Land consolidation, customary lands, and

Ghana’s Northern Savannah Ecological Zone: An evaluation of the

possibilities and pitfalls

Zaid ABUBAKARI, Netherlands, Paul VAN DER MOLEN,

Netherlands, Rohan M. BENNETT, Netherlands, Elias DANYI KUUSAANA, Ghana

Zaid ABUBAKARI Elias DANYI

KUUSAANA Rohan M. BENNETT

1)

This paper was presented at the International Symposium on Land

Consolidation and Land Readjustment – held in Apeldoorn, The

Netherlands, 9 – 11 November 2016. The paper demonstrates that Land

Consolidation - as an existing and proven approach - can be used very

well for future challenges - as mitigation of and adaptation to climate

change effects.

SUMMARY

Land fragmentation has been identified to greatly undermine crop

production in many countries. In the case of Ghana’s customary tenure

system, household farmlands are relatively small and are highly

fragmented. Recent agricultural drives, however, have focused on farm

level interventions that are ad hoc with short-term benefits. A

sustainable long-term application of land consolidation which

reorganizes farmlands may improve yields, reduce the cost of production

and improve the incomes of farmers. The successful implementation of

land consolidation depends greatly on the suitability of local

conditions with respect to land tenure and land use. However, in Ghana’s

customary lands, the alignment between the requirements for land

consolidation and existing conditions remains unexplored. This study

investigated the feasibility of land consolidation within the customary

tenure by juxtaposing the local conditions of the study areas with the

baseline conditions for land consolidation outlined in literature. Using

both qualitative and spatial data, the study revealed some traits of

convergence and divergence with respect to the baseline conditions in

the study areas. For example, conditions such as the existence of land

fragmentation, suitable topography and soil distribution were fully met.

Conditions such as the existence of a land bank, technical expertise,

and infrastructure and supportive legal frameworks were partially met.

The remaining conditions such as the willingness to participate,

availability of a land information system and favorable land ownership

structure were non-existent. The circumstances surrounding these unmet

conditions are deeply embedded in customs and traditions that hardly

yield to change. Since these conditions are fundamental for land

consolidation, their absence negates the feasibility of land

consolidation under the current tenure system of the study areas.

1. INTRODUCTION

Agricultural productivity depends on a number of factors which vary

in extent across the globe. These include climatic conditions, level of

technological advancement, farming practices and government policies –

including those related to land tenure systems. With respect to the

latter, a land tenure system might promote land fragmentation, which is

known to undermine agricultural productivity (Demetriou et al., 2013b).

Land fragmentation creates disjointed and small farmlands, thus acting

as a disincentive and a hindrance to the development of agriculture

(Manjunatha, Anik, Speelman, & Nuppenau, 2013). This viewpoint is

however debated: (Blarel, et al. 1992) argues in favour of land

fragmentation describing it as a way of reducing risk and easing

seasonal bottlenecks. In Ghana, it is estimated that about 90% of

farming households operate on less than 2 hectares (MoFA-SRID, 2011):

these farmers keep multiple farmlands for the production of a variety of

crops. Land is predominantly owned and controlled by customary

institutions including chiefdoms, families and Tendaamba (Arko-Adjei,

2011). The control and ownership exercised by these institutions is

built on the concept of collective ownership of land which gives every

member the right to use a portion of the communal land. It is generally

believed that an increase in the number of owners creates land

fragmentation (Farley et al., 2012). Asiama (2002) shares the view that

customary tenure arrangements provide members with equal interests in

land which leads to fragmentation of farmlands as they try to allocate

land for the use of every member. Fragmentation is also linked to

inheritance(Demetriou et al., 2013b; Niroula and Thapa, 2005) as the

continual intergenerational devolution of land from parents to children

increases ownership creates common property which lead to both ownership

and use fragmentation.

For cases like Ghana, if farmland fragmentation is accepted as a

problem, responses will likely depend on innovative approaches such as

land consolidation. Land consolidation is the process of re-allocating

rural land that are considered fragmented (Vitikainen, 2004). It is also

seen as a tool for enhancing agriculture and assisting rural development

(Sklenicka, 2006; Thomas, 2006). The concept of land consolidation has a

history dating back to the Medieval Ages in Europe. The current form of

land consolidation practices have evolved in Europe towards the end of

the 19th Century to the beginning of the 20th Century (Vitikainen,

2004). The concept developed and became multidimensional incorporating

emerging issues like environmental management, development of rural

areas (Zhang et al., 2014) and improvement of appropriate infrastructure

(Vitikainen, 2004). Lemmen et al. (2012) indicated that, the initial

mono-functionality of land consolidation was to increase agricultural

production through parcel enhancement; reduction of production cost and

increase in farm efficiency.

Current interventions in the Ghana agricultural sector including the

Food and Agriculture Sector Development Policy (FASDEP I & II) and

strategies like the Growth and Poverty reduction Strategy (GPRS I & II)

provide seemingly good objectives including the improvement of food

security, enhancement of farmers’ income, application of science and

technology, sustainable management of land, and improvement of

institutional coordination (MoFA-SRID, 2011). However, the

implementation of these objectives focus on subsidies and credit access

programmes which are mostly supported by international donor agencies,

and they subsist as long there is continues support. Over the years, the

attention has therefore always been on short to medium term programmes,

with little or no attention on the sustainable application of long-term

strategies such as land consolidation. Land consolidation is

self-supporting and appears more sustainable and does not require

continuous support from either government or donor agencies.

Experiences with land consolidation in countries like the

Netherlands, Germany and Denmark have demonstrated good results for

agricultural output. In these countries private property rights and

state ownership are dominant, however, scientific research is lacking on

the use of land consolidation within the customary tenure environment

where there is communal ownership of land. Ghana, a country dominated by

customary tenure, has not tested land consolidation as an option for

enhancing agricultural development. Having regard to the complexities of

customary tenure such as oral allocation, indeterminate boundaries and

emotional attachment to land, it is unclear if land consolidation will

be feasible. This premise underlies the overarching objective of this

paper: to investigate the feasibility of land consolidation in the

customary areas of the Northern Savannah Ecological Zone (NSEZ) of

Ghana. Specifically, the study enumerates the baseline conditions

required for conventional land consolidation, examines the existing

tenure and land use situation, and compares the baseline conditions to

the context of the study areas. The paper first provides a background on

customary tenure systems in northern Ghana, land fragmentation and the

consolidation nexus. Subsequently, the study methodology, discussion of

results, conclusion, and policy recommendations.

2. CUSTOMARY LAND TENURE SYSTEMS IN GHANA

The concept of customary tenure is multi-dimensional and has been

used synonymously in different contexts with the terms ‘indigenous

tenure’, ‘traditional tenure’ and ‘communal tenure’ by various

researchers (Arko-Adjei, 2011). USAID (2012) describes customary tenure

as the embodiment of rules that govern the access, use and disposition

of land and its resources within a community. Under customary tenure,

land is sometimes seen as a spiritual entity recognised as a divine

heritage in which the spirits of the ancestors are preserved (Asiama,

2002). Elias (1956) viewed land in the customary context as an age-long

entity that connects the past, present and future members of a

community.

In Ghana, customary ownership accounts for about 80% of the total

land (Kasanga & Kotey, 2001). Families and communities (through

stools/skins1), own these lands. Although differences exist amongst

various ethnicities, there is enough commonality to enable a

categorisation of the Ghanaian customary tenure systems into two broad

groups. The first category is land owned by communities that exist as

chiefdoms. In this category there is a centralised political structure

composed of a hierarchy of chiefs headed by a king. The hierarchy

devolves from the king to paramount chiefs, divisional chiefs and

caretaker chiefs (Arko-Adjei, 2011). Under chiefdoms, each hierarchy of

authority has an overriding power over all the smaller chiefs below it.

The second category is land owned by families where the Tendaamba play

an eminent role in the ownership of land and alienation. Family lands

are controlled by family heads, usually the father in a nuclear family

and the oldest elder in an extended family (Godwin & Kyeretwie, 2010).

1 The use of the terms stool and skin represents the symbols of

authority of chiefs in Ghana. Whilst the stool is the symbol of

authority for chiefs in the southern part of Ghana, the skin (of an

animal) is the symbol of authority for chiefs in the northern part.

There is often the tendency in Ghana to refer to the chieftaincy of a

particular area as the stool or skin. There are even verbal forms

created: to enskin, to enstool; and derived nouns: enskinment and

enstoolment.

3. LAND FRAGMENTATION AND LAND CONSOLIDATION NEXUSES

Land fragmentation is defined as the division of single farmlands

into spatially distinct units (Binns, 1950; McPherson, 1982). King and

Burten (1982a) described the manifestation of land fragmentation in two

forms. First, the division of farmlands into units too small for

profitable exploitation, and secondly, the spatial separation of

farmlands belonging to a single farmer/household. Demetriou (2014)

describes land fragmentation as a spatial problem concerned with

farmlands, which are organised poorly in space with reference to their

shape, size and distribution. Van Dijk (2004) categorised land

fragmentation in terms of ownership and land use. Land fragmentation may

be caused by a number of factors, such as population growth and

inheritance (Binns, 1950; McPherson, 1982; Niroula and Thapa, 2005).

The relationship between land fragmentation and agricultural

productivity is opened to debate. Some researchers including Blarel et

al. (1992) argued in their study in Ghana and Rwanda that fragmentation

of farmland is not as inefficient as generally perceived. They supported

this view by arguing in favour of fragmentation as a tool for the

management of risk, seasonal bottlenecks and food insecurity. This view

is also shared by FAO (2012) who advocated for the maintenance of

fragmented farmlands if they result in productive benefits. Monchuk et

al., (2010) in a study in India concluded that the adverse economic

impacts of land fragmentation are somewhat small but provide room for

adaptation for a variety of circumstances. Contrary to this opinion,

(Niroula and Thapa, 2005) viewed land fragmentation as a mark of farm

inefficiency pointing to its ripple effects on distance, size and shape

of farmlands. Manjunatha et al. (2013) explains that land fragmentation

deprives farmers of the benefits of economies of scale. Demetriou et

al., (2013a) also noted that fragmentation is a disincentive to

mechanised large-scale agriculture. In line with this second debate,

land consolidation has been promoted as a long-term strategy to manage

land fragmentation and promote land use efficiency.

Land consolidation is the procedure of re-allocating a rural area

consisting of fragmented agricultural or forest holdings or their parts

(Vitikainen, 2004). It is a tool for improving land cultivation and

assisting rural development (Sklenicka, 2006). The common principle that

underlie most land consolidation projects is the reconstruction of

fragmented and disorganised landholdings (Thapa and Niroula, 2008).

3.1 Baseline conditions required for land consolidation

Certain conditions are required as input for the implementation of

land consolidation. There exist variations as to what these conditions

are and their difference depends on the particular type of land

consolidation, the objective of implementation and the geographical

context within which it is implemented (Vitikainen, 2004). Conditional

requirements that underpin land consolidation are generally similar but

may be fine-tuned to enable tailor-made packages that meet the needs of

society (Van Dijk, 2007). Contrary to earlier research works of Bullard

(2007) and Vitikainen (2004) which focused more on formal legal

framework, Lisec et al. (2014) argued that the conditions for the

implementation of land consolidation should be reflective of both the

formal and informal institutional framework. For land consolidation to

be implemented, land fragmentation of some sort should have been

established within the geographic area in question (FAO, 2012). Some

researchers have pointed to land fragmentation in a number of ways as a

fundamental factor that calls for land consolidation (Bullard, 2007;

Demetriou, 2014; Long, 2014; Van Dijk, 2007). In the design of land

consolidation for central and eastern European countries, FAO (2003)

enumerated some of the conditions for land consolidation to include;

enabling legislation, land information system, land bank, willingness of

participants to consolidate and technical know-how. Other researchers

such as Jansen et al. (2010) categorised the requirements for land

consolidation broadly into legal and institutional requirements.

Land consolidation in many countries is regulated by legislation(s)

(Vitikainen, 2004). The need for the development of land consolidation

regulations was occasioned in the past when it became apparent that

fragmented lands could not be consolidation based on the operations of

the free land market (Van der Molen and Lemmen, 2004). Legislation is

not only meant to address land fragmentation, but also to prevent the

reoccurrence of fragmentation in the future (Bullard, 2007). Most

importantly, the interference with private property rights during land

consolidation requires a legitimate legal backing so as to protect the

rights of landowners and land users. In view of this, land consolidation

legislation amongst other things defines the limit and manner to which

private property rights may be interfered, the category of right holders

that are recognised and can participate in land consolidation (Hong and

Needham, 2007).

Van Dijk (2007) observed that success in land consolidation depends

on the willingness of landowners and land users to participate in the

process. This is especially the case, where there is no element of

compulsion in participation (Louwsma et al., 2014). FAO (2003) indicated

that the willingness of land owners sometimes depend on the proposed

benefits and the terms of cost sharing between central government

agencies, local government, land owners and users.

When stakeholders are willing to participate in land consolidation it

then becomes necessary have to a reliable land information system

(Demetriou et al., 2013a) which provides an inventory of land

ownership/use rights and also acts as a platform for verifying claims

(Sonnenberg, 2002). The reallocation of lands which involves the

exchange, distribution and portioning of land requires detailed land

information that provides ownership rights, property boundary

information, digital topographic data as well as proposed developments

in the project area (Bullard, 2007). As discussed earlier, land

consolidation in recent times, for most parts of the developed world,

incorporates adjoining public works such as construction of roads,

drainage systems and irrigation facilities which makes it even more

relevant to have a sufficient land information system (Demetriou et al.,

2013a).

Another condition for land consolidation is the existence of a land

bank. Damen (2004) sees land banking as the bedrock for successful land

consolidation. Damen described land banking as a means of acquiring and

managing land in rural areas by state organisations for the purpose of

redistribution/leasing with the aim of improving agriculture or in the

general interest of the public. Land banks provide an opportunity for

expansion, shaping of farmlands, and creation of adjoining

infrastructure (Van Dijk, 2007). Land bank increases land mobility and

creates room for a flexible land consolidation design and reallocation

process (Hartvigsen, 2014).

Being a surface activity, land consolidation is affected by

geographical conditions such as topography, soil and water distribution.

Differences in topography and quality of soil affects land reallocation

which is the core of land consolidation (Lemmen et al., 2012;

Sonnenberg, 2002). In hilly and mountainous areas there exist sharp

variations in surface characteristics and creation of regular shapes for

farmlands may be interrupted by natural physical characteristics of the

terrain like hill tops or cliff faces (Demetriou et al., 2012). This is

further supported by Sklenicka (2006) who sees sharp topographic

differences as one of the factors that hinders land consolidation.

Likewise, substantial soil quality heterogeneity inhibits reallocation

of lands compared to a fairly homogenous distribution of soil quality.

The nature of rights, use and ownership of land affects land

reallocation. Modern land consolidation results in change of ownership

rights and registration of new titles in the land register (Lemmen et

al., 2012). The ability of a private landowner to choose to participate

in land reallocation without any ownership constraints is therefore

important. Thus, dual and multiple ownership either at the family or

community level restricts unilateral decision making. This may hinder

the decision of members in exchanging land during reallocation

(Demetriou et al., 2012). Also, implementing land consolidation requires

some technical capacity and infrastructure. It is difficult to wholly

import and implement land consolidation based on the framework of other

countries that have succeeded in its implementation (Thomas, 2006). It

is necessary for countries, which have not yet implemented land

consolidation to adopt and modify the existing examples to meet their

local needs (Van Dijk, 2007). This can only be done based on expert

technical knowledge. Thus, land use planners, land surveyors, estate

valuation surveyors, land administrators, agricultural engineers and

environmentalist are needed for the preparation and execution of the

land consolidation. Based on the knowledge of the local legal framework,

land market conditions and land tenure, experts are can develop a land

consolidation that efficiently meets local needs. Table 1 summarises the

main baseline conditions.

Table 1: Summary of baseline conditions for land consolidation

| Baseline Factor |

Remark |

| Existence of land fragmentation

|

Land consolidation is the cure for land fragmentation. Where there is no

land fragmentation at all, land consolidation may not be useful. |

| Willingness to participate

|

Willingness to participate in land consolidation implies stakeholder

acceptability and consent. Even without unanimous willingness, some

level of it is required for a successful land consolidation. In some

countries compulsion is used to attain full participation. |

| Availability of land information system

|

Land consolidation requires reliable inventory of ownership rights and

boundary information for its implementation. This enhances

re-allocation; which is the core of land consolidation and dispute

curtailment.

Existence of land bank |

| Existence of land bank |

Land banks provide additional land for uneconomic holdings,

infrastructure and as a substitute stock for unwilling participants

|

| Existence of legal framework |

This enables the protection of private property rights by defining the

limits and manner to which such rights can be interfered. |

| Suitable topography and soil distribution |

Uniformity in surface characteristics of land aids land consolidation as

it affords a fair platform for the exchange of farmlands. |

| Technical Expertise and

infrastructure |

To engender fit-for-purpose land

consolidation technical expertise in local land tenure and land

management dynamics and good infrastructure are essential for

success in land consolidation. |

4. METHODOLOGY AND DATA COLLECTION

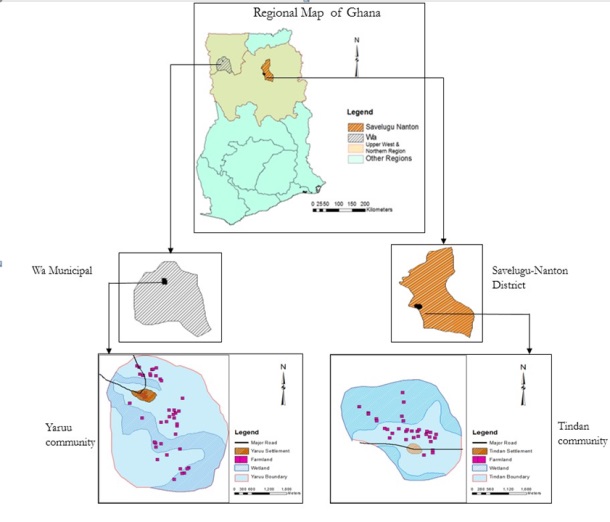

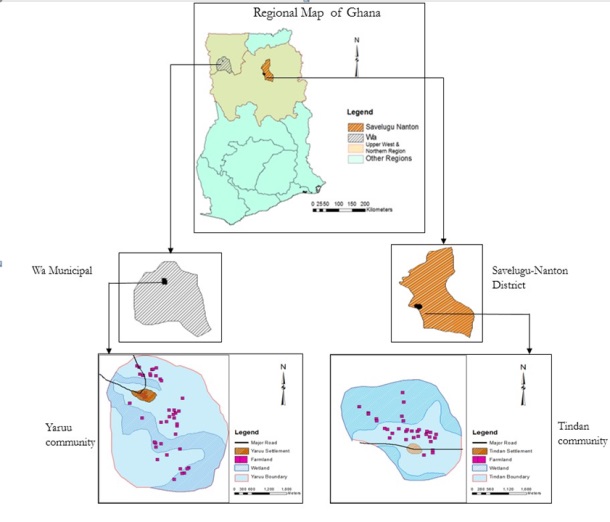

This study was conducted in the Northern Savannah Ecological Zone of

Ghana. Specifically, the Upper West and Northern regions were selected.

This was necessary to represent the two forms of customary land

classification according to Godwin & Kyeretwie (2010). In the Upper West

Region of Ghana, the customary institution was originally built around

the earth priests (Tendaamba) who were literally the owners of the land.

In the case of the Northern region, the customary institution is

organised in chiefdoms headed by kings who manage the land on behalf of

the people. Authority over land devolves from the king through paramount

chiefs to divisional chiefs and caretaker chiefs. Chiefs have the

highest control over land and the level of control exercisable depends

on a chief’s position along the hierarchy. Therefore, to make the study

representative of the customary tenure systems in northern Ghana, two

farming communities were considered; Yaruu, in the Wa Municipality of

the Upper West region, and Tindan in the Savelugu-Nanton district of the

Northern region. These communities were selected because they are

typical farming communities with no formalisation of land rights, no

land commodification, and land uses are dominated by agriculture.

The sample frame for this study comprised 30 farmers with multiple

farmlands from the study areas and 2 customary institutional heads

(Tendaamba and Chief). The institutional heads were purposively sampled

and they assisted in accessing farmers. Primary data was collected

through interviews, focus group discussions and direct observation. This

was supported by multiple sourced secondary data to enrich the

discussions in this paper. The studied farmers were interviewed

regarding the number of farmlands, reasons for the choice of farm

locations, the reasons for having multiple spatially separated

farmlands, the environmental factors that affect the choice of land for

farming and willingness to exchange farmlands. The Tendaana and chief

were interviewed using open-ended questions to examine the land

ownership structure and also their role in and processes of land

allocation. Interviews were conducted with respondents at their homes

and on their farms. Two separate focus group discussions were held in

the two study areas. The focus discussions comprised farmers, chief and

Tendaamba. The focus discussions provided a wider understanding of

complex issues and circumstances that could not be collected from

individual interview sessions. They also provided an opportunity for

participants to express their views and discuss multiple views with

other participants, which gave a clear understanding of the interwoven

dynamics of land ownership and land allocation. For each respondent, we

visited their farmlands and collected data on their locations and

characteristics. The process was made more participatory and interactive

through the use of geo-referenced satellite images downloaded from

Google Earth and geo-referenced using Elshayal Smart GIS software. Soft

copies of the maps were loaded onto a mobile device equipped with a

global positioning system (GPS), which was used to record the geographic

positions of farmlands.

Figure 1: Map of the Study Areas

5. OPPORTUNITIES FOR LAND CONSOLIDATION

5.1 The existence of land fragmentation

Literature highlights land fragmentation as the basis for undertaking

land consolidation especially when it reduces agricultural productivity

(FAO, 2003). The results obtained from this study confirmed the

existence of land fragmentation in terms of land ownership and use in

both study areas. This deduction has been drawn through the

juxtaposition of the findings on household size, farmland size as well

as the number of farmlands per household. On the average, a household

owns three (3) separate farmlands in both study areas. Meanwhile, the

total size of land operated per household ranges from 1- 20 acres

resulting in a size of approximately 1-6acres per farmland, which is an

indication of fragmentation in terms of size. Also, considering the

spatial distribution of discrete farmlands, the average distance between

farmlands of the same owner is approximately 1600m in the case of Yaruu

and approximately 600m in the case of Tindan. Comparing this level of

dispersion to the small size of farmlands gives an idea that farmlands

are somewhat scattered. Similar to the findings of Thapa & Niroula

(2008) in the mountains of Nepal, the study areas exhibited the

tendencies of further fragmentation through the continual inheritance of

farmlands. Considering the household sizes, which range from 3 to 36

persons, it can be reasoned that fragmentation of ownership is inherent

since all male household members have the right of succession. This is

further supported by the fact that most farmers rely on inherence as the

main source of land acquisition. On the contrary, Blarel et al. (1992)

identified farmland fragmentation as a tool for managing seasonal

bottlenecks and food insecurity. In this study, it was revealed that 67%

of the respondents keep multiple farms because of crop diversity and

seasonal risk management. However, 93% of the respondents acknowledged

the problems faced with the operation of fragmented farmlands to

include; the inability to supervise all farms at the same time,

increased travel time and cost and this goes in line with the argument

of Bentley (1987) and Niroula & Thapa (2005). From the foregoing

discussion, it is established that there exist farmland fragmentation,

and this may increase significantly in future.

5.2 Willingness to participate

The success of land consolidation relies on land reallocation which

involves the exchange, portioning and redistribution of farmlands (Van

Dijk, 2007). This interferes with private property rights, and therefore

requires the willingness of landowners and land users to enhance

implementation. In some countries, legislation provides compulsion in

terms of participation since it is difficult to gain full voluntary

agreement. Sometimes voting is conducted in order to determine the level

of willingness of a people when implementing land consolidation. In the

case of Denmark two-thirds majority vote of landowners was solicited for

the execution of land consolidation, while the rest were compelled to

participate. In other countries like Norway, the decision to consolidate

is made by a land consolidation court (Sky, 2002). However, in the study

areas in northern Ghana, consensus is reached through majority community

acceptance and lobbying of opposition groups.

Although Lerman & Cimpoies (2006) identified the success of land

consolidation to be dependent on the willingness of landowners to

exchange farmlands, this study revealed otherwise. Only 40% of the

respondents are willing to exchange farmlands, while 60% of them are

unwilling. Within those who are willing to participate in exchange, only

3 out of a total of 13 are interested in permanent exchange, the rest

are only interested in a short term exchange. In respect of the study

areas, the question arose whether short-term exchanges fit the purpose

of land consolidation? Short-term exchanges undermine the purpose of

land consolidation in northern Ghana in line with the work of Jie-yong,

Yu-fu, & Yan-sui (2012), who emphasize active willingness as key for the

success of land consolidation. From the study, only 10% of the

respondents effectively supported land consolidation through their

willingness to engage in long-term/permanent exchanges. Contrary to this

pattern of response, 93% of the respondents studied are willing to have

their farmlands consolidated if it promises economic benefits.

Reconciling these contrasting responses creates a dilemma. On one hand

farmers are unwilling to exchange their land because of social reasons,

and on the other hand they desire economic gains. Can there ever be a

compromise between these extremes? From the economic point of view, this

situation can be changed if some agricultural infrastructure is provided

and farmers are afforded the opportunity to use single contiguous

farmlands for multiple crops. However, from the social point of view,

strong emotional attachments to land are hard to break. As noted by

Arko-Adjei (2011), the bond between people and land under customary

tenure is only broken under land commercialisation and urbanisation.

Therefore, under the current social climate and remoteness of these

communities, emotional attachment cannot easily be discounted. However,

in the long term the bond may weaken as the communities develop, and

open up opportunities for land commodification. Short-term exchange of

farmlands is inconsistent with modern land consolidation as it will

contradict with permanent change of ownership rights in the land

register (Lemmen et al., 2012).

5.3 Availability of land information system

To successfully undertake land consolidation, there is the need to

have a detail inventory of land ownership, use rights and boundary

information. This provides the basis for verifying ownership claims,

reallocation and settling boundary disagreements. From both study areas,

such land information was non-existent. Land allocation is done with no

written record on ownership, use and boundaries. Boundaries are mostly

demarcated using natural objects. In view of this systemic lapse of land

administration in the area, it may only support private land

consolidation in which participants may exchange lands within their own

agreed terms and criteria. However, comprehensive, simplified and

voluntary land consolidation cannot be done without sufficient land

information. The absence of recorded land information may also call for

the creation of project based land information, however, this is

difficult and time consuming, yet its correctness may not be guaranteed

(Sonnenberg, 2002).

5.4 Existence of a land bank

A land bank creates the opportunity for the expansion of farmlands

and improves adjoining agricultural infrastructure (Damen, 2004).

Assessing land banking from the study areas reveals unique traits. Kotey

(1995) indicated that, allodial title of ownership in chiefdoms resides

in the chief while the subjects have usufructuary interest. This

description fits the Tindan community, which is under the Dagbon

chiefdom. The land belongs to the entire community, while the chief acts

as a trustee. In such a case, all unallocated land within the community

belongs to everybody and is indirectly a land bank that can be used for

farmland expansion and infrastructure creation. Conversely, in the case

of the Yaruu community, all unallocated land is the property of the

Tendaamba. Hence, unallocated land in this situation cannot be

classified as a land bank since it is a private property and entry into

it will constitute trespass. Essentially, the Tendaamba are regarded as

one of the many owners of land though their ownership is the biggest.

Neither the Tendaamba nor individual families have overriding powers

over one another.

5.5 Existence of Legal framework

Legislation as a condition for land consolidation in the context of

the study areas is viewed from the national level since there are no

written laws at the community level, except the norms and customs of the

community. There are no laws on land consolidation in Ghana, and this

form of land reform has never been implemented. However, there exist

pieces of legislations that can be interpreted together to provide the

basis for its implementation. These legislations include the State Lands

Act 1962 (Act 125), which provides regulations for the expropriation of

private property by government; the Administration of Lands Act 1962

(Act 123), which deals with the management and disposition of customary

land and its revenues; the Ghana Highway Act 1997 (Act 540) which

provides regulations for private property interferences in respect of

road construction and the Lands (Statutory Wayleaves) Act 1963 (Act

186), which provides regulations for private property interferences in

respect of public installations and utility works. These pieces of

legislation may serve as the legal basis for the implementation of land

consolidation in the interim, but the extent to which they can

adequately support land consolidation is uncertain. Bearing in mind that

they are not tailor-made for land consolidation, there is a likelihood

of redundancy and inefficiency. These inefficiencies can impede the

realisation of land consolidation. Contrary to having a multiplicity of

legislation, a tailor-made legislation synchronises all the roles of

institutions and stakeholders in an efficient manner. From this point of

view, it can be reasoned that these different legislations may not

provide a solid base for the implementation of land consolidation.

5.6 Suitable topography and soil distribution

Land consolidation is affected by topography and soil quality. Sharp

changes in topography and high level soil heterogeneity limits the land

reallocation process during land consolidation (Lemmen et al., 2012;

Sonnenberg, 2002). The findings indicate that there exist favourable

geographic characteristics. Topographies of both study areas are fairly

flat with a height distribution of 100 - 150 and 300 – 350 meters above

sea level in the Yaruu and Tindan communities respectively. Height

difference in both areas is relatively gentle and is about 50 meters.

Soil on the hand is fairly homogenous and mainly composes of vertisols

and planosols in the Yaruu and Tindan areas respectively. Where there

exist differences in the natural attributes of lands, valuation is used

as a platform for comparison and possible exchange (Sonnenberg, 2002).

It might be based on market valuation (FAO, 2003) or natural yield

potential (Van Dijk, 2003). With respect to the study areas, it stands

to reason that the use of yield potential of soil is most suitable

bearing in mind that, there is no land market in these areas and

agriculture remains the dominant land use.

5.7 Technical expertise and infrastructure

A combination of technical expertise and infrastructure is required

to successfully commence and implement land consolidation. Right from

the conception of the decision to consolidate fragmented farmlands,

expert knowledge in the fields of planning, land surveying, land

administration, financing, engineering and project management is

required for preparatory works and actual execution (Van Dijk, 2007).

Findings from both study areas revealed that local technical expertise

at the community level was lacking. However, human resource is available

and could be harnessed from state institutions which are in charge of

land management, planning and agricultural development. These

institutions include the Land Commission, Town and Country Planning and

the Ministry of Agriculture (MoFA). Experts from these institutions

could be used in the execution of land consolidation in these customary

areas.

6. Conclusion and policy recommendations

In all, the study found out that some of the conditions for land

consolidation were met in a supportive manner. Those conditions, which

were not met, are considered fundamental for land consolidation. The low

level of willingness, absence of a land information system and

unfavourable ownership structure make bleak any opportunity of

implementing land consolidation. Against this background, land

consolidation in its theoretical sense is not feasible in northern

Ghana. However, privately motivated and voluntary land consolidation may

somewhat be supported in a very limited sense. Comparing the suitability

of the two categories of customary tenure systems for land

consolidation, the study found that chiefdoms are more suitable than

communities with Tendaamba. The reasons being that; (1) there is an

overriding authority of the chief over trusted land which can be

exercised to address disagreements (2) there is the opportunity of using

unallocated community land as a land bank. Looking at the trends of

development and transformation of customary tenure under the influence

of urbanisation in Ghana, it is reasonably foreseeable that these

communities will lose their customary characteristics with time. As it

is in many urban areas, there is increased individualisation of

customary land, thus stimulating commercialisation and formalisation.

When this happens, new dynamics of the land market will set in and land

will be held for its economic benefits with no or little emotional

attachment to it and this may open new opportunities for land

consolidation in a much broader context. To this end, the implementation

of land consolidation may not be a very successful intervention to

enhance food security in the customary areas of Northern and Upper West

region of Ghana at this moment.

References

Arko-Adjei, A. (2011). Adapting land administration to the

institutional framework of customary tenure The case of peri-urban Ghana

Adapting land administration to the institutional framework of customary

tenure. University of Twente.

Asiama, S. O. (2002). Comparative Study of Land Administration

Systems: case study, Ghana.

Bentley, J. W. (1987). Economic and ecological approaches to land

fragmantation: in defense of a nuch-maligned phenomenon. Annual Review

of Anthropology, 16, 31–67 CR–Copyright © 1987 Annual Reviews. JOUR.

http://doi.org/10.2307/2155863

Binns, B. O. (1950). The consolidation of fragmented agricultural

holdings. FAO agicultural study 11. Washington DC.

Blarel, B., Hazell, P., Place, F., & Quiggin, J. (1992). The

economics of farm fragmentation: evidence from Ghana and Rwanda. The

World Bank Economic Review, 6(2), 233–254.

Bullard, R. (2007). Land consolidation and rural development. Papers

in Land Management. Anglia Ruskin University, Cambridge.

Damen, J. (2004). Land banking in The Netherlands in the context of

land consolidation. Paper presented at the International Workshop: Land

Banking/Land Funds as an Instrument for Improved Land Management for

CEEC and CIS. Tonder, Denmark.

Demetriou, D. (2014). The development of an integrated planning and

decision support system (IPDSS) for land consolidation. University of

Leeds.

Demetriou, D., See, L., & Stillwell, J. (2013). A spatial genetic

algorithm for automating land partitioning. International Journal of

Geographical Information Science, 27(12), 2391–2409.

http://doi.org/10.1080/13658816.2013.819977

Demetriou, D., Stillwell, J., & See, L. (2012). Land consolidation in

Cyprus: Why is an integrated planning and decision support system

required? Land Use Policy, 29(1), 131–142.

http://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2011.05.012

Demetriou, D., Stillwell, J., & See, L. (2013). A new methodology for

measuring land fragmentation. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems,

39, 71–80.

http://doi.org/10.1016/j.compenvurbsys.2013.02.001

Elias, T. O. (1956). The nature of African customary law -.

Manchester United Press, Manchester-England.

FAO. (2003). The design of land consolidation pilot projects in central

and eastern Europe. FAO Land Tenure Studies (Vol. 6). Rome, Italy.

FAO. (2012). Responsible governance of tenure of land, fisheries and

forests in the context of national food security. Voluntary Guidelines.

Godwin, D., & Kyeretwie, O. (2010). Land tenure in Ghana: making a

case for incorporation of customary law in land administration and areas

of intervention. Retrieved from

http://www.growingforestpartnerships.org/sites/gfp.iiedlist.org/files/docs/ghana/ghana_land_tenure-gfp_project.pdf

Hartvigsen, M. (2014). Land mobility in a central and eastern European

land consolidation context. Nordic Journal of Surveing and Real Estate

Research, 10(1), 23–46.

Hong, Y.-H., & Needham, B. (2007). Analyzing Land Readjustment:

Economics, Law, and Collective Action. Cambridge: Lincoln Institute of

Land Policy.

Jansen, L. J. M., Karatas, M., Küsek, G., Lemmen, C., & Wouters, R.

(2010). The computerised land re-allotment process in Turkey and the

Netherlands in multi-purpose land consolidation Projects. In Proceedings

of the 24th International FIG Congress. Sydney, Australia.

Jie-yong, W., Yu-fu, C., & Yan-sui, L. (2012). Empirical research on

household willingness and its caused factors for land consolidation of

Hollowing village in Huang-Huai-Hai traditional agricultural area.

Sciencia Geographica Sinica, 32(12), 1452–1458. SCIENTIA GEOGRAPHICA

SINICA. Retrieved from

http://geoscien.neigae.ac.cn

Kasanga, K., & Kotey, N. . (2001). Land management in Ghana: building

on tradition and modernity. International Institute for Environment and

Development. London.

King, R., & Burten, S. (1982). Land fragmentation and consolidation

in Cyprus: a descrcriptive evaluation. Agricultural Administration,

11(3), 183–200.

King, R., & Burton, S. (1982). Land fragmentation: notes on a

fundamental rural spatial problem. Progress in Human Geography, 6(4),

475–494.

Kotey, E. N. A. (1995). Land and tree tenure and rural development

forestry in northern Ghana. University of Ghana Law Journal, 19,

102–132. JOUR.

Lemmen, C., Jansen, L. J. M., Rosman, F., & Rosman, F. (2012).

Informational and computational approaches to land consolidation

informational and computational approaches to land consolidation. Rome,

Italy.

Lerman, Z., & Cimpoies, D. (2006). Land consolidation as a factor for

successful development of agriculture in Moldova. In Proceedings of the

96th EAAE seminar on causes and impacts of agricutural structures.

Lisec, A., Primožiè, T., Ferlan, M., Šumrada, R., & Drobne, S.

(2014). Land owners’ perception of land consolidation and their

satisfaction with the results – Slovenian experiences. Land Use Policy,

38, 550–563. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2014.01.003

Long, H. (2014). Land consolidation: An indispensable way of spatial

restructuring in rural China. Journal of Geographical Sciences, 24(2),

211–225.

http://doi.org/10.1007/s11442-014-1083-5

Louwsma, M., Beek, M. V. A. N., & Hoeve, B. (2014). A new approach:

participatory land consolidation. In : Proceedings of the International

FIG Congress (pp. 1–10). Kuala Lumpur-Malaysia.

Manjunatha, A. V., Anik, A. R., Speelman, S., & Nuppenau, E. A.

(2013). Impact of land fragmentation, farm size, land ownership and crop

diversity on profit and efficiency of irrigated farms in India. Land Use

Policy, 31, 397–405.

http://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2012.08.005

McPherson, M. F. (1982). Land fragmentation: a selected literature

review. Development Discussion Paper (No. 141). Havard Institute for

International Development. Havard University.

MoFA-SRID. (2011). Agriculture in Ghana: facts and figures. Retrieved

from

http://mofa.gov.gh/site/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/AGRICULTURE-IN-GHANA-FF-2010.pdf

Monchuk, D., Deininger, K., & Nagarajan, H. (2010). Does land

fragmentation reduce efficiency : Micro evidence from India Klaus

Deininger. Paper prepared for presentation at the Agricultural & Applied

Economics Association 2010 AAEA,CAES, & WAEA Joint Annual Meeting,

Denver, Colorado.

Niroula, G. S., & Thapa, G. B. (2005). Impacts and causes of land

fragmentation, and lessons learned from land consolidation in South

Asia. Land Use Policy, 22(4), 358–372.

http://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2004.10.001

Sklenicka, P. (2006). Applying evaluation criteria for the land

consolidation effect to three contrasting study areas in the Czech

Republic. Land Use Policy, 23(4), 502–510.

http://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2005.03.001

Sky, P. K. (2002). Land consolidation organized in a special court –

experiences from Norway. Paper presented at the international symposium

on land Fragmentation and land consolidation in central and eastern

European countries.

Sonnenberg, J. (2002). Fundamentals of land consolidation as an

instrument to abolish fragmentation of agricultural holdings (pp. 1–12).

Thapa, G. B., & Niroula, G. S. (2008). Alternative options of land

consolidation in the mountains of Nepal: An analysis based on

stakeholders’ opinions. Land Use Policy, 25(3), 338–350.

http://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2007.09.002

Thomas, J. (2006). Attempt on systematization of land consolidation

approaches in Europe. Zeitschrift Fur Geodasie, Geoinformation Und

Landmanagement, 131(3), 156–161.

USAID. (2012). The future of customary tenure: options for policymakers.

Retrieved from

http://usaidlandtenure.net/sites/default/files/USAID_Land_Tenure_2012_Liberia_Course_Module

_1_Future_of_Customary_Tenure.pdf

Van der Molen, P. (editor), & Lemmen, C. H. J. (editor). (2004).

Modern land consolidation : proceedings of a symposium by FIG commission

7, September 10 - 11. GIM International, 19(1).

Van Dijk, T. (2003). Dealing with central European land

fragmentation. A critical assessment on the use of western European

instruments.

Van Dijk, T. (2004). Land consolidation as Central Europe ’ s panacea

reassessed. Paper presented at the symposium on modern land

consolidation (pp. 1–21). Volvic, France. Retrieved from

http://www.fig.net/commission7/france_2004/papers_symp/ts_01_vandijk.pdf

Van Dijk, T. (2007). Complications for traditional land consolidation

in Central Europe. Geoforum, 38(3), 505–511.

http://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2006.11.010

Vitikainen, A. (2004). An Overview of Land Consolidation in Europe.

Nordic Journal of Surveying and Real Estate Research, 1(1), 25–44.

Zhang, Z., Zhao, W., & Gu, X. (2014). Changes resulting from a land

consolidation project (LCP) and its resource–environment effects: A case

study in Tianmen City of Hubei Province, China. Land Use Policy, 40,

74–82.

http://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2013.09.013

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This paper is an excerpt of an earlier publication in Land Use Policy

journal, Volume 54, 2016, pages, 386–398

CONTACTS

Zaid ABUBAKARI

University of Twente,

Faculty of Geo-Information Science and Earth Observation (ITC)

Hengelosestraat 99

7514 AE Enschede,

THE NETHERLANDS

Email: z.abubakari@utwente.nl

Paul VAN DER MOLEN

Professor Emeritus

University of Twente,

Faculty of Geo-Information Science and Earth Observation (ITC)

Hengelosestraat 99

7514 AE Enschede,

THE NETHERLANDS

Email: p.vandermolen-2@utwente.nl

Rohan BENNETT,

Associate Professor

University of Twente,

Faculty of Geo-Information Science and Earth Observation (ITC)

Hengelosestraat 99

7514 AE Enschede,

THE NETHERLANDS

Email: r.m.bennett@utwente.nl

Elias DANYI KUUSAANA

Lecturer

Department of Real Estate and Land Management

University for Development Studies (UDS-Wa Campus)

P.O. Box UPW 3, Wa, Ghana

Email: eliaskuusaana@yahoo.com

|