Article of the Month -

April 2018

|

A consideration for a conceptual

partnership framework in building spatial data infrastructures in

developing countries

|

|

| Lopang MAPHALE

|

Kealeboga Kaizer

MORERI |

This article is accepted as peer review

paper and will be presented at the congress 2018 in Istanbul, Turkey.

SUMMARY

This is a brief statement of the paper on Spatial Data

Infrastructures (SDI) and partnerships in the context of developing

countries. The concept of SDI started developing in the 1990s. Its real

explosion was felt after the 1993 presidential order 12906 by the then

United States of America President Clinton. It was held then that this

concept was going to spread and grow across the countries of the world

as it embraces geospatial information sharing across multiple

organizations. In terms of word, the concept did spread but in terms of

implementation coupled with growth it did not progress as anticipated

particularly in developing countries. They have struggled with the

implementation of this concept with African countries at the fore

front. To understand the challenges faced by developing countries, this

paper focuses on the aspect of partnerships. Partnerships are important

aspects which SDI foundations should be built upon. This paper explores

the SDI concept through its components and links it with the aspect of

partnerships. In so doing an SDI Partnership framework is advanced

which can be used by developing countries especially in Africa to pursue

their SDI developments. This framework is premised on the aspect of

institutional arrangements in respect to underlying behaviour, technical

and information policy issues. The framework is envisaged to guide SDI

adaptability analysis, modelling and design to meet a developing

country’s spatial data systems implementations. The usefulness and

significance of the framework was tested by interfacing it with existing

SDI assessments of African countries to prove that the proposed

partnership framework can be useful to their development and growth.

1. INTRODUCTION

A Spatial Data Infrastructure (SDI) is a conglomerate of geospatial

technologies and institutions fused with multi-sectoral professional

activity. If properly implemented and structured, it can play a leading

role in supporting major government, business and private

decision-making avenues This conglomeration of institutions together

with various professions need to be kickstarted and founded on good

working relations, which this paper refers to as partnerships. In the

last 30 years the need for partnerships in geospatial data collection,

processing and dissemination have been exposed by weaknesses such as

duplication of effort, wastage of resources and a lack of policies and

standards that enable functional partnerships to succeed. To address

these challenges, politicians like the USA President in 1994 through an

executive order 12906 and professionals like John McLaughlin in 1991

(GeoConnections, 2013) started looking at geospatial data as a resource

that can be developed into an infrastructure to benefit all stakeholders

and communities at large. This view has been emphasised by Crompvoets et

al. (2008), who stressed that spatial information should be treated as a

multi-stakeholder commodity meant to mutually benefit all those

involved.

Activities which promote partnerships in the development of SDIs are

its capabilities in spatial data sharing and exchange with the help of

Information and Communication Technologies (ICT). For data sharing

and exchange to happen effectively, sufficient collaborations and

coordination need to be established. Partnerships in the

development of SDIs can be controlled by an anchor structure such as an

SDI committee or coordinating organisation. Examples of such structures

are the USA Federal Geographic Data Committee (Williamson, Rajabifard, &

Enemark, 2003) and the European INSPIRE (Craglia & Annoni, 2006; Lipeg &

Modrijan, 2010).

Suggestions have been advanced early on regarding how developing

countries could initiate their SDI (Bishop et al, 2003) and most started

them towards the turn of the millennium. Meanwhile, SDI assessment

regimes were established in western countries like the SDI Readiness

Index (Fernandez, Lance, Buck, & Onsrud, 2005) and the INSPIRE State of

Play method (Vandenbroucke, Janssen & Van Orshoven, 2008). These methods

have recently been used to assess SDIs in developing countries

particularly in Africa. Makanga and Smit (2010) based their assessment

on the INSPIRE State of Play to assess 29 African countries, whilst

Mawange, Maluku and Siriba (2016) used the SDI Readiness Index over 13

African countries. In both studies it has been revealed that SDI

in Africa continues on an uphill struggle and its developments are

rather slow. Moreover, they stressed that new ways need to be

devised to aid SDI implementation in Africa. The foregoing has motivated

investigation of the phenomenon, leading to the suggested conceptual SDI

partnership framework that outline how the challenge can be addressed.

In an attempt to design a conceptual partnership framework for SDIs

in developing countries, this paper acknowledges that SDIs have been

described as ambiguous. Nonetheless, this study argues that to tackle

issues of ambiguity, a country developing an SDI needs to have a robust

partnerships model to address institutional arrangements, and

relationships of involved communities. The role of partnerships in

SDI development was captured by Rajabifard et al (2008, p14) by saying

that “aspects identified in developing an SDI roadmap include the

vision, the improvements required in terms of national capacity, the

integration of different spatial datasets, the establishment of

partnerships as well as the financial support for an SDI”. We have

endeavoured to describe SDI based on its well-known components and

reconciled them with partnerships in the process proposing a conceptual

partnership framework. The parts of the proposed SDI conceptual

partnership framework will be described in the context of developing

countries’ SDIs assessments and a conclusion drawn.

2. SPATIAL DATA INFRASTRUCTURE AND COMPONENTS

A SDI is a term used to denote a collection of technologies, policies

and institutional arrangements that facilitate the availability and

access of spatial data and services. It provides a basis for spatial

data discovery, evaluation and application for users and providers

within all levels of government, the commercial sector, the non-profit

sector, academia and citizens. According to Lipeg (2010, p2), SDI

development “is an on-going process leading towards spatially enabled

societies and governments”. The SDI concept involves a complex digital

environment that includes a wide range of spatial databases concerned

with standards, institutional arrangements and technologies such as the

World Wide Web (WWW). SDIs are created with efforts and aims of

maximizing the use of spatial information available in many

organizations. SDI components serve as a cornerstone to

establishing consistency and structure in regards to documenting daily

spatial data applications as well as building distributed networks to

facilitate spatial data sharing. They include: a) Technical standards,

b) Access networks, c) Policies, d) Fundamental datasets and services,

e) Institutional arrangements, and f) People (users and producers).

2.1 Technical Standards

The adoption of international standards like the Open Geospatial

Consortium (OGC) specifications helps spatial data and services to be

accessible to a variety of users (Janowicz et al, 2010). In addition,

they make spatial data integration possible over a distributed

environment. However, semantic interoperability still proves to be a

challenge when sharing data in a distributed network. It involves the

structure in which spatial data meaning and terminology are defined. A

step towards semantic interoperability is on the foundation of good data

practice. For example, it is necessary for organizations to standardize

ways in which spatial data is defined and how metadata is structured for

ease of integration with other data from different sources. Technical

standards require partnerships tailored within the context of

technology, engineering and computation viewpoints advanced by Hjelmager

et al (2008).

2.2 Access Networks

The wide adoption of technological advancements like the Internet,

Global Positioning Systems (GPS) units and smart mobile phones makes

them suitable platforms for comprehensive collaborations in SDI

environments (Rajabifard, Feeney and Williamson, 2003). The Internet

provides a primary mechanism where stakeholders can interact using

asynchronous and distributed networks (Vandenbroucke, Crompvoets,

Vancauwenberghe, Dessers, Van Orshoven, 2009). However, developing

countries face problems of slow Internet bandwidth. Spatial data can be

large especially when it involves images. Therefore, ample consideration

and investment has to be made in regard to increasing internet bandwidth

which could be a deterrent to the SDI implementation. In addition, the

widespread use of generalized GPS enabled devices like mobile phones and

hand-held GPS units provide another opportunity where the community

could contribute immensely to the initiative.

2.3 Policies

SDI policies should be backed by the highest office in a country for

the successful implementation of the initiative. For example, the

National Spatial Information Framework (NSIF) of South Africa is a

success story for a developing country, because of the Spatial

Information Bill of 2003, which paved way for the South African Spatial

Data Infrastructure (SASDI) (Spatial Information Infrastructure Bill,

2003 Revised). The NSIF created the necessary buy-in for other

organizations to participate in the initiative and promoted the

development of the country’s SDI, which was later backed by the SDI Act

implemented in 2006. Influence from higher offices has long been

experienced by developed countries. For example, in the US, the

High-Performance Computing Act of 1991, paved way for the National

Information Infrastructure Bill passed in December 1991, by the then

Vice President, Al Gore. Advancement for such initiatives are possible

when comprehensive cooperation, collaboration and coordination are in

place.

2.4 Fundamental Datasets and Services

Fundamental datasets and services are the commodities of SDIs. They

are accessed and processed in a distributed network to generate new

information. Integrating spatial data from a well-structured system like

SDI brings about a wider spectrum of applications as opposed to using

uncoordinated datasets. Furthermore, as noted by Morebodi (2001)

integrated information is of greater value to those who may not have the

expertise to appropriately prepare it for their own use. The user

base has expanded, is now more diverse and directly put pressure on a

wide spectrum of geospatial data management processes, (Elwood, 2008).

For various data sets to be integrated we need to have a robust

geospatial data governance structure mandated to prescribe policies and

standards. The governance structure should be secured through

partnerships of the stakeholders.

2.5 Institutional arrangements

Institutions are platforms on which geospatial data are collected,

collated and constructed into what is known as the SDI. Data is further

shared, exchanged and distributed across a myriad of users. In early

stages, these processes were informal and disjointed as described in

Harvey and Tulloch (2006). These loose arrangements show lack of

proper partnerships between institutions responsible for SDI. In

developing countries this scenario has played itself out for a very long

time and has been responsible for the many challenges experienced in SDI

development. Examples of these can be drawn from the works of

Maphale and Phalagae (2012); Makanga and Smit (2010); and Mawange,

Maluku and Siriba (2016).

2.6 People (users and producers)

People are an important constituency in SDIs. This statement is

relevant now and in future because technology and its advancement keep

on releasing geospatial data sensors for use by everyone. This

scenario has been articulated in Budhathoki, (Chip) Bruce, &

Nedovic-Budic (2008) who acknowledged the role of traditional producers

of SDI but stressed that users are also transcending in to producers due

to the many geospatial sensors and technological advances like

Volunteered Geographic Information (VGI) (Coleman, 2010; Moreri,

Fairbairn, James, 2016). This offers fertile ground for partnerships

where processes can be streamlined to keep SDI developments progressive.

3. PARTNERSHIPS IN SDIs

3.1 What are Partnerships?

Partnerships aim to bring aspirations of sustainability to products

and processes in innovative and collaborative ways. They can be

understood in terms of Mclaughlin (2004) who defined them by saying that

“partnerships represent an important mechanism for bringing government

departments, local authorities and professional groups both within and

between agencies, the private and the voluntary sector, those who

deliver services and those who receive them to work together towards a

common goal”. They occur at various levels ranging from within

organisations, between organisations, locally, nationally and globally.

Partnerships have been found to be very useful by encouraging new

product developments in a number of industries (Dutta and Wiess, 1997;

Ettlie and Pavlou, 2006). The aspect of ‘new product development’

is consistent with SDI and should help us to appreciate why SDIs need

cooperation and partnerships as alluded to by Warnest, Rajabifard &

Williamson (2003). Our appreciation should encourage us to realise the

importance of conceptual framework that can help analyse SDI

adaptability through partnerships.

For organizations in developing countries to have successful

partnerships, they should think and act strategically about their

information needs and the resources needed to deliver to a wider

audience. As noted by Rajabifard et al. (2002) SDIs aim to provide an

environment where stakeholders, both users and producers cooperate in

cost efficient and cost-effective ways to better achieve organizational

goals. Partnerships must not only inform SDI development processes, they

must be functional enough to deliver the benefits associated with it.

The emphasis here is that SDI concepts and partnerships need to be

harmonized to develop national SDIs. Several scholars like Crompvoets et

al. (2008) have summed up SDI concepts as ambiguous and for them to be

understood better, cross-disciplinary research needs to be conducted.

African scholars have also conducted overviews of SDI discourses for a

number of African countries that talks to how various elements that lead

to successful SDI partnerships and development can be exploited

(Morebodi, 2001; Onah, 2009; Makanga and Smit 2010; Maphale and Phalagae

2012; Mawange, Maluku and Siriba 2016).

3.2 The Conceptual SDI Partnership

Looking back at the discussed SDI components it can be deduced that

partnerships can be conceptualised on people and institutional

arrangements. People are crucial for transaction processing and decision

making. As noted, all decisions require data and as it becomes more

volatile, issues of data sharing, security, accuracy and access, make

the need for defined relationships between people and data imminent. In

SDI partnerships, it is necessary to facilitate the role of people and

data governance for decision making and sustainable development of the

initiative. Policies and institutional arrangements in an SDI

environment are concerned with governance structures, data privacy and

security, data sharing and cost recovery issues. They make it possible

for SDIs to meet their objectives and without them, activities like

coordination, cooperation and data sharing cannot be achieved. For SDI

investments to be a success, data services should be offered to a wide

audience to exploit the data usage comprehensively. A healthy and

responsible exploitation of the data would lead to self-sufficiency and

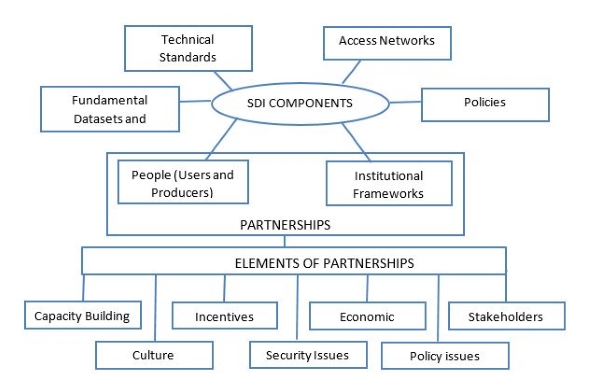

awareness of what others do. In consideration of the SDI components

discussed above a framework is constructed in figure 1 whereby

partnership defines the bedrock for people and institutional

interactions.

Figure 1: Conceptual Partnership for SDIs in

Developing Countries

The illustration in figure 1 is meant to reveal that SDI partnerships

can be premised on two SDI components, namely people and institutional

frameworks as a linkage between other SDI components and various

elements of system development. In that case, figure 1 highlight the

importance of partnerships in building SDIs whereby roles could be

identified in which stakeholders can partake for a successful SDI

initiative.

3.3 Conceptual SDI Partnership Framework Explained

It is necessary for organizations in developing countries to

acknowledge and recognize that there is value added in working with

other institutions. Therefore, figure 1 was constructed by considering

the six main components of SDI and then blocking the people and

institutions together to be the main components on which partnerships

are developable. A number of elements which can directly impact on

partnerships were then identified as shown on figure 1 and they include;

capacity building, culture, incentives, security issues, economic

issues, policy issues and stakeholders. Addressing the above elements

should lead to effective partnerships. Effective partnerships take time,

which requires all those involved to establish appropriate working

frameworks from the start. The structures and processes of the

partnerships evaluation as recommended by World Bank (1998) can be

followed. The partnerships advocated can start from small steps at

operational levels of organisations through management levels within an

organization up to inter-organizational. The operational level could be

involved in data production and dissemination, while the management

level could monitor the operational level as well as for decision making

and creating policies for conducive environments. It is important then

to discuss the elements of the partnership framework within the context

of underlying organisational behaviour, technical and information policy

issues.

3.4 Elements of the Partnership Framework

3.4.1 Capacity Building for SDI

Capacity building in an SDI context refers to improvements in the

ability of all stakeholders to perform appropriate tasks within the

broad set of principles of an SDI initiative. It involves the creation

and development of capacities and capabilities with efforts of solving

problems on spatial information collection, management, sharing and

dissemination. Capacity building does not only involve institutional

assessments and development, it also includes individuals. This is where

the importance of training in creating an enabling environment for SDI

development is realized. Extensive training for a successful SDI is an

essential and significant parameter of a functional partnership

framework. In agreement,

Williamson et al. (2003) stress that training requires a whole new way

of thinking about sharing and exchanging spatial data assets, and

creating optimum solutions that would benefit all partners.

According to Rajabifard (2002) there are different capacity building

factors that are necessary for the success of SDI initiatives. These

factors include technological capacity, human capacity and financial

capacity. Some examples of capacity factors cited by

Rajabifard and Williamson (2004)

include: the level of awareness of stakeholders on values of SDIs; the

state of infrastructure and communications; technological pressures; the

economic and financial stability of each member nation (including the

ability to cover participation expenses); the necessity for long term

investment plans; regional market pressures (the state of regional

markets and proximity to other markets); the availability of resources

(lack of funding, which could be a stimulus for building partnerships,

hence there should be a stable source of funding); and the continued

development of business processes.

Capacity building often focuses on staff development through formal

education and training programs to meet the lack of qualified personnel

in a project in the short term. However,

Rajabifard and Williamson (2004)

argue that capacity measures should be addressed in the wider context of

developing and maintaining institutional infrastructures in a

sustainable way. Moreover, businesses and decision makers should be made

aware of the benefits of having such an infrastructure so that there

could be investment and buy-in.

3.4.2 Culture

In the words of Kok and van Lonoen (2005) “SDI develops gradually”.

This statement need to be embedded into the organizational cultures in

SDIs of developing countries. Leadership of institutions need to be

visionary about this gradual process. Institutional leaders need to

understand that SDIs are better achieved with shared resources than as

individuals working in silos. A culture that lacks the appreciation that

more could be achieved as a collective, is common in developing

countries. Furthermore, the lack of awareness amongst stakeholders on

how they could effectively participate in the initiative is a stumbling

block in many developing countries. In addition, most organizations are

spatial data users and not producers. Users tend to concentrate on their

organizational needs and lack the hindsight that their information when

shared and integrated with others could bring value added products for

the benefit of all. This is supported by Warnest et al (2003) who have

indicated that “implementation of this type of infrastructure will be

facilitated through better understanding and awareness of the

partnerships that support SDI”.

3.4.3 Information Policy Issues

SDIs involve organizations and people sharing fundamental datasets

and services with each other (Rajabifard et al, 2003; Warnest et al,

2003; Hjelmager et al, 2008). However, with the absence of information

policies, procedures and rules that govern and guide

inter-organizational interaction, initiatives like SDIs may fail

terribly. It is necessary for coordinating agencies to clearly address

the issue of policies to all stakeholders involved. This is consistent

with the SDI information viewpoint where policy is recognised as the

starting point and a basis of shaping product specifications (Hjelmager

et al, 2008). Policies should also inform the preparation of guiding

principles for spatial data access, use and pricing models. Furthermore,

they should include legal implications for wrongful handling of

resources in the initiative, to curb abuse and encourage accountability.

These policies if properly implemented, could facilitate easy and

equitable access to spatial data and services. Policies should further

emphasize on maximizing net benefits with less variations on data

pricing and access policies between different stakeholders

(Clarke et al., 2003). In a

nutshell, stakeholders should develop policies that formalize and

legally bind partnerships, clarify participants’ roles and expectations,

such that a conducive SDI development environment is achieved.

3.4.4 Economic factors

Developing countries are known to have budgetary constraints due to

their low economic factors. As such, initiatives like SDIs are best

suited to such environments because a pool of shared resources can

provide more results at minimal cost for organizations involved.

Unfortunately, this has not been the case in most African countries. The

limited resources that developing countries have should be motivation

towards efficient and effective data sharing efforts. In addition, there

should be clear SDI directives and funding mechanisms, as these have

proved to be detrimental in establishing successful initiatives in

western countries like the USA and Canada. Such funding mechanisms can

only be achieved if the limited resources are channelled to where they

are most needed.

Developing countries tend to embrace proprietary software suites more

than free and open source software suites (FOSS). They believe that

proprietary suites have more support compared to FOSS. However,

technological advancements like the Internet, GitHub (a Web-based

development platform for FOSS), and question and answer websites (e.g.

GIS Stack Exchange and Stack Overflow) have made it possible for FOSS

development codes, strategies and documentation to be available to

everyone. Current investments made by developing countries in

proprietary software suites that are pricey and unsustainable, could be

channelled into other resources like improved data collection tools. In

addition, geoprocessing needs and adequate utilization of advanced

software suites in developing countries are very low and these could be

performed sufficiently by FOSS. Hence, the justification that ample

resources are misplaced in tools that do not meet the needs of users.

The adoption of standards in an SDI environment, could enable users and

producers to share spatial data and resources regardless of the software

suite used.

3.4.5 Security Issues

SDIs deal with many stakeholders in a distributed network. They

involve the use of spatial data and resources from a variety of

stakeholders with different needs and purposes like spatial analysis,

optimum route analysis, geoprocessing and other decision-making

activities. Therefore, it is essential that data and services in the

initiative are produced by trusted and properly registered sources.

Enforcing security within the SDI environment can also help attract more

users and producers into the initiative over time. Sufficient security

measures could further increase the integrity of the initiative, thus

attract more organizations to it including late adopters. Other avenues

to increase the integrity of the initiative include: a) upholding

technical standards, b) conducting regular updates of spatial data and

services, c) encouragement of partnerships for value added information,

d) establishing proper monitoring and security measures to ensure that

it is free from virus attacks and abuse, and e) ensuring that only

registered users benefit the most from the initiative.

3.4.6 Incentives

Partnerships are meant to benefit all those involved, hence the need

to identify areas where each participant may benefit from the initiative

is imminent. For all stakeholders involved, a return on investments

study should be conducted for each stakeholder to promote their buy-in.

An example cited by

Borzacchiello and Craglia

(2013), is that organizational structures of each stakeholder could be

inspected and in-depth case studies conducted to gather more information

for better placement into the initiative. However, it should be noted

that initiatives like SDIs may take longer for individual stakeholders

to realize financial benefits, but added value products from utilizing

spatial data from various sources may be achieved. Due to the complex

nature of SDI partnerships,

Rajabifard et al. (2002) suggest

that they should be positioned such that they develop as the SDI

progresses. The authors highlight that users and businesses should drive

the development of SDIs, which in turn will lead to business systems

relying on the infrastructure. Eventually the initiative could become an

infrastructure of successive business systems

(Rajabifard et al., 2002).

3.4.7 Stakeholders

Successful SDI implementations in developed countries have clear

defined roles and responsibilities of stakeholders in their initiatives.

They have a coordinating agency and leading organizations in each

jurisdiction responsible for coordinating efforts in that area. Such an

arrangement helps create an environment of accountability and trust

between stakeholders. Furthermore, it increases stakeholder awareness of

spatial data in the community where proper communication channels can be

used to disseminate it to other stakeholders to reduce duplication of

effort.

Institutions can have their own systems that meet their own needs,

but an infrastructure environment can only be achieved if they are made

interoperable through agreed standards and technical specifications.

This is where the significance and importance of partnerships come into

place. It is necessary for member states to assess the impacts that each

organization’s investment may have in the infrastructure

(Borzacchiello and Craglia,

2013). For example, conducting early impact assessment activities like

that of INSPIRE in 2003-04 where a programme of activities was launched

to practically verify cost and benefit assumptions of the initiative

(Borzacchiello and Craglia, 2013). Rather than being theoretical in all

aspects, some avenues within the infrastructure could be validated in

such a manner at the initial implementation stages.

4.0 A CASE FOR AFRICAN COUNTRIES

Among developing nations, African countries have made their own

efforts towards SDI and some levels of assessment have been carried

based on Inspire State of Play method (Makanga and Smit 2010) and SDI

Readiness Index (Mawange, Maluku and Siriba, 2016). In Makanga and Smit

(2010) where 29 countries were assessed, several elements which are

cornerstones to SDI development were found not to be satisfactory. These

include; coordination, political support, funding and stakeholder

participation. All these elements do bear the hallmarks of SDI

partnerships which if sufficiently promoted and implemented, can produce

positive results. Within a period of six years from Maknga and Smith

assessment a SDI Readiness Index assessment was carried out by Mwange et

al (2016) and the extracted results of the study, presented in tabular

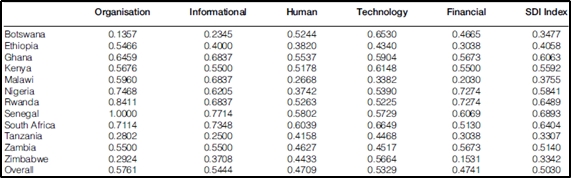

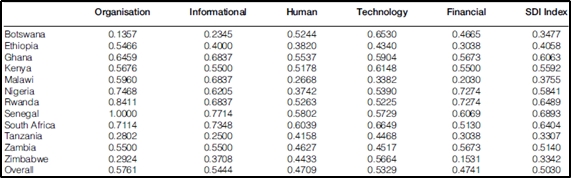

form are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Extract of SDI Readiness Index (Source:

Mwange, Maluku and Siriba 2013)

The SDI readiness Index as depicted in Figure 2 indicate a minimum of

0.33 to a maximum of 0.69. These indices imply that more work needs to

be done and this paper proposes partnerships that should be utilised to

close gaps inhibiting SDI developments in these countries. From the

presented results, organisations and informational elements indices are

very low which could be attributed to weak institutional partnership

arrangements to move SDI forward. The two examples of assessments

carried in Africa by two different researchers using two different

methods suggests strongly that partnerships could be a real problem in

SDI development. Some countries like Botswana, Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi,

Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, South Africa, Tanzania and Zimbabwe are

featuring in both assessments. It is a concern that some of these

countries are still returning readiness indexes which are routinely

described by Mwange et al (2013) as “a lot more work still needs to be

done”.

5. CONCLUSION

Developing countries have in the past struggled to establish SDI

initiatives because of issues that this paper has highlighted in the

conceptual partnership framework outlined. This research argues that SDI

implementations in developing countries can be as successful as those in

developed nations. However, there are some aspects regarding

partnerships that impede developing countries to establish successful

SDI implementations. These failures are attributed to a lack of

understanding and appreciation of how stakeholders can actively

collaborate in partnerships for a successful initiative that benefits

all parties. Therefore, this research has developed a conceptual

framework that highlights an enabling platform where stakeholders can

actively collaborate in the collection, sharing, storage and

dissemination of spatial data. The conceptual framework highlights

issues that developing countries should consider in their efforts to

building functional partnerships for successful SDI implementations. It

is believed that the issues raised and suggestions outlined in this

partnership framework could aid the implementation of a successful

initiative. This paper has put forward a partnerships framework for

consideration in SDI development and made relations to several

assessments carried out on the African continent. Building spatial data

through the power of the functional partnership framework can help

address the following problems; Common geodetic reference framework,

records linking, sharing and data exchange between stakeholders, removal

or reduction of data inconsistencies, cumbersome data presentation and

record keeping, lack of standards in spatial data handling, production

of fit for purpose spatial data products and reduction of

geo-information transaction costs. Future work will further investigate

the proposed conceptual partnerships elements and actually test them in

some African countries by basing then on the preceding mentioned

problems.

REFERENCES

- Bishop, I. D., Escobar, F. J., Karuppannan, S., Suwarnarat, K.,

Williamson, I., Yates, P. M. & Yaqub, H. W. 2000. Spatial Data

Infrastructures for Cities In Developing Countries: Lessons From The

Bangkok Experience. Cities, 171, 85-96.

- Borzacchiello, M. T. & Craglia, W. 2013. Estimating Benefits of

Spatial Data Infrastructures: A Case Study On E-Cadastres.

Computers, Environment and Urban Systems Journal, 41, 276-288.

- Budhathoki, N. M., (Chip) Bruce B., & Nedovic-Budic, Z. 2008.

Reconceptualizing the role of the user of spatial data

infrastructure. GeoJournal, Vol. 72, No. 3/4, pp. 149-160.

- Clarke, D., Hedberg, O. & Watkins, W. 2003. Development of The

Australian Spatial Data Infrastructure, London, Taylor And Francis.

- Coleman, D. 2010. Volunteered Geographic Information in

Spatial Data Infrastructure: An Early Look at Opportunities and

Constraints. GSDI 12 world conference, Singapore.

- Craglia, M. & Annoni, A., 2006. INSPIRE: An Innovative Approach

to the Development of Spatial Data Infrastructures in Europe.

GSDI-9 Conference Proceedings, 6-10 November 2006, Santiago, Chile

Research and Theory in Advancing Spatial Data Infrastructure

Concepts.

- Crompvoets, J., Rajabifard, A., Van Loenen, B. & Tatiana, D. F.

2008. A Multi-View Framework to Assess Spatial Data Infrastructures,

Melbourne, Australia., The Melbourne University Press.

- Dutta, S. and Wiess, A. M. 1997. The Relatioship Between a

Firm's aTechnological Innovativeness and its Pattern of Partnership

Agreements.Managment Science, Vol. 43 No. 3, 343-356.

- Ettlie J. E. and Pavlou, P. A. 2006. Technology-Based New

Product Development Partnerships. Decision Sciences, Volume 37

Number 2, 117-147

- Elwood S. 2008. Grassroots groups as stakeholders in spatial

data infrastructures: challenges and opportunities for local data

development and sharing. International Journal of Geographical

Information Science Vol. 22, No. 1, 71–90.

- Fernandez, T. D., Lance, K., Buck, M. & Onsrud, H. J.

2005. Assessing an Sdi Readiness Index. From Pharaohs To

Geoinformatics, 2005 Cairo, Egypt. Fig Working Week 2005 And Gsdi-8,

1-10.

- Geoconnections, 2013. Spatial Data Infrastructure (SDI) Manual

for The Americas. Available From:

Http://Unstats.Un.Org/Unsd/Geoinfo/Rcc/Docs/Rcca10/E_Conf_103_14_Pcidea_Sdi%20manual_Ing_Final.Pdf

[Accessed 3 Oct 2017]

- Georgiadou, Y., Puri, S. K. & Sahay, S. 2005. Towards a

Potential Research Agenda to Guide the Implementation Of Spatial

Data Infrastructures – A Case Study From India. International

Journal Of Geographical Information Science, 19, 1113-1130.

- Hjelmager J., Moellering H., Delgado T., Cooper A., Rajabifard

A., Rapant P., Danko D., Huet M., Laurent D., Aalders H., Iwaniak

A., Abad P., Düren U. and Martynenko A. (2006). An Initial Formal

Model for Spatial Data Infrastructures. ICA Spatial Data Standards

Commission. International Journal of Geographical Information

Science Volume 22, Issue 11-12. From URL:

DOI:10.1080/13658810801909623.

- Harvey F., & Tulloch D., (2006). Local-Government Data Sharing:

Evaluating the Foundations of Spatial Data Infrastructures.

International Journal of Geographical Information Science Vol. 20,

No. 7, 743–768.

- Janowicz K., Schade S., Arne Bröring A., Keßler C., Maué P., &

Stasch C. (2010). Semantic Enablement for Spatial Data

Infrastructures. Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Transactions in

GIS, 14(2): 111–129.From: doi:

10.1111/j.1467-9671.2010.01186.x [Accessed 29 Sept 2017].

- Kok, B. and van Loenen, B. 2005. How to assess the success

of National Spatial Data Infrastructures? Elsevier, Computers,

Environment and Urban Systems 29 (2005) 699–717.

- Lipeg, B. 2010. Future Challenges for Surveyors in Developing

European and National Societies :- Nmca Point Of View [Online].

Available:

Http://Www.Clge.Eu/Documents/Events/2/18_S_1_En.Pdf [Accessed 14

April 2011].

- Lipeg, B. & Modrijan, D. 2010. NSDI in The Context Of Inspire -

Slovenia’s State Of The Art And Private Sector Challenges.

International Conference Sdi, 2010 Skopje, Macedonia. 1-19.

- McLaughlin, H. (2004). Partnerships: Panencea or Pretence?

Journal of Interprofessional Care, VOL. 18, NO. 2, 104-113.

- Makanga, P. & Smit, J. 2010. A Review of The Status of Spatial

Data Infrastructure Implementation in Africa. South African Computer

Journal, 45, 18–25

- Maphale, L. & Phalaagae, L. (2012). National Spatial Data

Infrastructure in Botswana – An Overview. CSCanada Advances in

Natural Science Vol. 5, No. 4, 2012, pp. 19-27.

DOI:10.3968/j.ans.1715787020120504.1953.

- Morebodi, B. H., 2001. Botswana – Towards a National Geo-Spatial

Data Infrastructure. International Conference on Spatial

Information for Sustainable Development, 2-5 October 2001 2001

Nairobi, Kenya. 1-8.

- Moreri, K., Fairbairn, D. & James, P., 2016. Establishing the

Quality and Credibility of Volunteered Geographic Information in

Land Administration Systems in Developing Countries. GIS Research

UK, 24th Annual Conference, GISRUK, University of Greenwich, London.

- Mueller, H. 2010. Spatial Information Management, an Effective

Tool to Support Sustainable Urban Management. URL:

Http://Www.Isocarp.Net/Data/Case_Studies/1654.Pdf [Accessed 13

Sept 2017].

- Mwange, C., Mulaku, G.C., & Siriba, D.N. 2016. Reviewing the

Status of National Spatial Data Infrastructures in Africa. Survey

Review, Taylor And Francis Group. From Url:

Http://Dx.Doi.Org/10.1080/00396265.2016.1259720 [Acessed 1 Oct

2017].

- Nebert, D. D. 2004. The SDI Cookbook. Global Spatial Data

Infrastructure, 2, 171.

- Onah, C. C. 2009. Spatial Data Infrastructures Model for

Developing Countries – A Case Study of Nigeria. Msc, Westfaelische

Wilhelms Universitaet.

- Rajabifard, A. 2002. Diffusion for Regional Spatial Data

Infrastructures: Particular Reference to Asia and the Pacific. Phd,

The University Of Melbourne.

- Rajabifard, A., Feeny, M. F. & Williamson, I. P. 2002. Future

Directions of SDI Development. International Journal of Applied

Earth Observation and Geoinformation, 4, 11-22.

- Rajabifard A, Feeney M F, and Williamson I. 2003. Spatial Data

Infrastructures: Concept, nature and SDI hierarchy. In Williamson I,

Rajabifard A, and Feeney M F (eds) Developing Spatial Data

Infrastructures: From Concept to Reality. Boca Raton, FL, CRC Press:

17–40

- Rajabifard, A. & Williamson, I. 2004. SDI Development And

Capacity Building. Proceedings of the 7th GSDI Conference, 2-6

February 2004 Bangalore, India.

- Vandenbroucke D., Janssen K., & Van Orshoven, J. 2008. INSPIRE

State of Play: Generic approach to assess the status of NSDIs.

In:J.Crompvoets, J. Rajabifard, B. Van Loenen and T.D.Delgado

Fernandez (Eds). A Multi- view framework to assess Spatial Data

Infrastructures Multi-view framework to assess SDIs pp.11-22. Space

for Geoinformation, Wageningen University and Centre for SDIs and

Land Administration University of Melbourne.

- Vandenbroucke, D., Crompvoets, J., Vancauwenberghe, G., Dessers,

E., & Van Orshoven, J. (2009). A network perspective on spatial data

infrastructures: application to the sub-national SDI of Flanders

(Belgium). Transactions in GIS, 13(s1), 105–122.

- Warnest, M., Rajabifard, A. & Williamson, I. 2003. Understanding

Inter-Organisational Collaboration and Partnerships in the

Development of a National SDI [Online]. Available:

Http://Www.Undp.Org.Cu/Eventos/Espacial/Urisapaper_Warnest.Pdf

[Accessed 24 Sept 2017].

- Williamson, I., Rajabifard, A. & Enemark, S. 2003.

Capacity Building for SDIs. Proceedings of 16th United Nations

Regional Cartographic Conference for Asia and The Pacific, 14-18

July 2003 Okinawa, Japan.

- World Bank 1998. World Bank Partnerships Group, Strategy and

Resource Management In: Bank, P. F. D. P. A. F. T. W. (Ed.)

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Lopang Maphale is a PHD Candidate at the University

of Cape Town in South Africa. He is a Lecturer of geomatics at the

University of Botswana where he is currently on study leave. He is a

Registered Professional Land Surveyor and has MSc in GIS, MBA and

BSc(Hons) in Surveying and Mapping Sciences. He is the former President

of Botswana Surveying and Mapping Association and regular Botswana

representative at FIG. His research in geomatics is in spatial data

infrastructures, modern geospatial technologies, land administration and

geospatial information management in developing economies.

Kealeboga Kaizer Moreri is a PhD student at

Newcastle University, UK. He is a staff development fellow in geomatics

at the University of Botswana where is currently on study leave. He

holds an MSc in Geomatics Engineering from the University of New

Brunswick, Canada and a Bachelor of GIS from the University of South

Australia, Australia. His research interests are in geomatics, spatial

data infrastructure, volunteered geographic information and land

administration.