Article of the Month -

May 2012

|

MERCATOR

Jan de Graeve (Belgium), Director of the FIG IIHSM

1) The paper is written by Jan de

Graeve, FIG International Institution for the History of Surveying and

Measurement and honorary member of FIG, to celebrate the 500 anniversary

of Gerand Mercator. Furthermore it will be presented at the FIG Working

Week, History Workshop in Rome, Italy May 2012. The paper is a short

introduction to the life and work of Gerand Mercator to highlight the

exceptional place he has in the history of the surveying profession.

Keywords: Mercator, Quincentenary, Atlas, Projection.

SUMMARY

2012 is the quincentenary of the birth of Gerard Mercator. Although

best known for the map projection named after him he was also known for

the Mercator Atlas, indeed even the introduction of the word "Atlas" and

for his work in cartography but maybe not so much for his basic work as

a land surveyor. This paper is a short introduction to his life and work

to highlight the exceptional place he has in the history of our

profession.

Figure 1. Gerhard Mercator

INTRODUCTION

Gerard Mercator's name rings a bell, as a cartographer, the Mercator

atlases, the Mercator projection, construction of mathematical

instruments and globes, but primarily he made his living as a land

surveyor. He was born in Rupelmonde, in Flanders, on March 5th 1512, 500

years ago, from parents who sold and repaired shoes on market places.

His original name was Gerard de Cremer (a market merchant) and his name

was latinised during his studies at Louvain. The University was

chartered in 1525 and basic studies were the trivium and for those

studying sciences the quadrivium of arithmetic, geometry, astronomy and

music.

During his studies, he met Gemma Frisius who introduced him to

astronomy. As he had difficulties understanding the complexity he

started reading geometry, using an Euclid edition by Vogeler, published

in l529 in Strasburg: Elementale Geometricum ex Euclide Geometra, a

Jerome Voegeler as a start. To get an advanced knowledge, he went on to

read Oronce Fince's: Liber de Geometra Practica, 1544, either the Latin

or French version. This we read in a letter he sent to Mr Haller in

1581, to whom he explained how he improved his knowledge of geometry. In

the same letter he explained how he read about border disputes, in some

book, but could not remember the name of the author. I found out that it

must have been the Galland first edition of 1544: De Agrarum

dimentionibus.

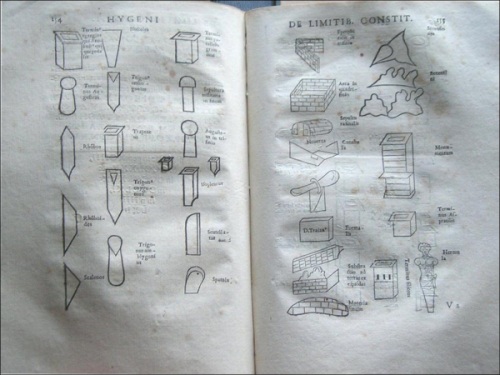

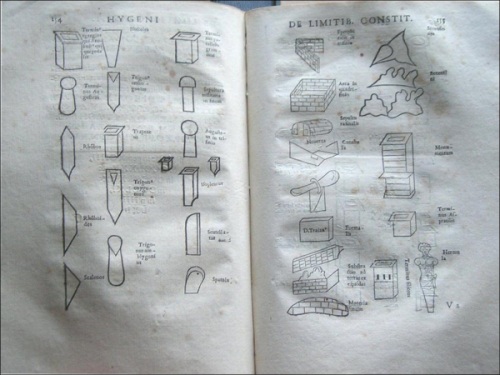

This convolute of Latin texts from the Roman authors explains that in

Roman times the lands were allotted to the veterans once they became 40

years old and received their salary for a long life serving the army.

This book deals not only with the mathematics of land division and

border limits but explains the law systems and legislation that has

governed most land divisions in the Roman empire, not only in Italy but

also in North Africa, Spain and other Roman territories.

The surveyors used a "secret language", a kind of coordinates in

length to find distances between the border stones. This system could

still be of some inspiration for our colleagues today. As a Land

Surveyor Gerard Mercator had practised measuring land and solving border

disputes, well before starting his career as a cartographer.

Figure 2. Galland: Borderstones of Roman times

From Gemma Frisius he read: De locorum describendum ratione,

published for the first time in 1533, as an annex to Petrus Apianus:

Comographia by Bonte in Antwerp. The principal was simple. In a triangle

there are 3 angles and 3 distances. If you know 1 distance and 2 other

data, you can solve the triangle, and find (or calculate) the other

elements. It was written in Diets or Flemish. The instruments were very

much like the back of an astrolabe, used in a horizontal manner.

His first important map, presented to the Emperor Charles V by the

city of Ghent in 1540, was called: The Flanders Map. It was a fairly

precise map using the intersection method explained above. He was

commissioned to produce this beautifully engraved map by Granville, but

he did not do the field work; Dr Eric Leenders and I found evidence that

Jacob van Deventer did the fieldwork. Jacob van Deventer measured all

countries belonging to the emperor Charles V. (1500 - 1557).

The cities from where the other villages were intersected were marked

by a double concentric circle. Curiously no historian or cartographer

had understood the significance of this double circle. The larger cities

are engraved and marked with a large church symbol, the smaller with a

small chapel. Of this the centre was each time marked with a single

circle.

Only Gerard Mercator used this system and it is only very recently

that this system was unveiled to the world of the cartographer. This is

despite the fact that the original text on the map of Ghelderland (in

the Netherlands) clearly explains it "in Dutch". Unfortunately not so

many scholars read the inscription on the maps, which are often written

in Latin or in the vulgar languages from 16-l7th centuries and are more

difficult to read or rather "decipher", or are printed in Gothic.

This major achievement in a short time ( a half year for the

engraving) could only have been realised by a close collaboration

between the land surveyor measuring from church towers and forming the

triangles into a small network. The engraver was G. Mercator.

The instrument for measuring the angles had a compass built into the

full circle and the instrument could be oriented to the North (magnetic

north). The deviation of the compass was only discovered later although

Mercator made a substantial contribution to describing the deviation of

the magnet and finding out that the magnetic Pole was not situated on

the Earth's North - South axis through the Poles. He described that in

his correspondence with John Dee, from Cambridge.

In 1546 Gerard Mercator wrote a long letter to André Perrenot de

Granville on February 23 rd. where he explained that the magnetic North

did not correspond with the geographic North. The implications were the

need for map projections. He was apparently one of the very first to

describe the magnetic deviation.

In 1544 G. Mercator was suspected by the "Holy Inquisition" of heresy

and put in jail for 6 months in the fort of Rupelmonde. In fact, he was

solving a property dispute in what is today Zeeland, between the

villages of Axel and Hulst, where 2 religious communities of Ghent, the

Abbey of St-Pieters and the Abbey of St-Baafs, both claimed the same

land to be their property.

At the same time Gerard Mercator stayed in Rupelmonde to solve some

inheritance problem as well, from a deceased uncle of his. As he was

absent from Leuven, where he normally lived with his family (Barbara

Schellekens and children Romuald, Bartholomeus, Arnold and Emily), the

sheriff was looking for him as he was on a list of' possible heretics,

some of which had been executed.

In the l6th century, the propagation of protestantism was firmly opposed

by the Roman Catholic Church, and the books by Calvin, Luther, Zwingler

and others were not allowed by law and prohibited, the sanction: the

death penalty.

This is probably one of the reasons why Gerard Mercator moved in

March 1552 to Duisburg, in Germany on the Rhine. One of his great

patrons, the Emperor Charles V had abdicated in 1550 and moved to Juste

in Spain. The prospects to see a university created in Duisburg was

another reason to go and live in a more tolerant religious environment.

Gerard Mercator measured a large part of Lotharingen (in the French

region of Lorraine) and during the time spent there he injured himself

seriously, he fell ill and never returned to land surveying leaving this

activity to his son Romauld who measured the city of Duisburg and Arnold

Mercator received a privilege from Maximilian II for a map of Koln in

1571.

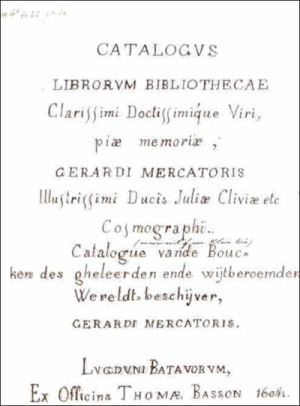

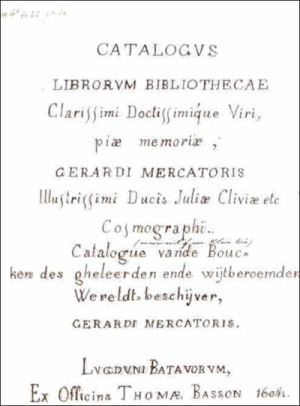

Gerard Mercator did read a lot of books, and his library was sold in

1604 l0 years after he had passed away. A public auction of the Mercator

library was organised in Leyden (Netherlands), an impressive 1000 books,

in 900 volumes, were sold: there were also religious books: 50% catholic

books and 50% others, historic works, scientific books and others.

Figure 3. Auction catalogue transcription

A large portion of the history books involved what we would call

geography. There were about 200 books on mathematics and also Libri

Politores, which we could call "rare books". Most books in l6th century

were written in Latin, the universal language, but also in "Gallici",

books in Italian, Spanish and French, and Teutonici: English and or

Flemish (Diets) and German.

In the 19th century, there was controversy between scholars about

Gerard Mercator; was he German?, was he Flemish?, born in 15l2 in

Flanders, he went to Duisburg in 1552 and died there in 1594, so 40

years in Flanders and 42 in Germany. He signed always: Gerardus Mercator

Rupelmondanus or GMR, as, for example, on the border of an Astrolabe. In

fact he was a real European writing and reading in Latin, the learned

language, Flemish or Diets, French, English, German, Spanish, Italian

but no Greek. The books in his library were printed in many languages

and we found his correspondence also in all of the above languages.

Although Gerard Mercator did not travel very much even for a l6th

century learned person, from his correspondence we understand that he

had a fairly good knowledge about the latest discoveries not only in the

New World but also in Central and East Asia.

One of his most important contributions for the time was his

Chronology which he produced in folio in I567, first edition. From his

readings he chronologically wrote down all the important events known in

history books not only the dates of coronations or deaths of kings,

battle fields or peace treatises, but also natural phenomena, earth

quakes, volcanic eruptions, appearances of Stella Nova, sun - and moon

eclipses noted in history books and he recalculated them all in the

different calendar systems: by the Jewish - Greek Olympiades - in Roman

calendar from Romulus and Remus and by the Mohammedan and Christian

calendars. A second edition appeared in 4º in 1575.

His chronology, and his publication of the revised Ptolomeus Atlas,

as part of his Opus Magnus including geography and cosmology, was

unfortunately not finalised before 1594.

THE MERCATOR PROJECTION

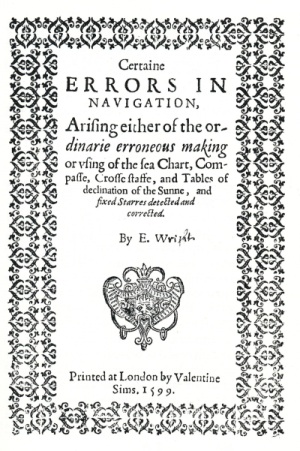

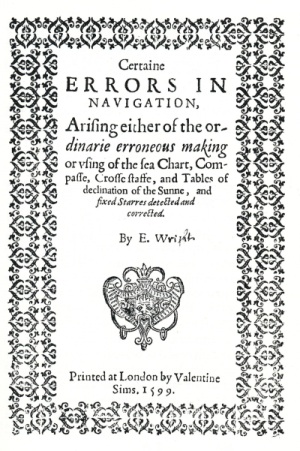

We cannot ignore the Mercator projection as it is still in use today

particularly in navigational maps for aviation. In navigation a major

problem was to draw on a flat map a large region which is on a spherical

globe. One has to explain in two dimensions a three dimensional reality.

If on a ship you want to go from A to B, you can calculate the angle

that your ship will cross the meridians passing through both poles. The

line which joined the points crossing all the meridians with a similar

angle, is called a loxodrome, which is a complex curved line ending up

near the pole, but is intricate to calculate.

Mercator tried to understand and solve the problem by turning the

complex loxodrome into a straight line and changing the meridians into

parallel lines, distorting the areas near the poles. To compensate he

invented the system of increasing latitudes. He applied his system in a

famous world map Ad usum navigatium, 1569, but it took a long time

before the system was mathematically explained and proved by William

Wright in Certain errors in Navigation, published in 1599 and 1657.

Figure 4. Edward Wright: Certain Errors of navigation

THE MERCATOR ATLAS

Before 1595 there had been individual map productions and also

volumes published with many different maps. The candidate buyer chose

the maps he needed and had them bound together. So, if you wanted to go

from Central Europe to Jerusalem, you do not need the maps of Spain, nor

Portugal, nor France nor parts of Africa.

For travelling to the Americas those maps were essential even if they

were imperfect but the rest of the world was then not needed. If you

want to go from Rome to Antwerp or Amsterdam, you need the maps of

Italy, Switzerland, Germany and the l7 provinces. The maps were bound

together on demand. Mercator issued the full set of maps. His first

atlas, published posthumously in 1595, by his son one year after he

died, was given the name "Atlas", which has been in use even since.

On the occasion of the 500th anniversary, a facsimile has been issued by

Mercatorfonds in folio edition, and a Verlag produces a large reprint in

full size in colour. The learned introduction to both is written by Dr

Thomas Horst from Munchen originally in German, but translated into

English, French and Flemish (Dutch).

Mercator died in December 1594 in Duisburg, at the advanced age of

82. He is remembered for the Atlas, and his projection with increasing

latitudes. As a perfectionist, he always wanted the ultimate precision

which he learned in his earlier career as a land surveyor.

He will be remembered as a Great European Land Surveyor and

Cartographer.

Coming Events

To commemorate GERARD MERCATOR. many events are planned and prepared

- In Rupelmonde, their Highnesses Prince and Princess PHILIP of

Belgium have unveiled a sculpture of the young Mercator, to inspire

the future generation that every one can become an important person.

- In St-Niklaas: an exhibition in the local Museum STEM; the at

the library of Gerard Mercator on the other side of the park is an

exhibit "Mercator Digitalised" together with an exposition of 4l

mathematical books from the Gerard Mercator library by Jan De

Graeve. This runs until 1st July 2012.

- An international colloquium from 24 to 27 April 2012, in

St-Niklaas and also

in Antwerp: Plantin Moretus Museum: "Mercator and travelling in l6th

century"

- In Dortmund: A major exhibition in the city museum: "Mercator,

surveyor and

Cartographer" (600 m2)

Jan De Graeve published The Mercator Scientific Library, in "Le Livre

et L'Estampe" 202 pages + illustrations

References

- Le Livre et L'Estempe, journal of the Belgian Bibliophile

society of Aril. 2012. A 202 page paper by Jan de Graeve on the

scientific library of Gerard Mercator.

- The photographs are from a presentation made about the books in

the Author's library.

Biographical notes

Jan de Graeve is Director of the International Institute for the

Hstory of Surveying and Measurement. (IIHSM). He is an Honorary member

of FIG.

Contact

Prof. Jan de Graeve,

Director IIHSM,

1020 Brussels,

5 Ave de Meysse,

Belgium.

Tel. 0032 (0)2 268 1025

Fax: 0032 (0)2 262 1033

|