is a Chartered Valuation Surveyor who has conducted

extensive teaching, consultancy and research in land management and

valuation. Currently Professor of Real Estate Appraisal in the

School of Real Estate & Planning at the University of Reading, he has

developed and delivered national and international university programmes

at all levels, has published widely in leading real estate journals and

has published two text books. Professor Wyatt has been involved

with and lead national, European and international real estate research

projects. Professor Wyatt is lead author for a set of voluntary

guidelines on the valuation of tenure rights, published by the UN FAO.

Recent work with UK Government and professional investigated the theory

and practice of development viability appraisal in planning policy,

focusing specifically on land value capture.

CONTACTS

Professor Peter Wyatt MRICS

Professor of Real Estate Appraisal

Department of Real Estate & Planning

Henley Business School

University of Reading

RG6 6AW

UK

Tel. +118 328 6337

Email: p.wyatt[at]reading.ac.uk

[1] There are other bases of assessment: soil

quality for agricultural land; and replacement cost valuations for

buildings, but these are usually employed when market transaction

evidence is not available.

[2] The Rating List downloaded from the

Valuation Office Agency’s website (voa.gov.uk) on the 15th July 2017

included 5,462 properties with a total rateable value of £313m, an

average of £57,000 per property. Some of these properties were

temporary structures which, although in the Rating List, are not

assessed for rating purposes.

[3] Source: GOV.UK, live tables on local

government finance, last updated 27 June 2018).

[4] House Price Statistics for Small Areas

(HPSSAs). HPSSA Dataset 12. Mean price paid for administrative

geographies.

[5]

www.costar.co.uk

[6] Mean average costs (including preliminary

costs) per square metre of gross internal area of new space in Reading

for the fourth quarter of 2017.

[7]

http://www.bcis.co.uk/

[8] Draft Reading Borough Plan, May 2017, p66,

Reading Borough Council

[9] In that report it was assumed that a

hypothetical scheme for a one-hectare (10,000m2) site would be a

multi-storey development of 269 units comprising one, two, three and

four bed flats with a gross building area of 23,202m2 and a net sales

area of 19,722m2.

[10] This density assumption has a significant

impact on the residual land value.