Article of the Month -

January 2008

|

Developing Cost-effective and Resilient Land Administration Systems in

Latin America

Grenville Barnes; USA

This article

in .pdf-format.

This article

in .pdf-format.

SUMMARY

In this paper I briefly review the wealth of experience in Latin America

with initiatives to strengthen and modernize land administration systems.

The review shows that there is more experience with land administration

projects in this region than in any other. I go on to focus on the question

of costs associated with formalizing property in an attempt to find an

effective means of comparing costs across countries. I approach this by

looking at different ‘levels’ – starting with global budget figures, then

narrowing down to specific components and finally by examining the cost of

individual tasks required to formalize a parcel. A comparative study of

costs in 4 different regions of the world is described together with

preliminary conclusions at the global level. The issue of property

‘deformalization’ is also discussed with respect to transaction costs.

Recognizing that land administration systems, and the economic, social

and natural environments within which they operate, are continually

changing, I introduce Resilience as an appropriate analytical framework

through which to examine changing systems.

Resilience has evolved as a more nuanced framework for understanding the

sustainability of socio-ecological systems. Unlike previous approaches, it

accepts that a system will always be subject to disturbances, whether they

are due to climate (hurricanes), policy and political administration

changes, or demographic shifts due to urbanization or migrant labor markets.

RESUMEN

Esta exposición revisa la gran experiencia en América Latina

sobre las iniciativas para fortalecer y modernizar los sistemas de

administración de tierras. El repaso indica que hay mas experiencia en este

region con pryetos de adminsitracion de tierras que en cualquier otra region

del mundo. El primer parte enfoque en la cuestion de costos vinculado a la

formalización de la propiedad con el motivo de identificar medios aptos para

comparar costos entre diferentes paises. Esta analisis incorpora el estudio

de costos en diferentes niveles – empezando con costos presupuestos

globales, despues enfocando el nivel de componentes individuales y

finalmente se examina los costos para diferentes actividades en el proceso

de formaliza una propiedad. Se discutir un estudio de costos en cuatro

diferentes regiones del mundo y ciertos conclusiones preliminares al nivel

global. Esta discusión incluya tambien la cuestion de ‘deformalización’ de

propiedad con respeto a los costos transaccionales.

Reconozco que sistemas de administración de tierras, y el

ambiente económico, social e ecológico en que el sistema opera, siempre esta

cambiando, se introduzca el Resiliencia como una rama analítica apropiada

para analizar los dinámicos del sistema.

Finalmente, examinaré los sistemas de administración de

tierras a través del lente de ‘resilencia.’ La resilencia se ha desarrollado

como un marco matiz para examinar la sostenabilidad de sistemas

socio-ecologico. A diferencia de previos acercamientos, éste acepta que el

sistema siempre esté sujeto a disturbios, sea a consecuencia del clima

(huracanes), cambios políticos o administrativos, o a desplazamientos

demográficos a causa de la urbanización o migración de mercados laborales.

1. INTRODUCTION

It was appropriate to hold the recent regional FIG conference in Costa

Rica as this country was one of the first countries in the region to

implement what today would be regarded as a land administration project. The

1964 USAID-funded “cadastral survey project” was the pioneer land project in

Central America (Goldstein 1974). The focus of that project was to improve

the property tax system and complete a topographical mapping project which

would provide information for tax, land planning and development purposes.

Similar projects followed soon afterwards in Panama, Nicaragua and

Guatemala, all focused strongly on property taxes, with additional

components addressing natural resource management and land titling in some

cases.

During the 1980s the World Bank began to fund several large land projects

in Latin America and elsewhere. The first two to be completed were the

projects in Thailand and NE Brazil (Holstein 1993). The Thailand “land

titling project,” the ‘mother’ of all land titling projects, started in

1985. This has been a significant project for two reasons. Firstly, it is

regarded as a highly successful project. Secondly, it has been the proving

grounds for the evolutionary theory of land rights (ETLR) which served as

the underlying rationale for many of the subsequent land projects that

followed in the next two decades. Many of the assertions or hypotheses

internal to the ETLR have been empirically proven using the experience of

Thailand (Feder et al 1988). Data was gathered and analyzed to demonstrate

the correlation between titling and access to credit, reduction in property

disputes, facilitation of the land market, and increasing land values (Feder

and Nishio 1996). Based partly on these positive outcomes in Thailand, land

administration projects proliferated throughout the developing world.

Within Latin American the North East Brazil “national land administration

project” was the forerunner of a series of land administration projects in

the region (World Bank 1985). USAID continued to fund land titling projects

throughout the 1980s, including the “land titling projects” in Honduras and

Ecuador (USAID 1985). However, the most successful of the USAID-funded

projects may have been the “Land Titling and Registration Project” in St.

Lucia (USAID 1983). The island-wide land adjudication process was completed

within the originally scheduled time – this by itself may be a unique

achievement amongst land administration projects which invariably stretch

beyond the time frame set out in the project design.

The World Bank has funded land administration projects throughout Latin

America, and even by 1998 a study of World Bank projects revealed that there

were “..115 projects with land-related activities in the Bank’s

portfolio…[and] ..of those, about 40% are in Latin America.” (World Bank

1998, p. 10). Subsequent land administration projects ensued in Bolivia

(1995, 2001), Brazil (1995), Guatemala (1996, 1997), Honduras (2000), Panama

(2000), Nicaragua (2002), Honduras (2003), and El Salvador (2005).

The Inter-American Development Bank has also played a lead role in

funding land administration projects in Latin America and the Caribbean

especially over the past decade – including Trinidad and Tobago (1995),

Nicaragua (1995), Dominican Republic (1997), Belize (1997), Colombia (1997),

Honduras (1998), Jamaica (1999), Costa Rica (2000), Ecuador (2001), Panama

(2002), Brazil (2002), Mexico (2003), Bolivia (2003), Paraguay (2003), and

the Bahamas (2004).

While this is not a complete list of projects it does illustrate the huge

amount of investment that has gone into land administration and property

formalization and therefore the wealth of experience in the region. In the

following section of this paper I bring this experience to bear on certain

key land administration issues, namely the question of costs.

2. COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF COSTS

While significant resources have been invested by the donor community in

modernizing land administration infrastructure around the globe, there has

been little systematic discussion and documentation of actual costs. Better

understanding of the underlying issues and the trade-offs involved in

choosing among different technical, legal and institutional options of

providing land administration services is needed. Even though the World

Bank, IDB and other donors have long supported titling interventions all

over the world, surprisingly little is known about the actual costs of such

interventions, both in terms of project implementation and comparative

transaction costs once the new systems are in place. Until recently, little

effort has been made to disaggregate costs into the specific activities

required to formalize a piece of land.

In reviewing previous studies that dealt with costs, there are several

worth mentioning. In 1985 Janice Bernstein at the World Bank documented a

study she carried out entitled “The costs of land information systems.”

(Bernstein 1985) She compiled information on the topic through “a review of

the literature and illustrative programs as well as discussion with experts

in the field…” (p. 5) She concluded early on that “..there is a great need

for coordinated research among international organizations and training

institutions focusing on the economics of land information..” (p. 11) The

report focused largely on the potential for lowering the cost of cadastral

surveys through inertial surveying and GPS, which were just becoming

operational at that time. It also focused on methods for estimating the cost

of photogrammetric mapping. A fully operational GPS/GNSS system, the higher

precision of today’s satellite imagery, and airborne GPS have essentially

reduced the value of this information to one of historical interest. The

study also contributes little towards the development of a comparative

methodology.

Two years later in 1987 a symposium entitled “The Economics of Land

Information” was held in Baltimore, MD, under the auspices of the Institute

of Land Information (ILI 1987). This issue was topical in the US at that

time as GIS was becoming mainstream and county offices were in the process

of digitizing their land information. Approaches discussed at the ILI and

other forums at that time included: (i) an avoided cost approach, where

benefits are construed as the avoidance of downstream costs by making

upstream (often public) investments in, for example, geodetic infrastructure1

– creating the information now means that it does not have to be repeated at

a later time; (ii) a ‘use and value’ approach whereby benefits are gauged

relative to frequency of use – information that is used more often has more

value even though it may have cost the same to produce. The ‘avoided cost’

approach may have some value, but it focuses more on future costs than more

defensible present or past costs. However, both approaches are not that

useful for developing a comparative methodology as they focus more on

benefits than costs.

Other cross-country studies include work done by Dale and McLaughlin

(1988) and Holstein (1993). Their breakdown of costs by activity is compared

with that given by Bernstein (1985) in Table I below.

TABLE I. Percentage Distribution of Costs by

Activity

|

Source |

Mapping |

Adjudication |

Surveying |

Registration |

Institutional

Strengthening |

|

Bernstein2 |

38% |

29%3 |

|

6%4 |

13% |

|

Dale/McLaughlin |

20-25 % |

30-50 % |

20-25% |

10-15% |

|

Holstein |

24% |

18% |

22% |

23% |

13% |

1 See Epstein

and Duchesneau 1984

2

Based on the NE Brazil Project Costs. Other components included

Support for Land Restructuring” (9%), Project Administration (4%)

and Studies (1%)

3 Land Tenure Identification

4

Cadastre Implementation and Titling

None of these three studies provide a robust comparative analysis

methodology, although they do suggest focusing on activities such as

mapping, adjudication, surveying, etc. Even this can be problematic as

surveying may sometimes be included as a sub-component of adjudication (Dale

and McLaughlin 1990).

Gross unit costs are typically used to compare costs across different

projects, without taking into account the significantly different contexts

and approaches. As a result, cadastral and land registration interventions

are often viewed as expensive activities that do not generate sufficient

benefits to justify their costs. Furthermore, no systematic template exists

for collecting data across different countries. The cost issue came to a

head in a 2001 e-conference on “Lessons Learned in Land Administration”

organized by the World Bank (Deininger 2003; Barnes 2003). One participant

shared information on the Peruvian Titling Project (PETT) which had reduced

the cost of formalizing a parcel to approximately $47 per parcel. In

response to this, another participant countered that in Eastern Europe they

were titling at the cost of $1.05 per parcel! Either these two participants

were talking about two completely different processes and products or else

the contextual setting of these two cases was incomparably different.

Clearly there was a need to ‘unpack’ these numbers and develop a framework

for comparing the same process or product.

Following this conference we developed a template of questions and tables

that could be administered at the country level. We approached this by

identifying costs at three different levels – starting from global project

figures and then considering costs at the level of project components, and

finally examining specific costs entailed in converting a parcel of land

into a formal registered property. We also recognized the need to

contextualize these studies so that the cost figures could be considered

against the specific context within which the project was being implemented.

Subsequently, the template was expanded to include an analysis of the

effectiveness of the land administration system. This ‘template’ was then

applied in seventeen countries in four different regions - Latin America and

the Caribbean (El Salvador, Peru, Bolivia, Trinidad and Tobago), E. Europe

and Central Asia (Armenia, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Latvia), Asia (Indonesia,

Karnataka, Philippines, Thailand) and Africa (Ghana, Mozambique, Namibia,

South Africa, Uganda). Subsequently, four regional reports were prepared

that summarized the country-level reports (Barnes 2002; Adlington 2002; Land

Equity 2003; Augustinus 2003). Finally a global report was prepared

comparing all countries across the four regions (Land Equity 2007).

Instead of drawing on the general data for the global comparison, I have

widened the LAC scope by considering 11 projects within the region. The data

are drawn from the many project documents I have in my own library as well

as others which are listed on the LandNet Americas portal.5

TABLE

II.

Global Comparison of per parcel Costs - Total Project Costs/Total Parcels

6

|

Project |

Total Budget

US$M |

# Parcels |

Dates |

$/parcel |

Area (MHa) |

$/ha |

|

Peru (PETT1) |

36.5 |

1,000,000 |

1997-2002 |

37 |

na |

na |

|

El Salvador

|

70 |

1,700,000 |

1996-2005 |

41 |

1.9 |

37 |

|

Peru (PETT2) |

46.7 |

170,000 |

2003-2007 |

62 |

3.6 |

13 |

|

Costa Rica (IDB) |

92 |

520,000 |

2002-2007 |

177 |

na |

na |

|

Bolivia (PNAT) |

28 |

10,000 |

1995-2003 |

2800 |

3.7 |

8 |

|

Bolivia (St.

Cruz) |

15 |

140,000 |

2006-2010 |

107 |

na |

na |

|

Ecuador (PRAT) |

16 |

135,000 |

2003-2007 |

119 |

0.6 |

27 |

|

Nicaragua

(PRODEP) |

2.4 |

90,000 |

2003-2010 |

27 |

1.4 |

2 |

|

Belize (LMP) |

8.9 |

40,000 |

2003-2006 |

223 |

na |

na |

|

Panama (LARP-IDB) |

72.3 |

120,000 |

2003-2008 |

603 |

0.75 |

96 |

|

Panama (ProNAT) |

47.9 |

80,000 |

2001-2007 |

599 |

1.1 |

44 |

|

Average |

40 |

420,000 |

|

436 |

1.9 |

21 |

|

Average (without

PNAT) |

41 |

|

|

200 |

|

|

|

This kind of comparison is of minimal use partly because

it assumes that the total budget can be associated with the number of

parcels that are either titled or regularized in some way. Costs associated

with legal reform, institutional strengthening, equipment purchases, etc.

are examples of costs that have no relation to parcels, but are still

included in the comparative figures given in Table I. Although the parcel is

the unit of choice when assessing the extent and cost of surveying and

regularization, its cross-scalar nature produces unwelcome complexities. A

‘parcel’ may include any of the following tenure units:

-

small urban lots (e.g. 20m x 30m)

-

peri-urban lots

-

small agricultural parcels (minifundias)

-

medium rural parcels

-

large rural parcels

-

large communally-held parcels (e.g. indigenous

communities)

The scale of a parcel may therefore vary from a small

urban lot to a communal property that may approximate the size of a

municipality. Additionally, at the project design stage the number of

parcels in a jurisdiction or area is often the weakest data available. The

whole motivation for adjudication and titling stems from the fact that there

is no reliable formal parcel information in the registry or cadastre.

Therefore parcel information may be available at the end of the project, but

during design it can only be inferred through estimating average parcel

sizes or consulting census data.

Costs are also estimated on an area (per hectare) basis?

Using the project documents as a source again, those costs that are

available are shown in Table I. Four out of the eleven projects in Table I

do not list area to be titled or regularized in the project document. In the

remainder, the per hectare costs range from $2/ha in Nicaragua to $96/ha in

Panama with an average of $21/ha. This approach to unit costs suffers from

the same problem as mentioned above – it assumes that the cost per unit area

is uniform, ignoring the fact that the multiple scales of parcels contradict

this especially in the fieldwork component. Those projects that contain

several large parcels, such as indigenous communities, skew the cost per

hectare numbers (such as in Nicaragua). It is therefore necessary to look

deeper than these global figures if we are to effectively compare these

projects. It may be more productive to consider the costs of an average size

parcel.

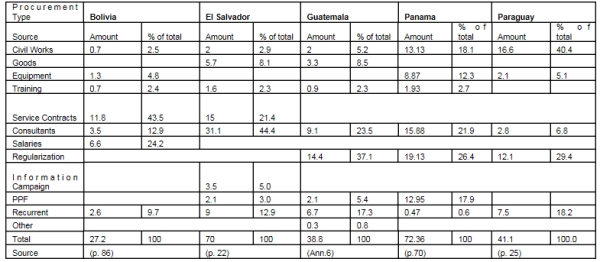

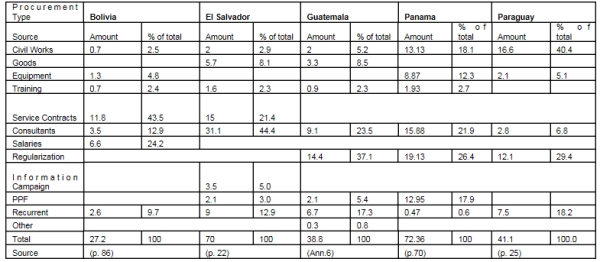

At a more specific level we can examine costs by focusing

on procurement type. Once again, this data is easily available in project

documents, and the results for a small sample of countries is given in Table

III below

TABLE III. Breakdown of Budgeted Costs by Procurement

for Five Countries

FIGURE 1.

Percentage of Budget by Procurement Method

Figure 1 shows that two crucial elements underlying the

success of land administration initiatives – training and

information/communication – rank last in terms of “procurement type.”

However, it is risky to draw any conclusions from these data partly because

several categories in Figure 1 overlap. Training, for example, may be

treated under a separate category in some projects, while in others it will

be included under institutional strengthening. Adding to the complexity of

comparative costs are differences in technologies, variations in

implementation strategies (in-country or through international bid), and

differences in the quality of existing cadastral and registration data,

access and boundary complexity.

Finally, the third level that we examined in the

comparative cost study was the cost for each task required to convert a

parcel from informality into a fully registered property (see Table IV).

TABLE IV Breakdown of Costs to Formalize a Parcel (Land Equity 2007, p.

94)

The number of gaps in the above table shows either that

countries are using different approaches that do not include all of the 19

tasks listed in Table IV above and/or costs are not always reported at this

fine a resolution. It is also important to distinguish between urban and

rural as the Peruvian case indicates rural parcels can cost almost five

times as much as urban parcels.

Looking through even a finer lens at a single cost

sub-component – cadastral survey (#7 in Table IV) – reveals the extent to

which cost can vary at this micro level. Cadastral survey costs for a single

parcel can vary considerably depending largely on four factors: the quality

and scope of the recorded cadastral information, the nature of the terrain,

land value, cadastral evidence (e.g. original monuments/markers, fences)

encountered in the field. In Figure 2 below I have related how these factors

combine to either increase or decrease the survey costs.

FIGURE 2. Four Factors affecting

Cadastral Survey Costs

If land

adjudication (saneamiento) is to be done systematically (barrido) across an

area then the expectation is that this will generate economies of scale,

thereby dropping the per parcel costs. Furthermore, additional efficiencies

can be gained by using methodologies based on GPS which, unlike conventional

approaches, does not require line of sight between all surveyed points. To

what extent do these two factors – economies of scale and the use of GPS –

reduce the survey costs. We were faced with this question in designing the

IDB land administration project in Belize in the mid-1990s. At that time

private surveyors estimated their survey fees on the basis of this simple

formula: US$200 √ area of parcel in acres. In other words, the survey fees

for a parcel of 20 acres would be approximately $900.

Drawing on the experience of the South African cadastral surveying system,

which for more than 60 years had a tariff of fees that incorporated a factor

to account for increasing economies of scale as more parcels were surveyed,

the following figures can be computed in the context of Belize.

TABLE V. Cadastral Survey Fee Structure

accounting for Economies of Scale

|

Number of

Parcels |

Scale Factor |

Factor applied

to Belize Survey Costs7

|

|

1 |

1 |

$900 |

|

2 |

0.7 |

630 |

|

3 |

0.6 |

540 |

|

4 |

0.5 |

450 |

|

5 |

0.4 |

360 |

|

10 |

0.4 |

360 |

|

20 |

0.3 |

270 |

|

100 |

0.3 |

270 |

|

200 |

0.2 |

180 |

|

400 |

0.2 |

180 |

|

1000 |

0.2 |

180 |

7

Assuming an average cost of

US$900 for an individual 20 acre parcel

The scaling factors therefore bring the per parcel costs down to

$180 per parcel assuming that a surveyor is contracted to survey at

least 200 parcels. In addition to these economies of scale,

efficiencies through the use of GPS were estimated to further reduce

the measurement and mapping time by a factor of four. We therefore

concluded that the combination of scale economies and technological

efficiency could reduce the per parcel costs down to as little as

$90 per parcel (Barnes 1995).

Given the large number of variables in just the cadastral

surveying, adjudication, land titling and land registration costs

for formalizing a parcel of land, it is not surprising that we are

faced with an “apples and oranges” type of comparison of costs. I

have just considered initial registration costs in this section, but

there are other costs – especially those relating to subsequent

transactions – that may be even more crucial to the success and

sustainability of a land administration system.

3. TRANSACTION COSTS

Informality results when landholders perceive that the costs and

benefits of the formal system do not match those of the informal

system. In other words, landholders who believe that the costs of

formalizing transactions outweigh the perceived benefits that flow

from such formalization will conduct their transactions outside the

formal system. This is particularly true when informal transaction

costs are further reduced because the parties to the transaction are

members of the same family.

Douglass North’s work on transaction costs, property rights and

institutions has perhaps been the most influential work in terms of

providing a comprehensive approach towards analyzing this area.

North distinguishes between transformation and transaction costs:

The total costs of production consist of the resource inputs of

land, labor and capital involved both in transforming the physical

attributes of a good … and in transacting – defining, protecting and

enforcing the property rights to goods.. (North 1990, p. 28)

When entering into a transaction, such as purchasing a parcel of

land, costs are incurred in the search for information about the

land (quality, value, history, etc.) and the seller’s valid claim to

the land (title, transaction history, third-party claims, etc.). As

North explains:

The costliness of information is the key to the costs of

transacting, which consists of the costs of measuring the valuable

attributes of what is being exchanged and the costs of protecting

rights and policing and enforcing agreements. (p.27)

I

believe that high transaction costs following subsidized titling

efforts are causing substantial ‘de-formalization’ of titled

property. Based on research in St. Lucia and key informant

interviews in the field in numerous countries, we have observed a

tendency for titleholders not to register transactions after they

have received title. Our research in St. Lucia revealed that

approximately 28% of the register was out of date some two decades

after an island-wide titling project, mainly due to informal

generational transfers within families (Griffith-Charles 2004;

Barnes and Griffith-Charles 2006). We believe that the situation in

many other countries will be substantially worse than this.

Comparing the de facto and the de jure situation of land parcels

is also problematic. Collecting de jure data may simply entail a

visit to the registry to extract data on the formal situation.

However, even though most registries in Latin America are ‘registros

publicos’ they most often restrict public access. Access to property

registries may be limited only to those individuals with a valid

interest in a transaction. There is often a fear that documents will

be defiled unless they are handled by competent public officials. On

the other hand, if one does gain entry into the registry large

amounts of data on transactions can be obtained in a relatively

short period of time. Not so with de facto data. This requires more

research and a well-designed sampling strategy that allows

researchers to not only select a representative sample of the total

parcel population but also to be able to link that parcel with the

relevant information in the registry and/or cadastre. Without

reliable geographic information for the registered parcels this can

become extremely challenging.

We can also conclude that institutional differences amongst

countries, including rapid changes in political administration,

levels of decentralization, etc all need to be contemplated when

examining costs. The recent focus on land for the poor also raises

the issue of affordability. We currently do not have a good idea of

what poorer landholders can afford to pay for formalizing subsequent

transactions. Finally, in order to come to grips with land

administration dynamics we need to understand the processes of

change that are occurring in the surrounding environment, in the

landholding population and in the infrastructure and services that

meld together the social-ecological system. Resilience has emerged

as a useful approach towards understanding system change.

4. A RESILIENCE APPROACH

Phenomena such as global warming, increases in natural disasters

such as hurricanes and unpredictable market dynamics remind us daily

that our planet is a highly complex system. Through drawing

disciplinary boundaries – defining social sciences, natural

sciences, etc. - we have in effect parsed our world into more

manageable pieces. However, in the process we have disassociated

social systems from ecological systems and made it more difficult to

understand complex human-environmental interactions.

Over the past decade ecologists and others have defined a

resilience approach to study complex dynamic human-environment

interactions (see, for example, Gunderson and Holling 2002;

Carpenter et al 2004; Anderies et al 2006; Walker and Salt 2006).

Resilience “stresses the importance of assuming change and

explaining stability, instead of assuming stability and explaining

change.” (Folke et al 2003, p. 352) A resilience approach recognizes

that there is no single stable state in a social-ecological system

(SES), but that the system is exposed to different ‘shocks’ that

challenge its fundamental identity and make it dynamic. A resilient

system is able to absorb shocks and adapt without changing its

fundamental structure and function (Gunderson and Holling 2002).

Shocks may be stochastic (e.g. tsunami, land policy reform, major

macro-economic changes), cyclical (flooding), or occur at different

temporal scales – decadal (e.g. drought), annual (e.g. hurricanes,

labor migration) or at smaller time scales.

Through funding from the National Science Foundation, we are

investigating the resilience of social-ecological systems in the SW

Amazon. We focus on connectivity as the primary agent of change,

specifically the trans-oceanic highway that is being paved and will

eventually link the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. The highway will

radically change the connectivity in the region of our research,

which includes the states/departments of Made de Dios (Peru), Acre

(Brazil), and Pando (Bolivia) and is commonly known as the MAP

region. We hypothesize that resilience will increase as connectivity

improves; however, at some level of connectivity it will begin to

become less resilient due to its over-connectedness and consequent

over-dependence on external factors. In short, a graph of resilience

(Y axis) and Connectivity (X axis) will reveal an inverted U shape.

One of the many challenges of operationalizing resilience

analyses is defining what constitutes the ‘fundamental structure and

function’ of a system. In our own research at the University of

Florida we have attempted to do this by examining social, ecological

and social-ecological measures of this identity. Within the context

of land tenure this may be construed as the land administration

framework and the decisionmaking with respect to land and its

associated resources. What does it mean to focus on change within a

land administration system? At a basic level, cadastral and

registration systems are constantly changing as the land market

operates and property is sold and new parcels are created through

subdivision. All successful land administration systems should be

designed to accommodate this constant change, otherwise they will

quickly become out of date. This suggests that the focus in land

administration should be on those parcels that are undergoing the

most change (parcels changing hands or being subdivided) or which

may be susceptible to change (parcels on the frontier). There is one

change that we know will occur in all systems and that is the

eventual death of the landholders. The mechanism for dealing with

this change, namely inheritance, is presenting a key challenge to

the maintenance of land administration systems in the developing

world.

Resilience is best measured when a system has been subjected to

some shock which challenges its continued existence. Extreme shocks

that impact land administration may include natural disasters (e.g.

hurricanes, floods) or anthropogenic fire. A resilient land

administration system is one that can most quickly return to

‘normal’ operation after a shock. If the shock pushes the system

beyond a certain threshold, it will “flip” into a fundamentally

different system. Within the Amazon region, for example, we can

observe indigenous forest areas flipping into treeless ranches which

are composed of entirely different structures (owners, resources)

and processes (land uses). Within the land administration context

this may not be as dramatic, with, for example, a flip from

registration of deeds to registration of title.

There is a recent but growing interest in the resilience of land

administration systems in the face of natural disasters such as

hurricanes and tsunamis. UN Habitat and others are realizing that

the resilience of land administration system and how it is governed

play a key role in recovery and reconstruction efforts following

natural disasters. The resilience framework is highly appropriate

for trying to not only understand the role that land administration

systems have played in past disasters, but more importantly how we

can strengthen these systems to better support recovery and

reconstruction in future disasters.

REFERENCES

-

Adlington, G. (2002).

Comparative Analysis of Land Administration Systems - ECA Regional

Paper. Unpublished. 21p.

-

Anderies, J., B.Walker, and A. Kinzig (2006).

“Fifteen weddings and a funeral.” Ecology and Society, 11(1): 21

-

Augustinus, C. (2003).

Comparative Analysis of Land Administration Systems - Africa Regional

Paper. Unpublished. 26p.

-

Barnes, G. (1995). “An

Assessment of Land Tenure and Land Administration in Belize.”

Unpublished Report, 55p.

-

Barnes, G. (2002).

Comparative Analysis of Land Administration Systems - Latin America and

the Caribbean Regional Paper, Unpublished. 18p.

-

Barnes, G. (2003).

“Lessons learned: An evaluation of land administration initiatives in

Latin America over the past two decades.” Land Use Policy

Journal, Vol. 20/4, pp. 367-374

-

Barnes, G. and C.

Griffith-Charles (2006). "Assessing the Formal Land Market and

Deformalization of Property in St Lucia." Land Use Policy Journal

-

Bernstein, J. (1983). The

costs of land information systems. Water Supply and Urban Development

Department, World Bank.

-

Carpenter, S., B. Walker,

J. Anderies and N. Abel (2004). “From Metaphor to Measurement:

Resilience of What to What? Ecosystems, 4: 765-781

-

Deininger, K. (2003).

Land Policies for Growth and Poverty Reduction. World Bank Policy

Research Report, World Bank and Oxford University Press, Washington,

D.C.

-

Dale, P. and J.

McLaughlin (1988). Land Information Management. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

-

Epstein, E. and T.

Duchesneau (1984). The Use and Value of a Geodetic Reference System.

Rockville, Maryland: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration,

National Geodetic Information Center.

-

Feder, G., T. Onchan, Y.

Chalamnong and C. Hongladarom (1988). Land Policies and Farm

Productivity in Thailand. World Bank Research Publication, Johns Hopkins

University Press, Baltimore.

-

Feder, G. and A. Nishio

(1996). “The Benefits of Land Registration and Titling: Economic and

Social Perspectives.” Paper presented at International Conference of

Land Tenure and Administration, Orlando, FL, Nov 12-14.

-

Folke C., J. Colding, and

F Berkes. (2003). Synthesis: building resilience and adaptive

-

capacity in

social-ecological systems. In Navigating social-ecological systems:

-

building resilience for

complexity and change (F. Berkes, J. Colding and C. Folke, eds.),

Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K. pp. 352-387

-

Gunderson, L. and C.

Holling (2002). Panarchy: understanding transformations in human and

natural systems. Island Press, Washington, D.C., USA.

-

Goldstein, B. (1974).

Inter-Country Evaluation of Cadastral Programs – Costa Rica, Guatemala,

Nicaragua, Panama. AID, Bureau for Latin America, Washington, D.C.

-

Holstein, L. (1993).

Review of Bank Experience with Land Titling and Registration.

Unpublished Report, World Bank, Washington, D.C.

-

ILI (1987). The Economics

of Land Information: A Symposium of the Institute of Land Information.

Baltimore, MD. 78p.

-

Land Equity (2003).

Comparative Analysis of Land Administration Systems – Asia Regional

Paper. Unpublished. 16p.

-

Land Equity (2007). Land

Administration Reform: Indicators of Success and Future Challenges.

Agricultural and Rural Development Discussion Paper 37, World Bank,

Washington, D.C.

-

USAID (1983). Caribbean

Regional Project Paper: St. Lucia Agriculture Structural Adjustment.

Project 538-0090. Washington, D.C.: United States Agency for

International Development, International Development Cooperation Agency.

-

USAID (1985). Ecuador

Land Titling Project. Project Paper. USAID, Washington, D.C.

-

Walker, B. and D. Salt

(2006). Resilience Thinking: Sustaining Ecosystems and People in a

Changing World. Island Press, Washington.

-

World Bank (1985). Brazil

National Land Administration Project, North-east Region Land Tenure

Improvement Project. Staff Appraisal Report, World Bank (LAC Region),

Washington, D.C.

-

World Bank (1998).

Guatemala Land Administration Project. Project Appraisal Document

CONTACTS

Greenville Barnes

Associate Professor

University of Florida

406B Reed Lab

Gainesville FL 32611

USA

Tel + 1 352 392 4998

E-mail: gbarnes@ufl.edu